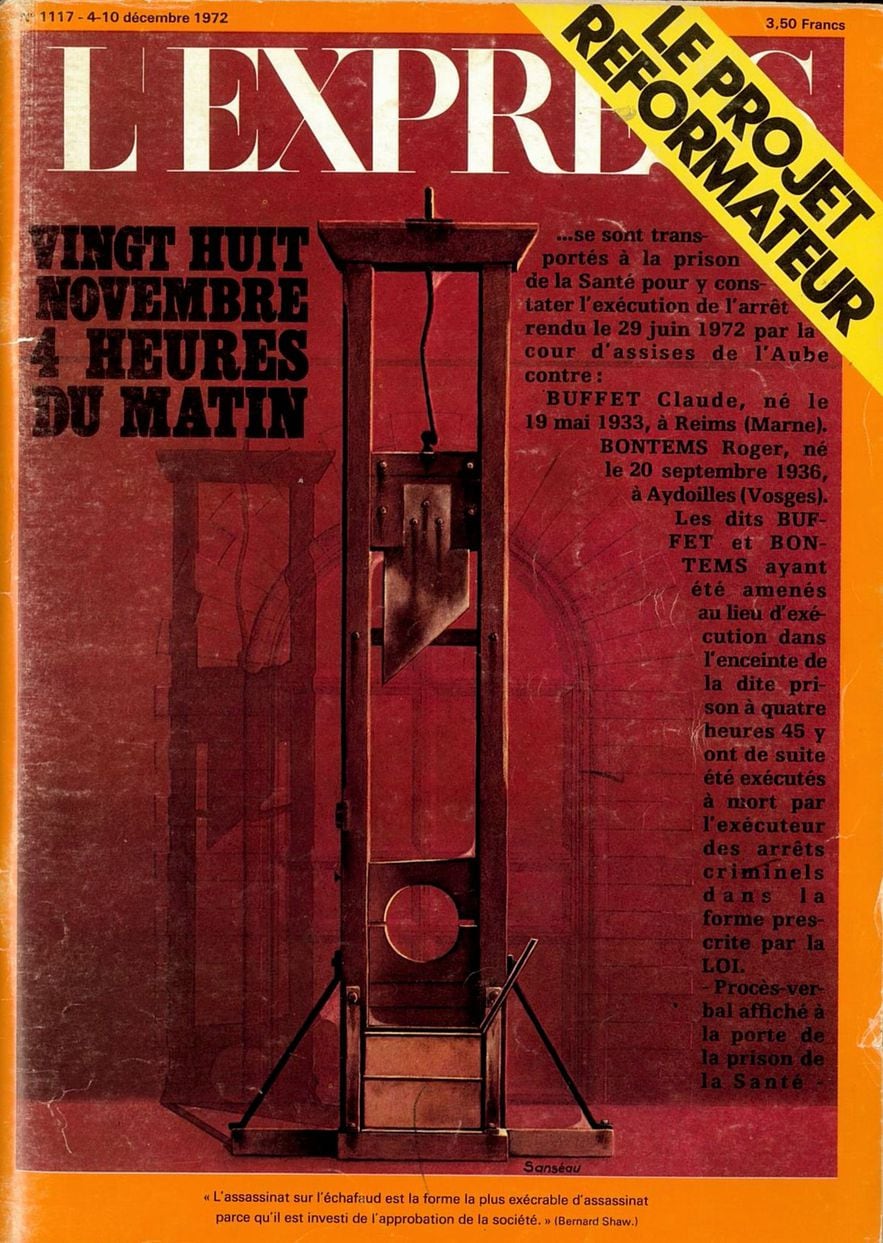

At dawn on November 28, 1972, Robert Badinter attends the execution of his client Roger Bontems at La Santé prison. Next week, alongside his historic lawyer, L’Express is committed to the abolition of the death penalty by publishing, from the pen of Jacques Derogy, the account of the ceremonial preceding the execution of the condemned. This violation of the Penal Code will result in the newspaper being fined 5,000 francs. In this same issue, Robert Badinter develops the arguments that motivate his fight and touches on the fundamental questions that we do not want to ask.

L’Express of December 4, 1972

The alibi

All the experience of abolitionist countries has confirmed it: the death penalty is useless. So why, alone in Western Europe, does France maintain it?

Thus the list of capital executions that we may have at one time believed to be completed is not closed. Thus the centuries-old alliance between France and the guillotine was renewed. And the French, according to polls shameful for those who chose to publish them while the fate of two men was in the balance, the majority of the French would be satisfied. How can we not wonder, beyond the renewed debate between supporters and opponents of the death penalty: why are the French so attached to it?

Here is a great country, ours, which, alone of the religious, cultural, political community to which it belongs, retains the death penalty. All the close companions of our long history have gradually freed themselves from it. Stubbornly, the French remained faithful to him. What function or what secret anxiety does the death penalty satisfy among so many of our fellow citizens? So what is the buried truth revealed by this tragic sign that must finally be deciphered?

It is not that France experiences a fever of bloody crime greater than that of other Western European countries. Crime is no more rampant there than in Germany, Great Britain or Belgium, all abolitionist. It is not that French justice is governed by a particular repressive passion. She is undoubtedly not the most indulgent or the most concerned with understanding criminals. But it is far from being the most rigorous or the most inhumane. It’s not that the French are carried away by some kind of blood passion. Undoubtedly the death penalty plays in France the liberating role of a collective psychodrama where the aggression and morbid violence that each person carries within themselves are released. But the tension is no less in neighboring countries, whose customs and centuries-old anxieties are no different from ours. SO ?

Robert Badinter (c, bottom), lawyer for Patrick Henry (c, glasses) during his trial on January 18, 1977 in Paris

© / afp.com/STF

It is because the death penalty is a convenient alibi for good consciences that it persists. It is because the debate on the death penalty allows other debates, even more pressing, to be sidestepped, that it continues, interminably, as a sort of tragic diversion from fundamental questions that we do not want. settle down.

“The State can, ultimately, dispose of human life”

The first is that of the value given to the human person in a society. Death penalty enthusiasts always come back to the famous apostrophe: “Let gentlemen assassins begin….” They will never start, precisely because they are murderers. But if a society proclaims that human life has absolute value, it can no longer take, even legally, anyone’s life. If human life is sacred, it remains so even in the person of the sacrilegious, the assassin. When a country, therefore, refuses to abolish the death penalty, it refuses at the same time to consider the right to life as absolute, as sacred. This is the case in France at the moment.

This terrible observation calls for a reminder, which reinforces it. France is also the only democratic country in Western Europe which has avoided signing the European Convention on Human Rights, the first affirmation of which is the absolute respect due to the human person. These two signs: maintenance of the death penalty, refusal to condemn torture, combine in a secret acceptance that violence, even deadly, even legalized, is not useless in the government of societies.

L’Express of December 4, 1972.

© / The Express

What, ultimately, does the abolition of the death penalty and the refusal of torture mean, other than that the individual, even the most guilty, still has the right to have his person and his life respected by society? This is the only way to establish the primacy of the individual over the State. To maintain, on the contrary, the death penalty, to secretly resign oneself to the conception that torture is useful, in certain circumstances where the superior interest of the Nation or of Justice is invoked, is to recognize to the State , ultimately, the power to dispose of the person and the very life of the subject. This explains the fundamental historical connection between dictatorship, right or left, and the death penalty. It is sufficient to note in this regard that the only countries in Europe where the death penalty is in force are countries where the primacy of the State over the individual is a dogma. In ours, it is a historical survival. But it is not without deep roots in the unacknowledged or resigned conception that the French have of human rights vis-à-vis the State. By denying, precisely, to the most fallen or the most dangerous of its members an absolute right to respect for their life, France implicitly only grants relative value to the human person. It admits that society, or rather its institutional expression: the State, can ultimately control human life. In this respect, it turns out to be totalitarian.

Robert Badinter’s fight for the abolition of the death penalty in L’Express of December 4, 1972.

© / The Express

“All the experience of abolitionist countries has confirmed it: the death penalty is useless”

The same ambiguity surrounds the second question, which is readily discussed but without asking it in exact terms: that of the usefulness of the death penalty – not the usefulness invoked, that of intimidating criminals – but the usefulness unacknowledged, secret, essential, which actually motivates the maintenance of the death penalty. It is a long time, in fact, that for those who seriously question the relationship between bloody crime and the death penalty, the answer is written in the facts. The abolition of the death penalty has no impact on the evolution of crime. It would probably be absurd or exaggerated to say that abolition reduces crime. But it is contrary to the truth to say that it increases it. All the experience of abolitionist countries has confirmed it: the death penalty is useless. Bloody criminality has never retreated before it. But we continue to refuse this fact. By lack of information or even more because we do not want to admit it. This paralogical attitude, so passionately maintained, is significant. It proceeds from a secret desire to maintain the existing state of things, not because it is morally justifiable, but because it is useful, or simply convenient. Because the death penalty is convenient. As it is only practiced very exceptionally, it no longer offends sensibilities. But the fact that it is possible still ensures its secret office – which is to give a good conscience to its supporters. Because, precisely because the death penalty exists and almost all criminals are spared it, most French people have the feeling of being generous towards them. Leaving them alive seems such an important grace, such lenient treatment, that for the rest, that is to say the essential, the fate that has been done to them, any rotten person can provide for it with indifference. common.

It is insufficient, in this regard, to say that it would be in vain to abolish the death penalty if there was not, finally, a real prison reform which would make it possible to take care of those who are not would run more. Because the problem thus posed is exact, but limited because it only concerns, by definition, a few exceptional cases. The real problem is broader — and the more secret link between the death penalty and the prison situation. The death penalty, precisely because it is rarely pronounced and exceptionally carried out, is the alibi of good consciences, the moral justification of penitentiary leprosariums. After all, it’s better to be alive and a leper than dead. Especially when lepers are hidden from the attention of the healthy, when they are as if cut off from the world, by thought as much as by the walls, in their closed universe. And that attention is only paid to them, most often, when a slave insurrection, a jacquerie, occurs. Now the revolt of slaves, the uprising of those to whom life is granted, which has become a supreme favor even though it is the first and most absolute of rights, what do they call, for the right-thinking, if not death of those who ignore their generosity?

So everything comes together and fits together. The death penalty makes it possible to ignore, and even worse, to justify maintaining the current prison situation. We could have killed these criminals. They are still alive. The demand for humanity is satisfied, at very little cost. But if we abolish the death penalty, good consciences will at the same time lose their alibi. No more evasions. This mask of humanity that prison reality veils simply because those who live it have preserved their lives will be torn away. We will then have to wonder about prisons and what is happening there. The death penalty, on the contrary, allows us to hide and sidestep this fundamental question. It is the mark of a society which prefers to stick to the survival of the magical rites of purifying human sacrifice rather than confronting in their reality the perils of our time.

.