More than two years after the appearance of Covid-19, a new epidemic linked to a zoonosis hits Europe: monkey pox. The disease, mainly present in central and western Africa, has spread rapidly across the world in recent weeks. To the point that the World Health Organization (WHO) considers its dissemination “worrying” and will convene a meeting next week to assess whether this virus represents a “public health emergency of international concern”. Less than a week after calling on states to “control the outbreak”, WHO Director General Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus on Tuesday June 14 deemed the spread of the epidemic “unusual”.

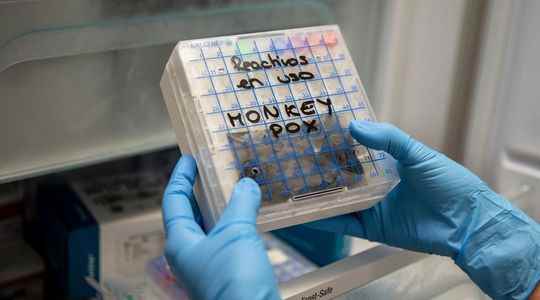

Since early May, more than 1,600 confirmed cases have been reported in 39 countries, including 32 where the disease is not endemic – and where no deaths have yet been recorded. The virus is now present in Europe, Australia, the Middle East, North America and South America. In France, there are currently 91 proven cases, without serious form. But scientists are mobilizing to answer a question: how did this disease spread so quickly on the Old Continent, epicenter of the epidemic with 85% of cases, as well as in America?

From zoonosis to human-to-human transmission

A step back is necessary. Monkey pox – “monkeypox” in English – was discovered in Denmark in 1958 following a generalized eruption on captive crab-eating macaques from Singapore. Hence its name, even if the monkeys would have been infected only during transport by other animals (squirrels or small rodents) vectors of the disease. Quickly, the WHO set up close monitoring of this new disease, which then risked threatening the eradication of human smallpox. Over the years, several epidemics have been recorded around the world in monkeys in captivity. In France, several cases are listed on chimpanzees brought from Sierra Leone in 1968 in an animal facility of the Pasteur Institute. Two years later, in 1970, the first human case was discovered in a baby in the Democratic Republic of Congo. From there, the African continent is hit several times by more or less large epidemics. Since the 2010s, and compared to the 1980s, the number of cases has increased tenfold.

The first human outbreak of non-African monkeypox occurred in 2003 in the United States, where it was imported from Ghana by wild rodents, including Gambian rats. These in turn infected prairie dogs in pet stores. All patients had contact with a sick prairie dog, and there was no human-to-human transmission. Other cases are recorded in Great Britain in 2018, with this particular that a hospital worker was contaminated while cleaning the bedding of a patient. This is the first confirmed case of human-to-human transmission outside of Africa. Four years later, in 2022, monkeypox once again left the African continent – where it has been proliferating for a decade – to conquer Europe, which has become the epicenter of the epidemic.

In France, as elsewhere, a procedure has been put in place to trace the chains of contamination. Thanks to these initial investigations, the scientists were able to establish that the strain circulating in Europe and the United States is the same as that circulating in West Africa. In other words, the least serious with a 1% mortality rate, compared to 5% to 10% for its Central African cousin. Another lesson: the European epidemic probably has a single origin, because similarities in the sequencing have been observed on several samples. The responsiblesWesterners fear that the virus is currently spreading undetected through community transmission, possibly through a new mechanism or pathway. An investigation is still trying to determine where and how the infections are occurring.

A gay pride as a superpropagator

How did the virus arrive in Europe, and when? The WHO estimates that the epidemic on the continent “was certainly underway as early as mid-April”. The first officially recorded case is a Briton who returned on May 4 from Nigeria, a country where monkeypox circulates more than elsewhere. “It is not patient zero, this denier has still not been identified and could have been infected many months ago, tempers virologist Hervé Fleury, researcher at CNRS and professor emeritus at the University of Bordeaux. It’s probably someone who was also infected in West Africa, that’s quite common. On the other hand, what is less common is that this virus, which usually spreads quite badly between humans, circulated very quickly, and without a direct link with an African country or an animal reservoir”. In France, the first patient diagnosed dates back to May 20. He is a 29-year-old man residing in Ile-de-France, with no history of travel to a country where the virus is circulating.

Another disturbing discovery: the virus would circulate mainly within the homosexual community, and in several countries at the same time. Clues lead to a gay pride organized in early May in the Canary Islands, a potential “superpropagator” event. “It’s not where the epidemic started, nuance Hervé Fleury, but a mass gathering where there could have been a lot of contamination”. Other outbreaks of this type have been identified, such as a gay sauna in Madrid at the origin of around forty cases, or a festival in Belgium. Hans Kluge, director of WHO Europe, however warned on Wednesday June 15 against the risks of stigmatization, stressing that “the monkeypox virus is not in itself attached to any specific group”. Especially since, according to a study published in 2020 in the journal Science, human-to-human transmissions had already been observed in several African prisons, with however a fairly short chain of transmission ranging from 1 to 3 individuals. Again, young adult males were most affected.

Beyond the populations affected, other questions remain unanswered: is this disease transmitted sexually? “Researchers are studying this track but there is no proof in this direction at the moment”, assures Hervé Fleury. Another question: has the virus mutated? “Here again, the question arises but there is no evidence to prove it, especially since monkeypox evolves quite little due to its DNA genome – compared to other RNA viruses such as Sars-CoV-2. “, continues the virologist. In Portugal, a team of scientists analyzed the genome of the virus taken from nine patients and discovered small mutations. “The eruption is a little different from that observed in Africa, with many more lesions in the genital sphere”, specifies Pr Arnaud Fontanet, epidemiologist at the Institut Pasteur on France info. Is this the start of a new mode of transmission between humans? Too many unknowns do not yet allow us to confirm this.

Many gray areas

It remains to wonder about the causes of the emergence of this epidemic. The virus has been increasingly present in many African countries for a decade. For Hervé Fleury, this is the result of the cessation of vaccination against smallpox in the early 1980s ordered by the WHO. “The population is no longer immune and therefore more sensitive to an epidemic rebound”, he judges. An opinion shared by India Leclercq, researcher at the Institut Pasteur’s emergency biological intervention unit: “That’s why we find cases more in young people who don’t have been vaccinated against the smallpox virus at all”. “The other explanation for this resurgence is found on the side of these populations more frequently exposed to the animal reservoir”, estimates the researcher, in particular due to globalization, deforestation, cultivation, etc. However, virologist Hervé Fleury is concerned to see a virus such as monkeypox spreading locally in Europe, without cases of importation. “Imagine if a virus like Ebola, with a fatality rate of around 50%, also emerged in Europe. It would be catastrophic! We must therefore understand how monkeypox imposed itself”.

However, monkeypox is not comparable to Covid-19. It is less serious and less contagious. Vaccines and treatments exist, especially since, for the majority of patients, the disease resolves itself after a few weeks.