When, in the fall of 1944, Erik af Klint, vice-admiral of the Royal Swedish Navy, learned of the last wishes of his aunt Hilma who had just died, he found himself in possession of sealed boxes. With a strict posthumous instruction: wait at least twenty years to open them. It was therefore only at the end of the 1960s that more than 1,200 paintings emerged from the shadows. All abstract and accompanied by 150 complex notebooks. But it would take two more decades for the secret production of the Swedish painter to be shown to the general public, in Los Angeles, in 1986, in the exhibition “Spiritual in Art: Abstract paintings 1890-1895”. These will be the beginnings of international recognition and the progressive discovery of a pioneer, whose work largely precedes the historical birth of abstraction dated by art history in 1912 with illustrious representatives named Kandisky, Mondrian or Kupka.

For almost forty years, Hilma af Klint led a double life. Born in 1862 into a family of ennobled officers, keen on astronomy and mathematics, she trained at the Fine Arts in Stockholm, one of the rare artistic institutions to welcome women. His first landscapes show a precocious talent, like the canvas that a Corot could have signed which we find at the opening of the retrospective proposed at the Guggenheim Foundation in Bilbao. From this mastered naturalist painting, the artist will also make his “official” activity and his livelihood throughout his life.

Photograph of Hilma af Klint in her Hamngattan studio in Stockholm.

/ © The Hilma af Klint Foundation, Bilbao 2024

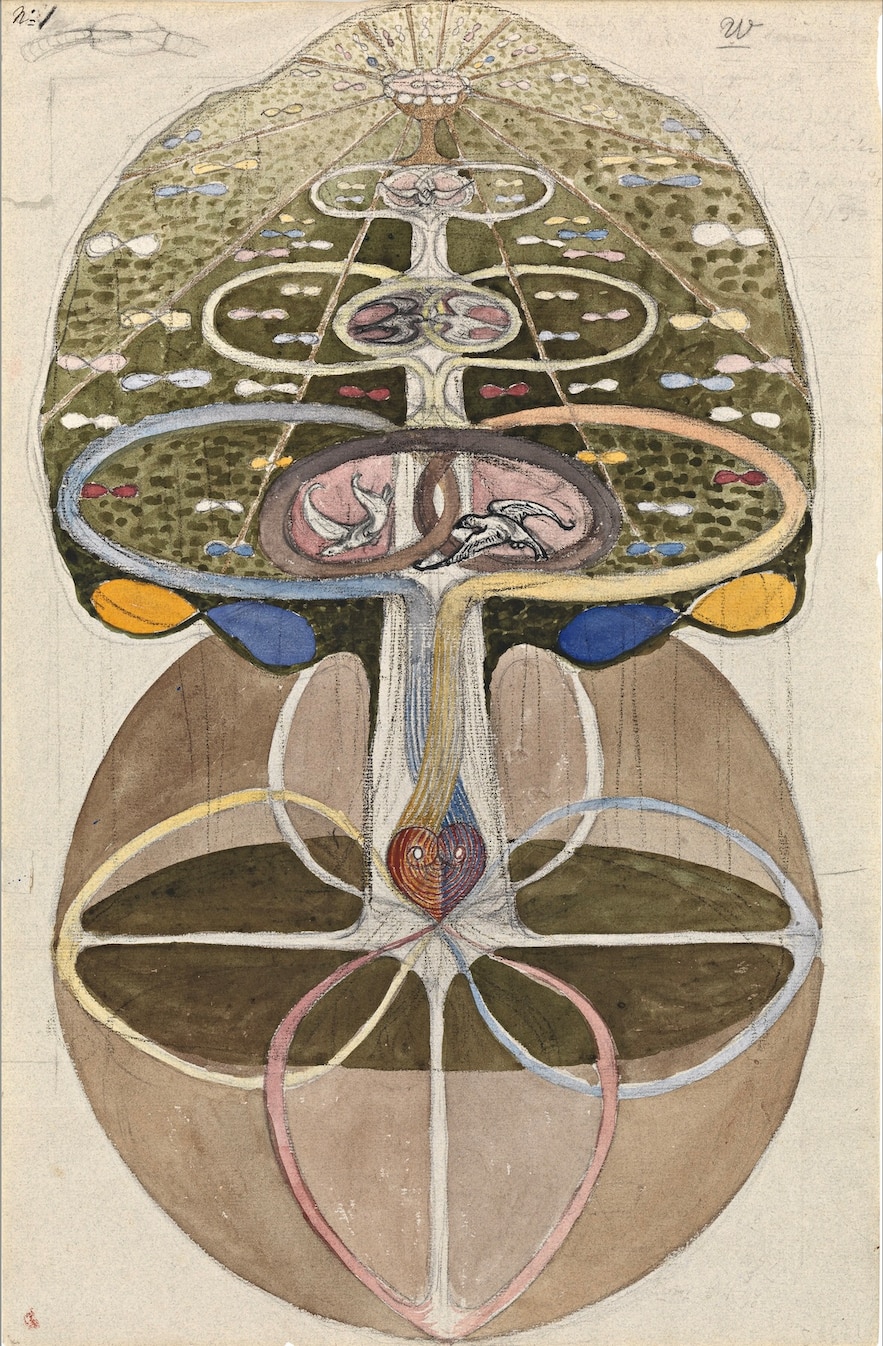

But, from the end of the 19th century, in the shadows, those who devoted themselves to spiritualism, then in vogue, became passionate about theosophy. A feminist before her time, she created the group Les Cinq (from Fem), who practices automatic writing and drawing. It is the spirits, she is convinced, who then dictate to her the creation of her emblematic series, Paintings for the templebegun in 1906 and bringing together 193 compositions. She evokes, in circles of letters and signs, theosophical teachings on the origin of the world and the quest for a lost unity aimed at bringing together opposing forces – good and evil, masculine (yellow) and feminine (blue). .

If this spiritual search is at the heart of his work, we must add his fascination for science, inherited from his father. In 1917, Hilma af Klint produced a series on invisible matter. “Theosophists maintain that the atom can be seen through clairvoyance and for Hilma af Klint, fascinated by the natural world, it is a door to the cosmos,” points out curator Lucia Agirre. In her notebooks, the artist will note that the particle follows a process of development comparable to the spiritual path in which she believes.

“The Tree of Knowledge, Series W, no. 1, 1913.

/ © The Hilma af Klint Foundation, Bilbao 2024

However, just like the geometric compositions steeped in esotericism and the botanically inspired watercolors that followed, these abstract works were only shown to a few initiates during Hilma’s lifetime. The rejection of Templeher major work, by Steiner, the founder of anthroposophy, confirmed the artist’s feelings: the world is not ready to taste the fruits of her reflection, she will therefore reserve the first for the future society. And to facilitate the task of tomorrow’s art historians, she classifies, rolls and carefully stores her paintings in her workshop, out of sight. A winning bet since she is celebrated today on all continents and an imposing foundation bears her name in Stockholm.

.