In the administrative world, the undoable is the enemy of the good. Take the Taquet law on child protection, which came into force on February 1. It provides for a ban on hotel accommodation for young people dependent on child welfare (ASE). This type of accommodation was deemed “unsafe” and “fundamentally unsuitable for the reception and support of minors” by a report of the General Inspectorate of Social Affairs (IGAS), in 2020. Only young people aged 16 to 21 will now be able, through an exemption, to be sheltered in this type of structure for a maximum period of two months, only for “situations emergency”, and with “night and day” surveillance by a “trained” professional. “The problem is that this law is in fact inapplicable,” warns François Sauvadet, president of the association of French departments.

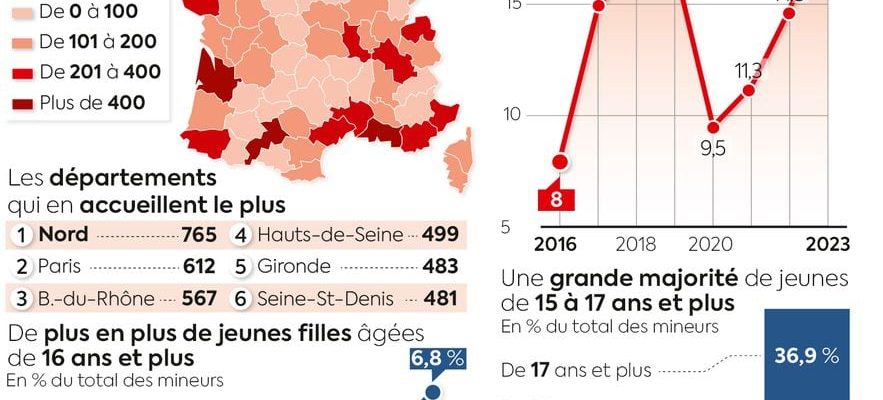

The former minister, president of the Côte d’Or departmental council, speaks of an “untenable situation”. A sort of bottleneck between a massive influx of minors and this law whose main principles contrast with the modesty of the means on the ground. It is up to the departments to welcome those called unaccompanied minors (UMAs), most of whom are foreigners, often arriving in France after a long migratory journey. In 2023, 19,370 of these children were entrusted to Child Welfare (ASE) – an increase of 31% in one year.

“On my territory alone, 37 minors are currently housed in hotels, due to a lack of places available elsewhere. What should we do with them? Sometimes, unfortunately, we have no choice, it’s the hotel or the street” , insists François Sauvadet. The question of the increase in unaccompanied minors particularly worries the president: in his department, 163 young people were entrusted to the ASE in 2023, compared to 123 in 2022 – or 40 additional people to be accommodated. “But there are also all those who presented themselves as minors when they were not and we had to take charge of the evaluation of their majority, in a context of lack of staff and recruitment difficulties,” he explains.

According to the latest annual report of the National Unaccompanied Minors Mission (MNMNA) of the Ministry of Justice, published in 2022, this increase in the number of young migrants in the territory is explained in particular by the end of successive state of emergency laws, restrictions on displacements and temporary border closures, the evolution of migratory routes or even the invasion of Ukraine by Russia. Coming primarily from Ivory Coast, Guinea, Tunisia, Mali and/or Afghanistan, these young people arrive with “traumatic life paths”, and “degraded health situations”, particularly for young girls – the number of which has continued to increase since 2017, the officials write.

System out of breath

The system supposed to organize the reception of these migrants, whom the law protects to the point of making them indeportable – as long as their minority is recognized – seems to be running out of steam. On their arrival in France, these unaccompanied minors must be welcomed by the departments, which are obliged to organize temporary emergency reception for a maximum period of five days, the time to assess their actual minority as well as their family isolation. To do this, interviews conducted by professionals question and cross-check the information communicated by these young people: country and region of origin, marital status, family composition, living conditions, reasons for departure, etc. In case of doubt, the supporting documents of the migrant can be transmitted to the services fighting against document fraud. The courts can also be contacted to carry out radiological bone examinations – a method practiced for around ten years, the reliability of which is contested by several associations and national authorities. “Many have no papers, damaged or unclear supporting documents. How can you really tell the difference between a boy of 16 and a half years old and a young adult of 18 years old?” asks Chantal Raffanel, volunteer for the association of help to migrants Rosmerta. In its premises in Vaucluse, it regularly takes care of young people “arbitrarily refused by the ASE”, who turn out, after appeal, to ultimately be minors. “Conversely, many are adults,” opposes François Sauvadet. “More and more associations are being contacted, the evaluation is taking longer and longer, and is therefore costing more and more money… We can no longer cope,” he assures us.

It is only at the end of this administrative phase that judicial protection begins. If the minority is recognized, the young migrant can benefit from placement in a departmental children’s home. But the machine, in theory well-established, stalls. The various annual reports of the MNMNA, as well as two successive reports from the Senate in 2017 And 2021, draw the same observation: the system is saturated, and no longer allows these young people to be properly accommodated. “The rapid growth in the number of unaccompanied minors and the constraints of their care quickly imposed (…) a massive recourse to hotels to accommodate them since 2013, even if this solution was never presented as desirable or sustainable by any of the actors”, criticizes the IGAS in its 2020 report. According to senior officials, 95% of young people accommodated in the hotel by child protection were unaccompanied minors in 2020. This mode accommodation presents “well-identified dangers” for all minors, they say, such as “poor control of the quality of reception areas, promiscuity in rooms, isolation due to the absence of staff educational or ASE correspondents, weak surveillance or even the proximity of places of trafficking.

“Unprecedented saturation”

In such a context, the association of French departments points to ever higher expenses for the care of unaccompanied minors. In a statement published on February 5, the body mentions an investment of “1.5 billion euros” for these miners alone, out of a total budget of 9 billion euros for the ASE. Especially since the publication of the Taquet law, young people aged 18 to 21 entrusted to the ASE before their majority will have to continue to be taken care of if they do not benefit from sufficient resources or family support. “We ask the State to regain control of the care of unaccompanied minors upon their arrival in France, while their minority is assessed,” calls for François Sauvadet in particular. Despite State participation – 500 euros per young person for the minority assessment and 90 euros per day for shelter for 14 days – certain departments have decided to react by temporarily stopping their support for unaccompanied minors.

3791 isolated minors society

© / Art Press

In September 2023, the departmental council of the Territoire de Belfort was the first to take a drastic measure, by unanimously voting for a motion aimed at limiting the reception of these minors. “Between those sent by the Ztat as part of the distribution and those who presented themselves as minors spontaneously and who had to be evaluated, we encountered an unprecedented situation of saturation. At the time, we counted 89 people to be taken care of, for a reception offer of 61 places”, deplores Florian Bouquet, the president of the department, to L’Express. According to the MNMNA’s calculation, nine additional minors were finally entrusted to the ASE on a long-term basis between 2022 and 2023. “On paper, it doesn’t seem like much, but it’s the straw that breaks the camel’s back. I don’t have a plethora of buildings and social workers, we had to put a stop to these spontaneous arrivals”, justifies the president.

Since then, other departments, such as Vaucluse, Vienne, Jura and Ain have made similar decisions. On November 29, Jean Deguerry, president of the Ain department, announced for example the temporary suspension, for “at least three months”, of the care of unaccompanied minors arriving directly in the department. “Despite the opening of more than 150 accommodation places in 2023, the department no longer has solutions, neither temporary nor lasting,” indicated the Departmental Council in a statement, asking the government “the means to act”. The decision to temporarily suspend the care of unaccompanied minors, which was to take effect on December 1, was nevertheless suspended by the administrative court of Lyon, seized by various associations such as the League for Human Rights or the Group of support information for immigrants (Gisti). “There is a legal obligation for departments to assess the situation of young people to know whether or not they should be placed in the ASE. These decisions to temporarily stop reception, which have multiplied since the summer last, are completely illegal”, underlines Solène Ducci, lawyer at Gisti.

In the Vaucluse department, where a poster posted at the Departmental Council indicated for around ten days, last November, that the reception of unaccompanied minors was closed, President Dominique Santi justifies her decision by “overwhelmed staff”, who “can no longer meet demand”. “In 2023, nearly 1,500 people appeared before our services explaining that they were minors, while 80% were subsequently assessed as adults. Costs are exploding: 8.4 million euros for our department, of which the State only covers 5%,” she argues. According to the latest figures from the MNMA, 165 unaccompanied minors were actually entrusted by judicial decisions to the Vaucluse ASE in 2023, compared to 124 in 2022. “In absolute value, it is not a tsunami either. It is in fact a political choice: if the departments really wanted to invest in welcoming these unaccompanied minors, they could,” believes Chantal Raffanel, who has filed, with the Rosmerta association, several summary proceedings against the department before the administrative court of Nîmes for this lack of support.

“Here, they return to their childhood place”

The rare host families asked to take care of unaccompanied minors indicate, for their part, that they are more than overwhelmed. “I have approval for three children, but the State has regularly granted me extensions over the last few years, to urgently accommodate more unaccompanied minors in particular,” testifies Louise*, family assistant in Côtes d’Armor. Pauline* had the same experience. She has welcomed up to five children in recent years, with approval initially granted for three. “Here, they settle down, resume their childhood place, join their culture with ours. I do not understand why we continue to park them in hotels while waiting for their majority to be assessed, or for lack of other solutions “accommodation,” she laments.

Aware of the situation, the president of the parliamentary delegation for children’s rights Perrine Goulet pleads for the opening of new places in reception centers, as well as “reflections to favor other systems, such as the systematic search for trustworthy third party or sustainable and voluntary reception”, which consists of voluntarily welcoming a minor into a local home and “is currently only implemented in two departments”. It’s urgent. “The risk is to end up with young people left to their own devices, exposed to dangers or who would fall into delinquency,” warns the MP.

* Names have been changed.

.