Published on

Updated

Reading 3 min.

For the first time, a British teenager has had a neurostimulator implanted in his skull to reduce his severe epilepsy. In a few months, his seizures went from several hundred to just a few per day.

In the photo, Oran Knowlson looks exactly like an ordinary young teenager. He is actually the first patient in the world to test a new brain implant device that can control his epileptic seizures. With success.

Up to several hundred seizures every day

Oran, 13, who has ADHD and autism spectrum disorder, also suffers from Lennox-Gsataut syndrome, a form of treatment-resistant epilepsy that he developed at the age of three and which gives him dozens, if not hundreds, of seizures every day.Including seizures where he would fall to the ground, shake violently and lose consciousness. Sometimes he even stopped breathing and had to resort to emergency medication to resuscitate him.” her mother testifies to the BBC media.

An extreme situation which made it a good candidate for a solution, carried out by the CADET trial (Children’s Adaptive Deep brain stimulation for Epilepsy Trial). That of a neurostimulator implanted directly in the brain. Last October, at the age of 12, he became the first patient to be implanted with a brand new device.

An implant “screwed” into the skull bone

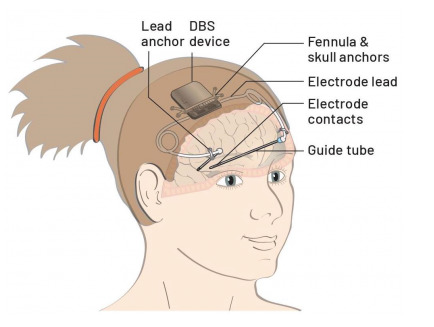

The operation lasted 8 hours and was impressive. The team, led by consultant pediatric neurosurgeon Martin Tisdall, inserted two electrodes deep into Oran’s brain until they reached the thalamus, a key relay station for neuronal information (with a margin of ‘error for placement of the probe less than one millimeter!)

The ends of the probes were connected to the neurostimulator, a 3.5 cm square, 0.6 cm thick device that was placed in a slot in Oran’s skull where the bone had been removed. The neurostimulator was then screwed into the surrounding skull, to anchor it in place.

Deep brain stimulation had previously been tested to treat childhood epilepsy, but until now, neurostimulators were placed in the chest, with wires running to the brain.

80% fewer seizures since implantation

“This study should allow us to determine whether deep brain stimulation is an effective treatment for this type of severe epilepsy” declared to the BBC Martin Tisdall, pediatric neurosurgeon who led the operation.

How does it work? Epileptic seizures are triggered by abnormal bursts of electrical activity in the brain. The device, which delivers a constant pulse of current, aims to block or disrupt the abnormal signals.

When it’s on, Oran doesn’t feel it. But he has to charge the device every day via wireless headphones, while going about his activities (like a normal teenager after all).

Seven months after the operation, the improvement is there: according to Justine Knowlson, Oran’s mother, “he is more alert and does not have seizures during the day.” His nocturnal seizures are also “shorter and less severe”. The teenager was also able to resume sporting activities, such as horse riding.

As part of the trial, a nurse with oxygen and one of her teachers are always nearby just in case. But neither has been necessary so far.

In the future, the team plans to make the neurostimulator respond in real time to changes in its brain activity (rather than constantly), with the aim of blocking seizures just as they are about to occur. But for Oran and his family, this implant represents impressive progress.

“The team at Great Ormond Street have given us hope…now the future looks brighter” concludes the mother.

The CADET (Children’s Adaptive Deep brain stimulation for Epilepsy Trial) pilot project will now recruit three more patients with Lennox-Gastaut syndrome, funded by the Royal Academy of Engineering, before 22 patients take part in the full trial, funded by GOSH Charity and LifeArc. The study is sponsored by University College London.