Most teachers are faced with the problem of the difference in level of students in their class. For some of them and many parents of students, the solutions seem obvious: make those who do not have the level repeat a year to follow in the next class, establish classes or level groups to restore a certain homogeneity and make teaching more coherent. However, these two measures are part of the “pedagogical legends” that research work has called into question for a long time. Research which has, in part, contributed to greatly reducing the repetition rate in France over the last 50 years.

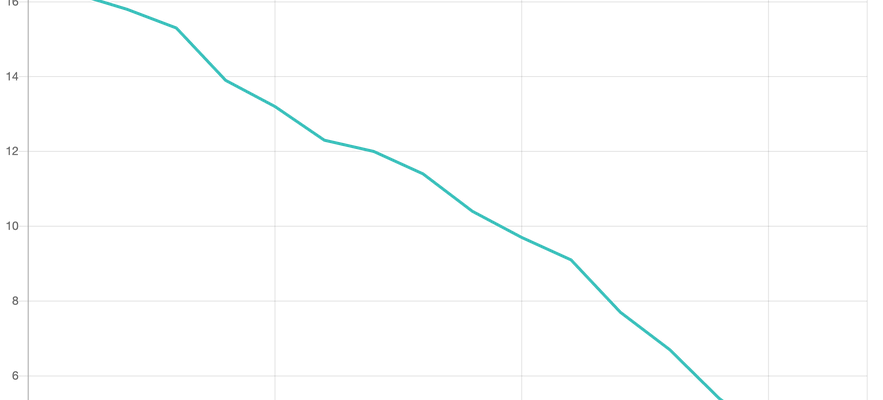

Evolution of late entry into sixth grade, as a percentage, excluding Segpa and Ulis in mainland France, DROM, in the Public and Private sector under contract.

© / DEPP, Education Information System.

Today, is grade repetition still too high, at the right level or too low? Nobody knows anything about it. Indeed, studies on the effectiveness of grade repetition give heterogeneous results: sometimes positive, often negative or zero. The most recent meta-analysis also indicates that the average effect, across the 84 studies analyzed, is zero. More precisely, this work tells us that the average repeater did not progress more by remaining in the same class than by moving to the next one. But this is only the average repeater. Around him, a small half of the repeaters were progressing less than if they had moved to the next class, and another small half were progressing more. In other words, according to the data examined by research studies, too many students were repeating a grade.

But what was true in a context with a high repetition rate (in 2005 in France, 17% of students entering sixth grade had repeated at least once) is not necessarily true in a context with a low repetition rate (4%). in 2021), because the population of repeaters is no longer the same. The more we limit repetition to students with very low academic levels, the more likely it is that their level will be too far from the higher class for them to benefit from it. The right question to ask is therefore: from what discrepancy between the student’s academic level and the expected level, or from what percentage of repeaters, does the negative effect of repeating become canceled and becomes positive? Reexamining research data from this perspective would be a rational way to determine an optimal repetition rate at each level.

A repeat costs 9,360 euros on average

This question would have a certain academic interest. But it becomes somewhat futile when we worry about the benefit/cost ratio. Indeed, a repetition is equivalent to a full year of schooling, i.e. 9,360 euros on average in 2021. For a lower cost, many other more efficient solutions exist, such as individual tutoring to help students with academic difficulties, to prevent or remediate a dropout. We would still have to reinvest at least a fraction of the savings made thanks to the reduction in repetitions in such interventions.

In conclusion, from the point of view of pure efficiency, we do not know which, lowering the repetition rate further or increasing it again, would have the best effect on student learning. On the other hand, from the point of view of efficiency, there is little doubt that increasing repetitions would have a cost disproportionate to the possible benefit and that such a financial investment would be much better used in other treatments of the difficulty school.

“It is difficult to understand that the scientific consensus was not followed by the minister”

Scientific results do not prescribe educational policy, however the best political decisions, in education as in health, are those which are duly and completely informed by the scientific knowledge consulted upstream of the decisions. On a subject on which the scientific consensus is so clear and on which several members of the scientific council of national education have alerted, it is difficult to understand why it was not followed by the minister. We may fear that students with disabilities will be the first victims of an increase in grade repetition, a measure that is so much easier (but so much less effective) than full inclusion with adjustments, adaptations and differentiated teaching.

Prudence now dictates that this new policy be tested locally and rigorously evaluated before considering generalization, which should be the default approach before any large-scale reform with uncertain consequences.

Franck Ramus is Director of Research at the CNRS and director of the “Cognitive Development and Pathology” team within the cognitive and psycholinguistic sciences laboratory at the Ecole Normale Supérieure in Paris.