“He got high on his own cam”, “he talks nonsense, once again”, “a deeply disturbed individual, it is increasingly obvious”, “another elitist with a CV mediocre who mocks with contempt while avoiding the bottom “… On what subject, without a doubt of a burning topicality, were we able to raise these exchanges ofkindnesses in recent weeks between Anglo-Saxon researchers and essayists? On Karl Marx and his posterity.

The object of the crime: a study published in the Journal of Political Economy, a reputable academic publication, on how the author of the Capital has gone mainstream. Its authors, Phillip W. Magness, an economic historian affiliated with the American Institute for Economic Research, a libertarian think tank, and Michael Makovi, a young economist from the University of Northwood (Michigan), wondered what role played the October Revolution in his intellectual posterity. Before 1917, Karl Marx, who had died thirty-four years earlier, exercised, in their own words, only a “modest academic influence”, was an “intellectual figure recognized on occasion but relatively minor”: “Who would fight against this kind of windmill?”, ironically in 1907, at the time of a reissue of the Capitala British scholar.

By immersing oneself in a dozen of the greatest academic journals, we find his name four times less often cited than that of Adam Smith, two times less than that of the British philosopher Herbert Spencer and barely as much as that of the American economist. Henry George, one of his intellectual rivals. Everything changed with the coming to power in Moscow of Lenin and his comrades, which made Marx one of the most quoted intellectuals in the world. A status he has retained, thirty years after the fall of the USSR.

A “synthetic Marx” makes other thinkers

To quantify this phenomenon, the two researchers used Ngram Viewer, a Google tool that allows you to find the frequency of a word or name in a corpus of several million publications. But how to estimate the intellectual influence of Marx in a world where the October revolution would not have taken place? By creating a “synthesis Marx”. From a list of dozens of other names of intellectuals, contemporary or not, socialist or not, Magness and Makovi tested combinations of authors whose average rate of citations, over the years 1878-1916, was turns out to be relatively close to that of Marx: a large piece of Ferdinand Lassalle and a good spoonful of Rodbertus (two other socialist thinkers), a pinch of Nietzsche, a hint of Rousseau…

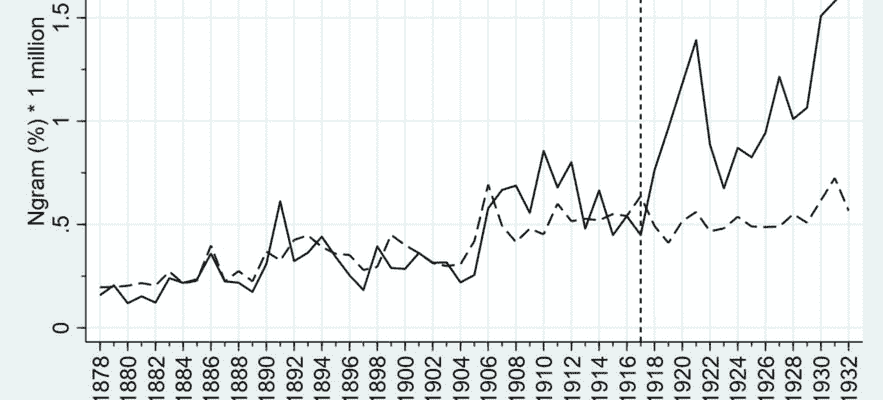

Until 1916, the real Marx and this “synthetic Marx” displayed, quite logically, a close citation rate. After 1917, the quotation of Marx takes off, stabilizes then flies away again from the end of the Russian civil war in 1922, while that of the “Marx of synthesis” remains relatively stable, with three times less quotations approximately. By carrying out additional calculations, the two researchers realize that Marx saw his rating rise in the eyes of non-socialist thinkers as well as socialist thinkers: he distinguished himself from the entire intellectual field. Not only did the coming to power of the Bolsheviks stimulate curiosity about him, but the Soviets themselves fed it with great support from research institutes and reissues of his work.

[Image de la courbe des citations de Marx et du “Marx de synthèse”]

Image of the Marx quotation curve and the “Marx of synthesis” from the article “The Mainstreaming of Marx: Measuring the Effect of the Russian Revolution on Karl Marx’s Influence” (The University of Chicago Press Journals)

© / Image of the Marx quotation curve and the “Marx of synthesis” from the article “The Mainstreaming of Marx: Measuring the Effect of the Russian Revolution on Karl Marx’s Influence” (The University of Chicago Press Journals)

For Magness and Makovi, Marx’s intellectual reputation therefore benefited from an “unforeseen external political shock”, without which his posterity would have been quite different, which places the social sciences more than ever before the challenge of apprehending him in the light of its “inextricable links” with the Soviet experience. What they reaffirm, in a popular text published in mid-November, by emphasizing that Marxist intellectuals want to keep Marx’s “theoretical scheme” without “the violent legacy of Lenin, Stalin, Mao, Pol Pot, Castro”, and by accusing those who criticize them of wanting to “unload the baggage of the legacy of the Soviet Union”.

“Laughable Parochialism”

In itself, the finding of a “boost” given to Marx’s reputation by the events of October 1917 may not seem very new. It was still necessary to quantify this intuition… And that did not prevent the article from triggering, in the days following its publication, a digital trench warfare which probably goes beyond the simple framework of the German philosopher: some of the belligerents were for example already torn apart, in recent years, on the highly debated “1619 project” of the New York Times, which aimed to reassess the impact of slavery on the founding of the United States. Between two personal attacks, Magness and Makovi and their adversaries thus threw themselves back in the face, to defend their respective thesis, the memories of the German politician Karl Kautsky (“Only a handful of people had read The capitallet alone have understood it”) or a eulogy of the influence of Marx by the famous sociologist Max Weber.

The critics of the two researchers accuse them of underestimating the importance, in the dissemination of Marx’s ideas, of the German Social Democratic Party (SPD), which exceeded 20% of the vote in 1890 and reached 35% in 1912. Or judge, like journalist and essayist John Ganz, that their quantitative analysis of his influence from printed quotations reflects a “laughable parochialism” vis-à-vis an author whose objective was not “to obtain tenure in a university or publish in journals “. For the latter, the study does not constitute “a serious exercise in intellectual history” but “a political attack imitating the methods of the social sciences to defend the dogmatic assertion ‘Marx = Soviet crimes'”. A review that prompted a new line from Phillip W. Magness, this time using the work of historian Eric Hobsbawm on the limited circulation of Marx’s work at the turn of the 19th and 20th centuries.

We were there, wondering about the merits and the limits quantitative methods and digital humanities, or to say that social networks are good for the dissemination of social sciences but not always for their image, when the economist Branko Milanovic came to join the game with a more dispassionate analysis. If he agrees with Magness and Makovi on the take-off of Marx’s influence thanks to October 1917, without which it would have been “diluted”, he sees in it a testimony to his “greatness”, in the same way as that of an Adam Smith, a David Ricardo or a John Keynes, whose “we seek in the writings of the explanations with our current evils”. For him, reproaching Marx for not having convinced his contemporaries is equivalent to criticizing Jesus “for having had only a dozen disciples, not having put his ideas on paper nor having applied to join the Academy of Athens or a synagogue in Judea”. An observation signed by the man who, in his latest book translated into French, Global inequalities. The fate of the middle classes, the ultra-rich and equal opportunities (La Découverte, 2021), wonders if we are not slowly returning to a world, “very familiar to any reader of Karl Marx”, where inequalities of wealth within countries will be more visible than those between countries. country.