Some children dream of being astronauts or ballerinas. Laura* wanted to be an entrepreneur. At 23, the Breton woman believes she has realized her dream by becoming a “distributor” of the French version of Herbalife Nutrition, an American company offering food supplements and meal replacements. After being contacted by an unknown person on Instagram, the young woman adopted the brand, which allowed her, she assures us, to “lose 3 kilos of fat and gain 2 of muscle without doing sports”. Since then, she has been praising its merits and, above all, recruiting in her turn: in just over a year, she has converted several dozen people, who in turn have become “distributors” of the brand. “Last month, I received 1,500 euros thanks to my 50 distributors spread over six levels. It’s great!”, She says. These results convinced Laura’s parents, sports coaches, to trust the brand. “Even if it is not very well seen in their sector”, recognizes the young woman.

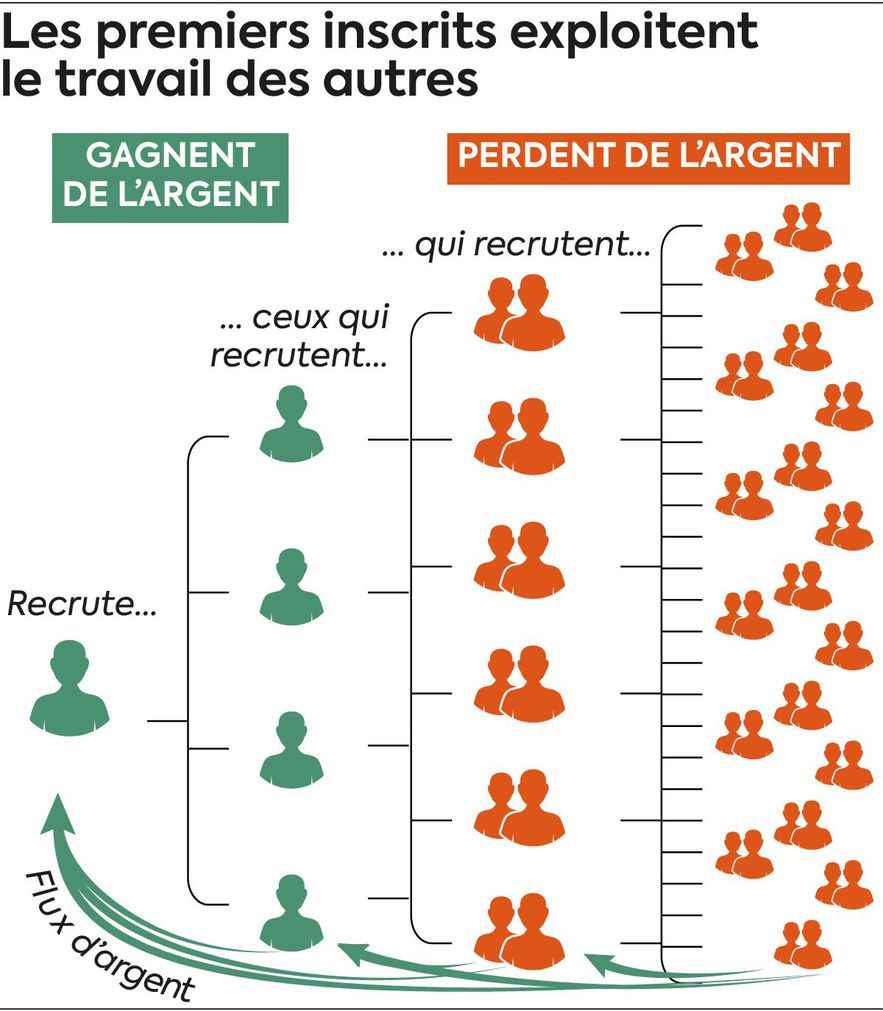

Behind the promises of weight loss and quick money, Herbalife has a dark reputation, tainted by its controversial method of multilevel selling (VMN). Its distributors earn money through their direct sales, while pocketing a percentage of those made by the network of salespeople they have recruited themselves. In theory, the more participants sell and recruit, the greater their earnings. But the fairy tale is often less brilliant.

Renowned in the world of network marketing, the company has been accused of pyramid selling several times. In the United States, in 2016, it even had to pay a $200 million fine to the Federal Trade Commission. “Herbalife Nutrition’s system is not a pyramid system, neither close nor comparable,” Herbalife assures us. But with its guarantees of financial independence and its promises of entry into its “community”, the company illustrates the pitfalls of multilevel marketing. She is not the only one: these companies are called It Works!, Modere, or Jolimoi. Their modus operandi, favored by recruitment on Instagram or TikTok, is increasing among young people, and can sometimes seem at the limit of legality.

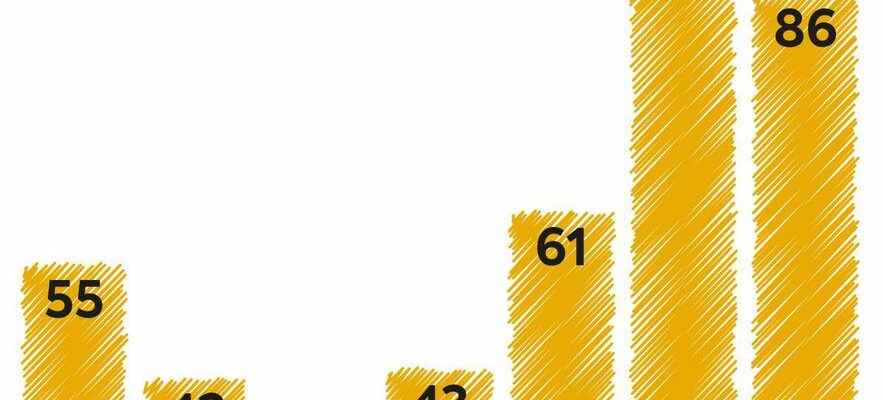

Infographics

© / Dario Ingiusto / L’Express

Snowball effect

Pyramid selling is a scam scheme that gets its name from its shape. At its top, the person behind the scam first recruits the first level of the pyramid – let’s say five investors, who each pay 100 euros. The initiator pockets 500 euros, while the first level of the pyramid receives nothing. To start earning profits, the members must in turn each recruit five new investors – for 20 euros each, in the example used – and so on. With each recruitment, the “upper floors” reap a percentage of the earnings. But when the pyramid can no longer expand, because its members can no longer recruit enough, the system collapses. The lower floors lose the money they invested. These scams can take on gigantic dimensions: in early November, US authorities announced that they had charged four people for their role in a bitcoin pyramid scheme that cost nearly $300 million to 100,000 people around the world.

In France, this “snowball” system is punishable by two years’ imprisonment and a fine of 300,000 euros. Conversely, multi-level selling remains legal: the popular Tupperware brand, for example, uses sponsorship and word-of-mouth to sell its products. Sellers are paid for selling goods, not for recruiting new sellers. “Our distributors are commissioned solely on the basis of the sale of our nutritional products. We do not commission the recruitment (sponsorship) of new distributors or customers”, guarantees us from its side Herbalife. “But many companies practicing pyramid selling hide under the VMN, and claim to remunerate only the sale of their products”, points out Marie Drilhon, vice-president of the National Union of Associations for the Defense of Families and Individuals. victims of sects. It is therefore difficult to determine which companies are honest and which are scams.

“When the promises of earnings relate more to commissions from the sponsorship of new members than to the products sold, be careful, explains Claire Castanet, director of relations with savers at the Autorité des marchés financiers (AMF). If we cannot return only by sponsorship, that you must first pay a subscription or a license, recruit with all your might, and that you are promised rapid enrichment, without effort, without knowledge, you have to go your way.” Beyond the financial losses that a possible scam can cause, the psychological drifts of the VMN itself are worrying. For several years, the VMN phenomenon has also attracted the attention of the Interministerial Mission for Vigilance and the Fight against Sectarian Abuses (Miviludes), which is concerned about a system “particularly present” on social networks since the health crisis, and which would mainly affect young people aged 16 to 25 – in 2020, the organization thus received 120 reports on the subject, double from 2019 and triple from 2018. The scams are today in the peloton of head of reasons for reporting with an economic connotation to Miviludes.

Infographics

© / Dario Ingiusto / L’Express

“Hello to you, young entrepreneur”

“On social networks, if you react to one of their publications, the sellers come to talk to you in private message … And that’s where they manage to get you”, testifies Thierry, founder of several Facebook groups of Help for scam victims. But, in reality, these VMN networks “only benefit the companies that carry them and the ‘independent distributors’ who arrived first”, warns Miviludes. The organization observes that these networks, using the springs of “mental manipulation and gambling addiction”, can sometimes encourage young people “to break with their family environment”, to “leave their studies in favor of a enterprise presenting a high risk of financial loss” or to “spend their savings, their savings or their meager income”. Marie Drilhon knows this phenomenon all too well. Recently, she claims to have received reports from families of “cut off” teenagers, obsessed with their multi-level sales network and their meager results.

“They sell you the dream, and you get into it 100%”, testifies Mathilde *, who worked for more than four months for the Herbalife company. After letting herself be convinced by a classmate who lures her with the promise of easy money, the student then spends whole days convincing her relatives to buy products – whose composition she does not know -, participate in team meetings or recruit other sellers on Snapchat. “We were pushed to sell at least 500 euros of products each month, and to recruit at least five people.” On the weekends, she goes to conventions in “great hotels”, where the most experienced salespeople deliver a series of sales tips and motivational mantras to new hires. But, despite her efforts, Mathilde does not sell. Between its membership, its stocks and the financing of the conventions, it estimates to have lost “600 to 800 euros”, without any return on investment. “And, above all, I missed my year of BTS,” she breathes. After yet another meeting, during which “a big boss” of the company receives her face to face to “hold her to account”, she ends up breaking down. “He put a lot of pressure on me. I understood that something was wrong, and I decided to stop everything.”

Mathilde stopped in time. Not everyone is so lucky. “Some people invest themselves emotionally, give themselves fully to the community functioning encouraged by the brand, and cut themselves off from everything else. In these cases, there is a high risk of sectarian drift”, analyzes Elisabeth Feytit, podcast creator shock meta, specialized in modern beliefs and their drifts. While recruits join dozens of private groups on Telegram or WhatsApp, and are pushed every day to develop their network and their sales, the documentary filmmaker evokes an “escalation of commitment” which can, in the long term, create a certain “dependency and putting the critical mind to sleep”. “There is a whole mythology around success, different statuses to be obtained through work and motivation. You always get more involved, and that is never enough”, she summarizes. Far from the mirages of freedom promised by companies.

*Names have been changed.