How do you know each other?

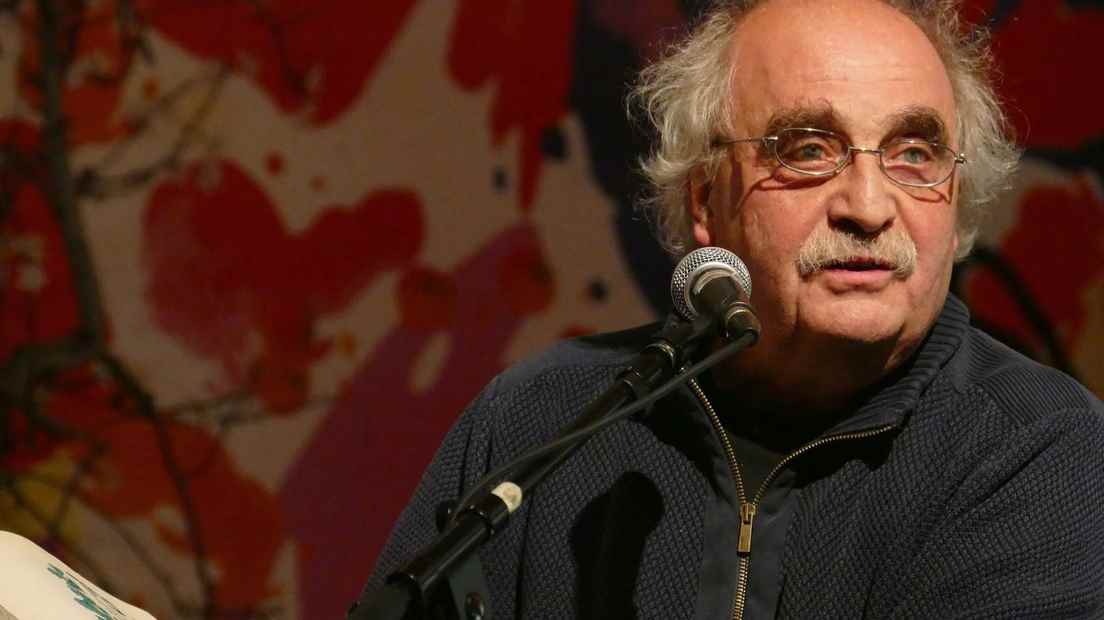

Arjeh: Adriaan was my GP and vice versa I worked for the local newspaper he read. Our sons used to play for the same football club, where we regularly stood along the line together. We talked a lot about the war. Our sons sometimes criticized us for forgetting to encourage them.

How did the story of Nico van Nieuwenhuysen come your way?

Arjeh: The story is unknown to many people. I had it on my radar for a while. For example, I once made an article for a supplement of a newspaper. This doctor also passed by. His story intrigued me greatly. The story went that he had two heads of murdered Russians on his desk as a kind of study object.

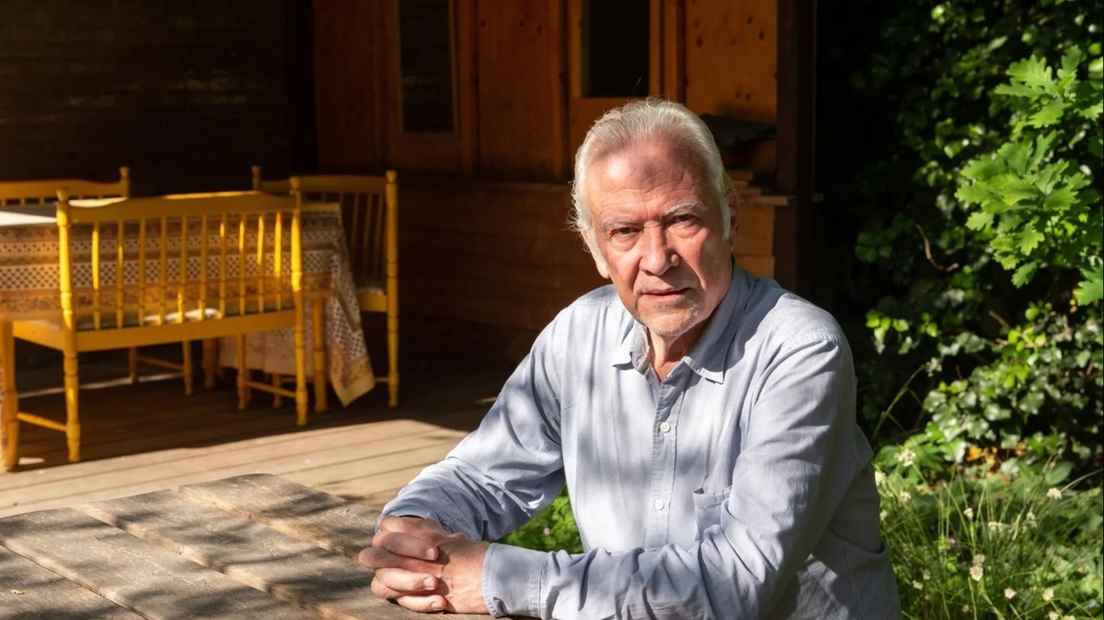

Adriaan: We once dived into the National Archives in The Hague to find out more about this man. Initially out of pure interest. We found a lot about him, but the most important golden opportunity came through a contact from Arjeh. That is how we came into contact with one of his grandsons, Nicolaas-John from America. Through him we have acquired a huge amount of documents and images.

Arjeh: Then it became a big project.

What was it like for his grandson to participate in this dark story about his own family history?

Arjeh: He had been thinking about doing something with his grandfather’s history for some time and he was eager to cooperate. Like us, he was very curious and wanted to understand how it is possible that someone who has sworn to always put the patient’s best interests first can make such a radically different choice. It was an even tougher process for him than it was for us.

Adriaan: It is very brave of him to participate in this. He wanted to contribute by publicizing what it was like at the time. You can also see it in his choice of profession. He is a psychiatrist in California and works with veterans there. We also ask him in the book if he is trying to make amends for what his grandfather did wrong. He confirms that. Another grandson of Nico is also still alive, but he wants nothing to do with this family history. He even changed his last name.

Why is it important that Nieuwenhuysen’s story is written down?

Arjeh: It is a black page from the past. You often see people turning their heads away from this subject, but it really is part of the history of Amersfoort.

Adriaan: This book gives you a small personalized insight into what it was like for the wife and sons of this wrong man to live after the war. What happened to the judiciary? What happened to their belongings? What happened to the schools? That is all covered. Before the war it was a wealthy family and after the war they lived under an administrator.

What impact does this part of history have on Amersfoort?

Adriaan: It is part of the history of Kamp Amersfoort. A historian who has dealt with the history of Kamp Amersfoort once called it an important hiatus. That has now been fulfilled with this book.

Arjeh: Camp Amersfoort is part of the history of Amersfoort, Amersfoort people are still insufficiently aware of that.

Adriaan: Through this project we have been able to get a small insight into what is called The Netherlands Management Institute. They managed goods and property of the wrong Dutch after the war. But that itself was also a dubious club with a lot of corruption, also in the Amersfoort department. A historian should dive into this again.

After writing this biography, how do you relate to the main character?

Arjeh: I’ve always been fascinated by choices people made during the war. That probably has to do with my background, because I have Jewish parents. So they suffered greatly during the war from choices made by others. I am convinced that almost everyone in a certain situation can make wrong choices.

Adriaan: What I notice as a person: you come very close to the main character, the choices he makes and that family. I myself have been a general practitioner in Amersfoort for 35 years. With all the specialists around, it is a kind of community. If this black page does not get a place in that history, then something is fundamentally wrong. It’s something you should look at anyway. He’s one of us. Then you can’t say: sorry I have nothing to do with that. I thought that was an important motive to keep myself busy with it.

Do we discover a piece of humanity in him somewhere in the book?

Adriaan: We have discovered a piece of humanity. In the official report, all his abuses and failure to recognize illnesses have been discussed. We went looking for prisoner health cards. These are cards with medical data that doctors kept about their patients. They were all destroyed in Kamp Amersfoort. Some prisoners were sent to camp Vught. We did find old disease cards, which showed that he kept the disease cards reasonably carefully.

The book will be presented on 19 January during the annual commemoration in Kamp Amersfoort. A few days later, on Sunday afternoon January 22 at 2.30 pm, the authors will be in the Eemland library to discuss the many ethical issues that arise in the book. The building where the doctor once lived still exists. It is a striking white notary’s office on the Utrechtseweg; Villa Meerwegen.