At the Louis-Vuitton Foundation, the event is major. The culmination of four years of research carried out by Anne Temkin, chief curator at the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) in New York, and her counterpart Dorthe Aagesen, from the Statens Museum for Kunst (SMK) in Copenhagen, it brings together, until 9 September and for the first time in Paris, ten works appearing in The Red Workshop, a few kilometers from Issy-les-Moulineaux, where Henri Matisse created the painting. It was in 1911. Already recognized but not always understood, the 41-year-old artist then represented his work space, without omitting the paintings, sculptures and objects found there. The Young Sailor, Luxury, Swimmers, Nude with a white scarf or even a plate painted by the artist in 1907 are immortalized on canvas. With an audacity that surprises himself, the painter transforms the gray floor, furniture and walls of his studio into vast layers of “oxblood red, as if the blood had seeped in to dye everything”.

A strange destiny than that of The Red Workshop which, despite the desire of its creator to part with it, does not find a buyer. The painting remained with the painter until 1927, before passing into private hands, then finally being acquired by the MoMa in 1949. As for The Ladies of Avignon rounded up ten years earlier, Alfred Barr, the founder of the New York institution, had a nose. And, once again, France missed the boat. Ann Temkin returns, for L’Express, to the genesis and modernity of this work which remained unknown for a long time and which, from the 1950s, fascinated several generations of artists, with Mark Rothko in the lead.

L’Express: Matisse painted The Red Workshop for Sergei Shchukin, its main sponsor, who ultimately refused it. What caused the painting to confuse the person for whom it was intended and even the artist himself in this year of 1911?

Ann Temkin Of course, we can only guess at the real answer to this question. An important point to remember is that Shchukin declined the painting based solely on a small watercolor that Matisse sent him by mail, accompanying a letter giving a brief description of the painting. Watercolor could not convey the power of paint. In the letter, Matisse tells Shchukin that the painting is “surprising.” Yes, I think even he was surprised! That’s what’s amazing about great art: the process of creating the work takes the artist to a place he didn’t anticipate and can’t even explain.

Can we consider this work as a pictorial revolution in the sense that it introduces monochrome into the vocabulary of modern art?

The painting is what one might call near-monochrome, because, of course, the red does not cover the entire composition. The most striking thing is that Matisse leaves there the works that he created and that he exhibited in his studio. It’s amazing to imagine what a big gamble the artist took in adding the red layer over what was previously a fairly simple descriptive scene. Yet this approach follows the logic of his other works of the period, disrupting traditional Western pictorial concerns, such as background and foreground, or light and shadow.

Henri Matisse, “Young Sailor (II)”, 1906.

/ © Estate of H. Matisse 2024 © The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Dist. RMN-Grand Palais / image of the MMA

Is it a portrait, a snapshot, of the artist’s own life?

We understand, from this painting, that Matisse set up his studio as a quasi-domestic setting. We see that he populated the place with decorative objects that he collected and that were dear to him – textiles and ceramics, for example. We also see that he loved displaying his own artwork and having comfortable furniture that one would associate more with a home, like a grandfather clock. We know that he loved welcoming his family and friends to this workshop in Issy-les-Moulineaux. It was sort of both a social space and a private work space.

In what The Red Workshop is it already part of a form of abstraction?

The way the red spreads all over the canvas, completely unrelated to a realistic depiction of the piece – it wasn’t red! – makes the painting a flat plane in a very radical way for the time. Paradoxically, the composition introduces an abstract field of color, or a field of imagination, even if it remains a fairly faithful representation of a specific piece at a specific moment. It is both a landmark in the centuries-old tradition of studio paintings and a fundamental work of modern art.

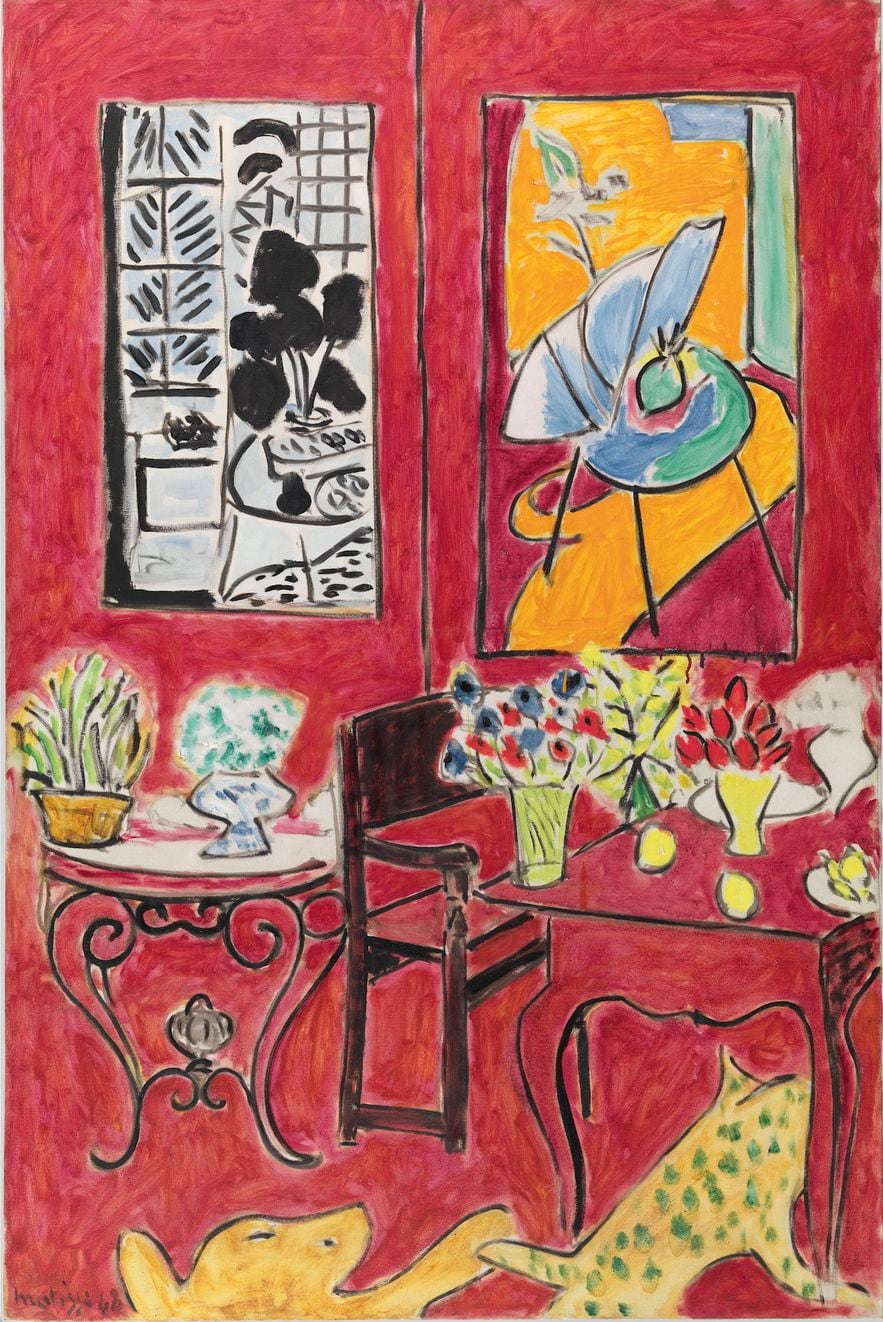

Henri Matisse, “Great Red Interior”, 1948.

/ © Estate H. Matisse 2024 © Center Pompidou, MNAM-CCI, Dist. RMN – Grand Palais /Audrey Laurans

What connects The Red Workshop and the Large red interior made by Matisse thirty-seven years later and also presented in the exhibition?

This connection was not explicitly established by the artist, but one cannot help but see the relationship between the subject and the color – even if the hue of the Large interior from 1948 is a bright cadmium red, rather than the darker Venetian red of the 1911 painting. I find it very moving that, as Matisse comes to the end of his painting career, he thinks back to The Red Workshop. It was a painting that he admitted he did not fully understand immediately after completing it, and it appears that Shchukin’s rejection of the work may have reinforced his own doubts. At the moment when he realizes the Large red interiorat the same time as a new generation of artists discovers and is fascinated by The Red Workshopperhaps Matisse also woke up there.

There is a correlation of destinies between the painting of Matisse and that of Picasso, The Ladies of Avignonfor example, both disdained by France then acquired by the MoMA, which rediscovered them to the world…

There is a lot to be said about this observation – it is more than a question! – because it touches on a number of complex issues. A short explanation to give is perhaps that the MoMa was and still is a private museum institution, while French art museums at the time were managed by the State or the City. Advocating for the new and risking bold decisions was part of MoMa’s DNA from the beginning. This was probably an easier position to maintain outside the government bureaucracy of the 1930s and 1940s, when modern art was still largely viewed with skepticism.

.