By Annalisa Bracco, Georgia Institute of Technology

Since mid-March 2023, mercury on the surface of the oceans climbs to unparalleled levels in 40 years of satellite monitoring, and the detrimental impact of this overheating is being felt around the world.

The Sea of Japan is 4 degrees Celsius warmer than average. The Indian monsoon, product of the strong thermal contrast between the lands and the seas, was well later provided that.

Spain, France, England and the whole of the Scandinavian Peninsula recorded levels of precipitation much lower than normal, probably due to an exceptional marine heat wave in the eastern North Atlantic. Sea surface temperatures were 1 to 3°C above average from the African coast to Iceland.

And on the European continent, the heat wave is currently unbearable, while we are breaking all records.

So what’s going on?

El Nino is partly responsible. This climatic phenomenon, which is currently developing in the equatorial Pacific Ocean, is characterized by warm waters in the central and eastern Pacific, which generally attenuates the trade winds, a regular wind from the tropics. This weakening of winds can in turn affect oceans and land around the world.

But other forces act on the temperature of the oceans.

At the base of everything, there is global warming, and the rising temperatures on the surface of continents like oceans for several decades due to human activities increasing the concentrations of greenhouse gases in the atmosphere.

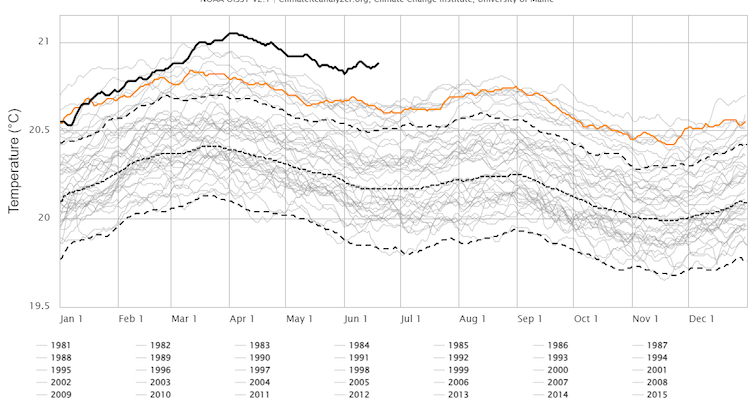

Sea surface temperatures are well above average since satellite monitoring began. The thick black line corresponds to 2023. The orange line corresponds to 2022. The 1982-2011 average corresponds to the dotted middle line. ClimateReanalyzer.org/NOAA

The planet also comes out of three years consecutive periods marked by La Niña, the inverse weather phenomenon of El Niño, and therefore characterized by colder waters that rise in the equatorial Pacific. La Niña has a cooling effect on a global scale that helps keep sea surface temperatures reasonable, but can also mask global warming. When this cooling effect stops, the heat then becomes more and more evident.

Arctic sea ice was also abnormally low in May and early June, another aggravating factor for ocean mercury. Because the melting ice can increase the temperature of the water, because of the deep waters absorbing the solar radiation that the white ice sent back up to there in space.

All these phenomena have cascading effects visible all over the world.

The effects of the extraordinary heat of the Atlantic

At the beginning of June 2023, I went for two weeks to the NORCE climate center in Bergen, Norway, to meet other oceanographers. Warm currents and unusually mild eastern winds from the North Atlantic made it unusually warm for this time of year, when heavy rain is normally seen on two out of three days.

The entire Norwegian agricultural sector is now preparing for a drought as severe as that of 2018, when yields were lower by 40% compared to normal. Our train from Bergen to Oslo was delayed for two hours because the brakes of a carriage had overheated and the 32°C temperatures approaching the capital were too high for them to cool down.

Many scientists have speculated about the causes of the abnormally high temperatures in the eastern North Atlantic, and several studies are underway.

The weakening of the winds made particularly weak theAzores High, a semi-permanent high pressure system over the Atlantic that influences weather conditions in Europe. Therefore, there was less Sahara dust over the ocean in the spring, potentially worsening the amount of solar radiation on the water. Another possible factor aggravating the heat of the oceans: the decrease in human-made emissions ofaerosols (fine airborne particles) in Europe and the United States in recent years. If this decrease has improved air quality, it is accompanied by a reduction – still poorly documented – ofcooling effect of these aerosols.

A late monsoon in South Asia

In the Indian Ocean, El Niño tends to cause the water to warm up in April and May, which can curb the indian monsoon whose importance is crucial for various activities.

This is probably what happened with a monsoon much weaker than normal from mid-May to mid-June 2023. This phenomenon is likely to become a major problem for much of South Asia, where most crops are still irrigated by rainwater and therefore heavily dependent on the summer monsoon.

India experienced sweltering temperatures in May and June 2023. Shutterstock

The Indian Ocean has also experienced a intense cyclone and sluggish in the Arabian Sea, which deprived the land of moisture and precipitation for weeks. Studies suggest that when the waters warm, storms slow down, gain strength and thus draw moisture into their core. A series of effects which, in the long term, can deprive the surrounding land masses of water, and thus increase the risk of drought, forest fires and sea heat waves.

In America the hurricane season on hold

In Atlantic, weakening trade winds due to El Niño tend to dampen hurricane activity, but warm Atlantic temperatures can offset this by giving these storms a boost. It therefore remains to be seen whether, whether or not autumn persists, the ocean heat will be able to outweigh the effects of El Niño or not.

THE marine heat waves can also have significant impacts on marine ecosystems, whitening coral reefs and thus causing the death or displacement of entire species that live there. The fish that depend on coral ecosystems feed a billion people around the world.

The reefs of the Galápagos Islands and those along the coasts of Colombia, Panama and Ecuador, for example, are already threatened with bleaching and disappearance by this year’s El Niño phenomenon. At other latitudes, in the Sea of Japan and in the Mediterranean, there is also a loss of biodiversity to the benefit of invasive species (the giant jellyfish in Asia and the lionfish in the Mediterranean) that can thrive in warmer waters.

These types of risks increase

The spring of 2023 has been extraordinary, with several chaotic weather events accompanying the formation of El Niño and unusually warm temperatures in many waters around the world. This type of phenomenon and the global warming of the oceans as well as the atmosphere feed on each other.

To reduce these risks, global warming should be reduced by limiting excessive emissions of greenhouse gases, such as fossil fuels, and moving towards a carbon neutral planet. People will also have to adapt to a warming climate and in which extreme events are more likely, and learn how to mitigate their impact.

Annalisa BraccoProfessor of Ocean and Climate Dynamics, Georgia Institute of Technology

This article is republished from The Conversation under Creative Commons license. Read theoriginal article.

![]()