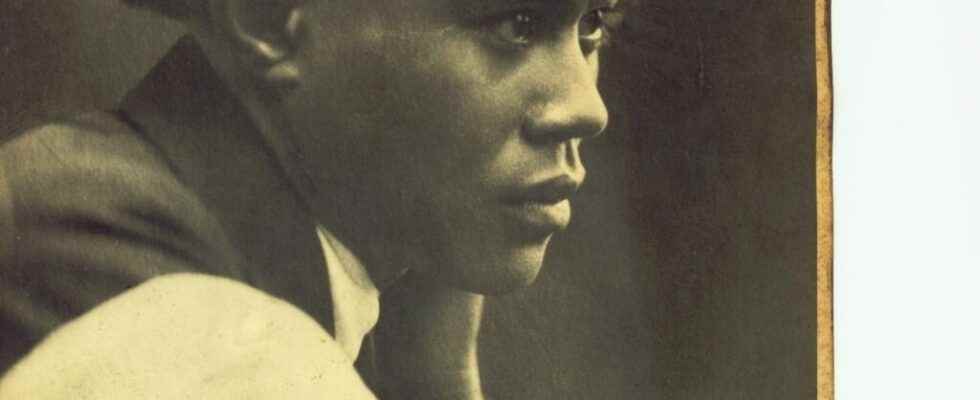

Jean-Joseph Rabearivelo is Madagascar’s greatest poet. In this second part of the chronicle “Writing paths” devoted to the biography of this writer and poet published by the researcher Claire Riffard, it will be a question of the protean work of Rabearivelo, its genesis, its reception and its modernity.

The great merit of the biographical account of Jean-Joseph Rabearivelo by Claire Riffard is to have been able to remind not without brilliance that writing and life were one and the same with this poet passionate about words and the imagination. Living in the harshest period of French colonization of the Big Island, this man born in 1903 and from the downgraded Merina (1) nobility, had found in writing the means to give meaning to his life emptied of his bearings. by social decline. ” Rabearivelo ultimately lived only for poetry “Senghor, who discovered him in the 1930s and 1940s, will say of him and contributed to the influence of his work.

Disappeared in tragic circumstances, at the early age of 34, Rabearivelo was a prolific author, with an estimated production of around 10,000 sheets, according to his biographer. Until recently, only a very small part of this work has been accessible to the general public, less than half. The rest, including the diaries referred to as the blue notebooks, remained buried for a long time in the family archives of the Rabearivelo, then transmitted at the beginning of the century to a team of researchers from the National Center for Scientific Research (CNRS), specialized in the work of safeguarding and promoting French-speaking manuscripts. It is to these researchers that we owe the complete works of the poet, published in two volumes, in 2008 and 2010 respectively.

A protean work

Self-taught, fascinated by French poetry, but inhabited by the images and rhythms of traditional Malagasy poetry, Rabearivelo published his first poems in French verse in 1921 and his first collection, The Cup of Ashes, in 1924, in Antananarivo. These first verses already show a great mastery of French prosody, even if they still smell of imitation of the poet’s Parnassian and romantic masters. Other collections will follow, with the titles Sylves (1927) and volumes (1928), with themes ranging from nature to the native land and exile, passing through love, oblivion and death. The author defined himself as a “post-symbolist” poet, but his originality consisted in writing both in Malagasy and in French. At the same time, he translated traditional Malagasy texts for French magazines.

” It is a bilingual and protean work, that of Jean-Joseph Rabearivelo “recalls Claire Riffard. And the biographer adds: Rabearivelo is also a novelist. He wrote two historical novels: L’Interférence and L’Aube rouge, the latter not having been published during his lifetime. Rabearivelo is also a playwright. He has written several commissioned plays. What is interesting to point out is that these are bilingual plays. I believe that Rabearivelo wanted to pay tribute to his country. And this country at the time was a country divided by colonization, but it was a country which had an immense culture of which he was an heir. And Rabearivelo, I believe, wanted to convey a complex country, a country made up of a Malagasy culture deeply anchored in it and a country also irrigated by external contributions, sometimes imposed, sometimes desired. This ambiguity is the engine of his writing. »

The ambiguity as a source and spring of the poetry of the Malagasy bard had already been underlined by Senghor who was especially familiar with the work of maturity of the poet, in particular his three most famous collections: Almost-dreams (1934), Translated from the night (1935) and Old Songs from the Countries of Imerina (1967).

Admirer of the work of the Malagasy poet, Senghor will publish in 1948 several of his poems in his famous Anthology of new black and Malagasy poetry in the French language, founder of French-speaking African literature. In his presentation, the leader of Negritude marveled at the freshness and harmony that emanated from the verses of his elder and celebrated their ” spontaneity of emotion “. ” Rabearivelo knows how to see and feel the sensitive world”, wrote Senghor. Above all, he knows how, beyond appearances, to grasp and translate the rhythm of their inner life. »

At the crossroads of worlds and influences

If Senghor’s words have certainly contributed to making Rabearivelo known throughout the French-speaking world, it would be a mistake to reduce this eminently sophisticated and elegant poetry to ” gushing springs of Imerina », as Senghor proposes in his Anthology.

The novelty of the beautiful biography of Claire Riffard is to have snatched the work of Rabearivelo from the folklore of the land to place it squarely in modernity, at the crossroads of worlds and influences where Baudelaire and Paul Valéry coexist with the Black Americans in whom the Malagasy poet recognized himself more than in the process of identity and rooting in blackness.

” Ihe question of negritude in Madagascar was not at all posed in the same terms as in Paris in 1935, emphasizes Claire Riffard. Rabearivelo reflected on the position of the extra-European intellectual. He used other words than those of negritude. One of the discoveries of the investigation carried out on Rabearivelo in recent years has been to bring to light his links with the poets of the ”Harlem-Renaissance” and the whole movement in the United States which valued the New Negro, the new Negro. We found the letters exchanged between Rabearivelo and Claude McKay, the author of Banjo. These letters show a great affection, a real friendship between the two writers. Rabearivelo finds himself, out of this binary relationship between the colony and colonial France, he finds himself integrated, invited into a much larger network which is that of the black intellectuals of his time. And it’s a fascinating avenue for rethinking the intellectual networks of this era which are not binary, which cross the Atlantic and not just the Mediterranean. »

“Fascination for the an-dafy”

This intellectual cosmopolitanism that Rabearivelo had chosen to define himself is illustrated by the poet’s epistolary friendships. His biography dwells at length on the exchanges that the Malagasy author maintained with writers and intellectuals from all over the world, from Guyanese René Maran to Frenchman Paul Valéry, via the American Claude McKay, the Japanese Kikuyu Mata, the Mauritian Robert-Edouard Hart, Mexican Alphonso Reyes and Algerian Jean Amrouche, to name but a few.

Cramped in Antananarivo under colonization, the poet lived intensely ” the fascination for the an-dafy, the overseas writes Riffard. He nourished himself intellectually and aesthetically on the return letters of his distant peers. Their responses replaced in a way the recognition that he would never receive from the colonial administration. Close to colonial circles in which he still had a few friends, Rabearivelo believed in the promise of assimilation, but he was bitterly disappointed.

” Rabearivelo never left Madagascar, says Claire Riffard. He asked the Governor-General, Léon Cayla, to be able to accompany the Malagasy delegation to the 1937 Arts and Techniques exhibition in Paris, but he was refused which deeply hurt him and which is believed to be with other facts at the origin of his deep despair in 1937 which will lead him to suicide. The colonial society of Antananarivo was aware that the promotion of an intellectual of the stature of Rabearivelo who reflected on his position as a colonized intellectual represented a danger for colonial policy and the Governor General understood this well. »

Also, the latter preferred to send to the Colonial Exhibition weavers, shoemakers, basket makers rather than intellectuals critical of his colonial policy. To the great despair of the poet and theoretician of the new Malagasy poetry, Rabearivelo, who dreamed so much of discovering France, his spiritual homeland. Depressed, disappointed, faced with family dramas and crumbling under debt, the greatest poet of Madagascar will end his days on June 22, 1937, by swallowing poison. Without forgetting to recount in detail in his diary the progressive grip of death.

” I kiss the family album. I blow a kiss to Baudelaire’s books… it’s 3:02 p.m. I’m going to drink… it’s drunk… I’m suffocating… »

Jean-Joseph Rabearivelo, a biography, by Claire Riffard. “Free Planet” collection, CNRS editions. 366 pages, 28 euros.

(1) Qualifier from “Merinas”, a people from the central highlands of Madagascar