In the Caillebotte family, the elders for a long time made them swear never, oh never, to deal with museum directors. A shame when we know today the staggering rating of the artist, to whom the Musée d’Orsay will devote, in 2024, a retrospective in collaboration with the Getty Museum in Los Angeles and the Art Institute of Chicago. A shame when we discover the disdain with which the administrators welcomed, in 1894, the bequest laid down by Gustave Caillebotte. This story, precipitated by administrative confusion and political cowardice, is one of the nuggets of Gustave Caillebotte, the unknown impressionist (Fayard), first biography written by his great-grand-niece Stéphanie Chardeau-Botteri.

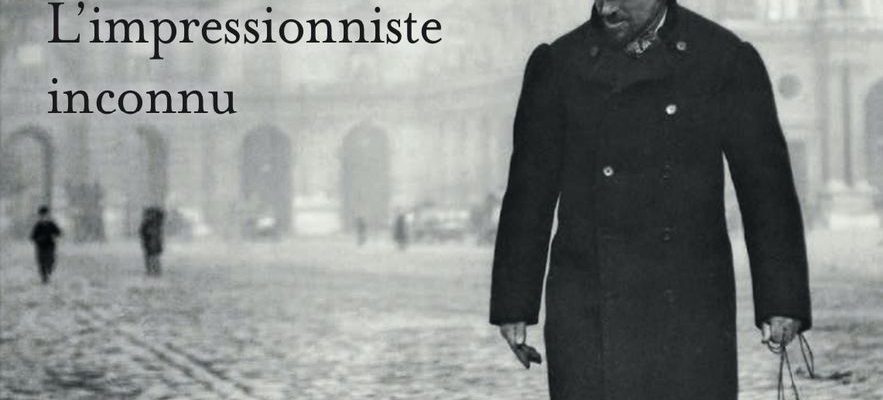

In the apartment of the latter – who is also an expert on the Impressionist painter Armand Guillaumin – Uncle Gustave reigns. On the wall of the dining room, a gigantic photograph of the grandfather, taken by his brother, where we see the artist walking in the rain in the courtyard of the Louvre and seeming to chat with his dog, Bergère. The top-hatted figure engulfs the room; one thinks while admiring her that she continues to observe the family, plunging it into the shadow of her gigantic and tumultuous memory. A posterity that suffered many insults before taking, belatedly, in the 1990s, its rightful place. The Caillebotte family is now large – around 70 people –, divided, partly downright angry and no longer bearing the famous surname.

© / Fayard

Gustave Caillebotte died in 1894, aged 45 and childless, after spending his last years in the arms of a bubbly Charlotte, a concubinage strongly disapproved of in the wealthy Parisian upper middle class to which he belonged. His brother, Albert, a priest, has no descendants. Only Martial has two children: Jean, who died as a young man on the front in 1917, and Geneviève, who extends the family under the name of her husband, Chardeau. Uncle Gustave, worried by the premature death of a second child, René, had written his first will at the age of 28, twice revised until its definitive explicit version, in 1893. The extremely wealthy artist – his father made his fortune thanks to the Société Générale des Lits Militaires – wishes that his entire collection be offered to the State, on the condition that all the works be exhibited at the Musée du Luxembourg, temple of contemporary art in the capital at the end of the 19th century.

A phenomenal collection

Convinced against his time that Impressionism deserves its place in the history of art, he indeed buys the unsold canvases of his painter friends in poverty. To Monet, always with an empty pocket, having his damaged canvases repaired at his own expense, outbidding them when they pass through the Drouot auction room, repaying his debts, lending him a lost fund… To Sisley too, Pissarro, Manet, Degas , Renoir… At the end of his life, he was surrounded by a phenomenal collection.

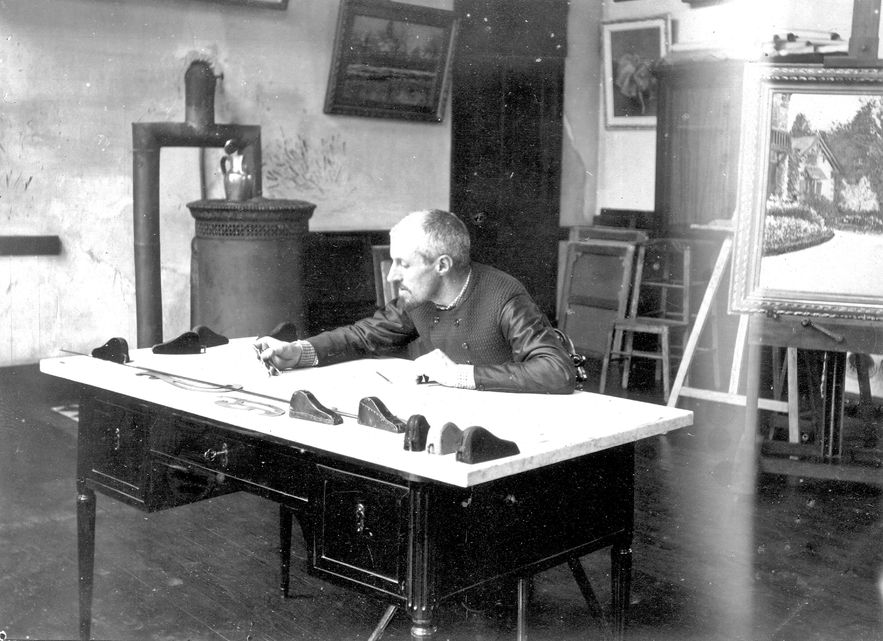

Gustave Caillebotte draws his sailboats. Private collection

© / stephanie chardeau bottieri

As soon as the will was in hand, his brother Martial and his executor, Auguste Renoir, asked a notary to come and list the legacy. “There were some on all the walls, hung tight, even in the bedrooms and locker rooms,” writes Stéphanie Chardeau-Botteri. Two Millets, four Manets, five Cézannes, seven Degas, eight Renoirs, nine Sisleys, sixteen Monets and 18 Pissarros, to which Renoir proposes to add parquet planers, one of the first works of the deceased. And that’s where it all goes downhill. Renoir informs the director of Fine Arts of the windfall, who, against all odds, panics. The civil servant dreams in petto of joining the Academy and tells himself that if he accepts this scandalous legacy, and organizes his exhibition on the picture rails of Luxembourg, the Academicians will hold a grudge against him. He therefore balks, quibbles, quibbles. Agreed for a few works of these unfortunates, but only for “a tolerable number of paintings.”

The press gets involved, partly scandalized by the prospect of seeing these horrors hung, the Institute lets out cries of outrage and the director of the Luxembourg museum, he sculls, embarrassed. After months of controversy, the State reluctantly accepted 38 paintings (the current heart of the Musée d’Orsay) and gave up, with relief, the twenty others, including The Croquet Party, by Bonnard and Bathers at rest, by Cezanne. “Martial Caillebotte was flabbergasted. Ten years after the death of his brother, while the whole world was fighting over the Impressionists, the French State still refused to give these artists the place they deserved”, retains the great-grandmother -niece. Remain in the hands of the family 28 masterpieces and sixty paintings painted by their uncle Gustave.

Without precaution, without supervision, or even insurance

On the death of Martial, his daughter Geneviève inherits. Should she buy a new car? She calls merchants, sells. Does it have to deal with unforeseen work? Rebelote. For a few hundred francs, the collection was scattered over the years 1910-1920, heading for the United States. As for the works of Caillebotte, she does not even offer them. “A Sunday painter”, she believes, in unison with her time which sees in Caillebotte a generous patron much more than an artist. Geneviève’s grandson – Stéphanie’s grandfather – remembers having played in the attic of the family apartment, in the middle of a profusion of upturned frames, which he used as football goals, the ball bouncing good on stretched canvases. Caillebotte misunderstood, despised, his family was then unaware of having such a treasure, and left the polyptych of Giverny, painted by Claude Monet, rolled up against the wall of a caretaker’s house. Geneviève’s sons sell in turn, “to the right, to the left”.

In 1983, for an obscure presentation of works by Caillebotte, the organizers asked the town hall of Yerres, where the Caillebottes had long owned a vacation home, to lend them paintings. The employees of the technical services search in the reserves, put in the back of their van these objects, transported without precaution, without supervision, or even insurance. An anecdote told by Valérie Dupont-Aignan – wife of Nicolas, the former mayor of the city – the director of the Caillebotte house, now renovated and transformed into a museum. Ten years later, 1994, it was the Gustave Caillebotte exhibition at the Grand Palais: suddenly the Sunday painter, the regatta enthusiast, the owner of 32 sailboats, the expensive friend of the Impressionists met with deserved esteem, his rating soared. panics, climbs and explodes. Rue Halévy, 13 million euros at Sotheby’s in 2019; the same year Uphill path, $22 million at Christie’s. Close to the family, Valérie Dupont-Aignan was approached by Laurence des Cars, director of Orsay, who asked her to organize a meeting – she knew that the great-grandnephews still had Boat party. Classified as a national treasure in 2020, this canvas depicting a boater rowing on the Yerres, framed with audacity, will finally be acquired by LVMH for 43 million euros, and will return to Orsay (which could have had it for free in 1894 , if his distant predecessors had not been choosy!).

Culture Minister Rima Abdul-Malak in front of the painting “The Boat Party” by Gustave Caillebotte when entering the Musée d’Orsay on January 30, 2023 in Paris

© / afp.com/Anne-Christine POUJOULAT

And also in 2019, it is The Man on the Balcony reportedly sold for $40 million. The painting, for which Gustave had his brother René pose leaning on a stone balustrade, was composed in the private mansion that their father had built in the 1860s at 77 rue de Miromesnil, a property that has since been sold… and which now houses Nicolas Sarkozy’s offices today. The scene was sketched precisely in the room where the former President works and receives. In the past, the family had asked Valérie Dupont-Aignan to organize a visit to the premises, finally a few separate visits because they bicker a lot. The meeting never happened, yet family disputes, Nicolas Sarkozy knows how to do it.