How do French scientists at the National Institute of Health and Medical Research (Inserm) perceive respect for integrity and scientific ethics in their work? To answer this question, researchers from the Sorbonne Sociological Analysis Methods Study Group (Gemass), a joint CNRS and Sorbonne University research unit, submitted a questionnaire between June and September 2023 to 1,240 staff of the world’s second largest research institute in the health sector. Their investigation published this Monday March 4 – the second of its kind only in France – provides answers that allow us to better understand the problems encountered by the world of science.

Ethics and scientific integrity, which aim to guarantee that research work is honest and rigorous and to consolidate the bond of trust with society, have become increasingly important subjects in recent years, particularly because – or thanks – to the Covid-19 crisis. A period during which confidence in science may have appeared shaken, in particular due to hazardous communication – or even the making of conspiratorial remarks – by certain doctors or researchers. “In addition, this type of work almost does not exist in France: we suffer from a significant deficit compared to the United States or the Netherlands. With this survey and the one we carried out in 2022 within the CNRS, this allows us to see things a little more clearly,” says Michel Dubois, sociologist, research director at the CNRS and co-author of the report with Catherine Guaspare, also a sociologist at the CNRS.

Signing studies without having participated in them

The questionnaire aimed in particular to question researchers about their perception of their own behavior in terms of respect for scientific ethics: in short, to ask them to carry out a self-criticism of their problematic behavior or behavior. “Certain responses, without being omnipresent, contribute to fueling the famous adage: everyone does it,” notes the report. For example, 30% of respondents admit to deliberately delaying the communication of results to publish them in a high-impact journal which earns more points allowing them to obtain funding and/or advance their career. “Intentionally delaying the communication of results for personal gain compromises the rapid dissemination of scientific knowledge,” remind the authors.

More worrying, 23% of respondents confessed to including a colleague as the author of their study even if he or she did not contribute. A practice highlighted in particular by the multiple scandals at the IHU in Marseille when it was headed by Didier Raoult. “There is a sort of informal economy that operates in the research units, with exchanges around these signatures,” explains Michel Dubois. The most common being that a team leader signs the work of his subordinates, even if he did not participate in it. 22% of respondents also indicate that they do not submit negative results for publication, while 11% say they modify the methodology or direction of a research project in order to meet the requirements of a funder.

While the vast majority of respondents perceive themselves as having integrity, the majority have the feeling of working in an environment in which questionable practices are too often tolerated and are harsh regarding the behavior of their peers. Thus, 60% consider that certain colleagues include authors in their studies who have never participated in their work. Nearly one in two respondents consider that their colleagues do not hesitate to embellish the results of a project in order to better convince an evaluator of the importance of their contribution. And between three and four respondents in ten consider that their peers regularly avoid presenting data that could contradict their initial hypotheses, or that they are capable of deliberately using a questionable or lax statistical technique in order to validate the meaning of ‘a search result.

Confidence to maintain and strengthen

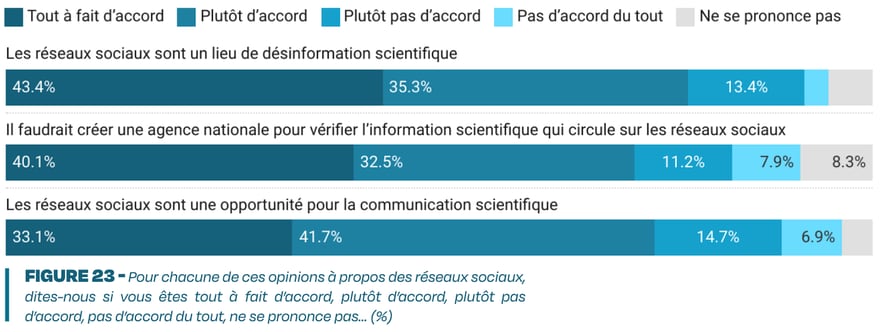

The survey above all notes an “underinvestment in ethical, moral and political questions”, since only a third of respondents have thoughts on the moral and political consequences of their work. More reassuringly, researchers show great caution regarding external communication. “Most believe that if they express themselves publicly, they must limit themselves to their area of specialty and/or indicate whether it is a personal or professional opinion,” specifies Michel Dubois. They are also very demanding a form of control over speech on social networks. “70% want scientific information to be regulated, with some putting forward the idea of a national agency for the control of scientific information,” adds the sociologist.

Results of the survey carried out by GEMASS, CNRS and Sorbonne University researchers.

© / GEMASS, CNRS – Sorbonne University

Another striking fact is that almost all respondents (9 out of 10) believe that there is a crisis of confidence, general or limited, between science and society. “And yet, recent work on the public image of science highlights the high level of trust the general public has in scientists who work in organizations such as Inserm,” indicates Michel Dubois. Too hard on themselves, researchers? In any case, they express fears that the world of research would benefit from looking into further. “It seems at least as interesting to study what leads a very minority part of public opinion to not want to rely on scientific opinion, as to understand the importance that scientists sometimes give to this minority voice which for many obscures majority assent”, write the authors of the survey. Whether justified or not, this feeling of crisis can have negative effects in the more or less long term, both on society, but also – and above all – the world of research.

.