This is what we call a dialogue of the deaf. Invited onto a TV show just before the legislative elections to clarify the position of a New Popular Front ready to flout European budgetary rules, Marine Tondelier dodges the issue… three times. Instead of clearly answering the question “Are you going to challenge the treaties?”, the national secretary of the Ecologists dodges, preferring to mention Emmanuel Macron’s poor record on public finances, or the fight that the left intends to lead against poverty or for the climate. There is no question of scaring the French or of sending back the image of an unbelievable program. The countries of the eurozone have only just revised – marginally – the famous constraints of the stability pact, after months of difficult negotiations. Furthermore, the Court of Auditors is alarmed by the state of French public finances.

But now that the elections are over, the Greens’ headliner will probably show less modesty. Because in the world of economists, the question of new budgetary rules is being raised with increasing insistence. Not because of the left’s expensive programme, but because of global warming, which could force all European countries to ask for additional financial room for manoeuvre. This is in any case the main idea of a report published by the NGO Finance Watch on Tuesday 16 July. Thierry Philipponnat, its chief economist, explains: “We are entering a world where deficits and public debts will be greater than before. However, the economic and political world is not ready.”

A left-wing speech? The expert, who spent nearly ten years in the upper echelons of the Financial Markets Authority (AMF), does not really have the profile of an environmental activist. “The economic impact of climate change is totally underestimated,” he continues, in an analysis that aims to be outside of political trends. On the one hand, climatologists expect the planet to warm by 3 degrees by the end of the century. This means that entire sections of our society will find themselves in difficulty due to flooding, heat, the effects of the transition on employment, not to mention threats to trade, armed conflicts and waves of migration. However, studies by economists suggest an impact of one or two points of GDP over a fifty-year period. Not really enough to scare decision-makers.

Costs largely underestimated

“Some statements are even exaggeratedly misleading. According to William Nordhaus, Nobel Prize winner in economics in 2018, a temperature increase of between 2.7 and 3.5 degrees would correspond to an optimal level of adaptation for the global economy!” laments Thierry Philipponnat. There would therefore not be much to fear. And humanity could adapt to this warming, with modest investments. This work is now strongly contested. In a recent report, the European Environment Agency lists 33 different risks for the economy, all linked to climate change. Just one of them – rising sea levels – could cost Europe 1,000 billion euros per year, or 6% of the region’s GDP!

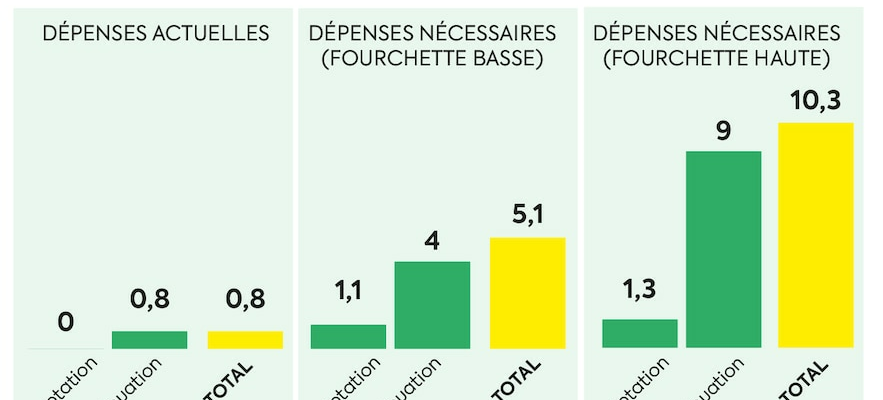

“In France, the Pisani-Mahfouz report puts investment needs at 66 billion euros per year, but this is a low estimate,” adds Clara Leonard, CEO and co-founder of the Avant-garde Institute. “This work does not take into account all the costs linked to climate change: environmental protection, the bill left by the increase in extreme weather events, the cost of research and innovation to try to find technological solutions, financial aid for those who lose out in the transition.”

According to the most precise data to date, the needs for adaptation to and mitigation of climate change within the EU would reach an annual amount of between 800 and 1,600 billion euros, or between 5 and 10% of the GDP of the Old Continent. A gigantic bill. The problem? The private sector will only be able to take on a limited part of it, since many projects linked to the transition are not profitable. Building dikes to protect a city from rising waters or connecting a stadium to the national electricity grid to avoid using generators are useful measures from a climate perspective, but they are expensive and do not generate any turnover. “According to our estimates, the private sector would take charge of around 30% of the necessary investments,” reports Thierry Philipponnat. And even then, the EU would have to benefit from a single capital market allowing innovative companies to raise more funds, as in the United States. But today, the conditions are not right.

3811_INFOG_CLIMATE

© / The Express

Deviating from the famous Maastricht criteria?

“Let’s stop telling ourselves the pretty story about private capital that will take charge of financing the transition,” concludes the chief economist of Finance Watch. Author of a recent report on the future of the single market, the former Italian Prime Minister Enrico Letta also sounds the alarm: “The investments that we have to make are not solely driven by financial considerations.” The implication is that the public sector will have to pay the bulk of the bill, while it is already heavily indebted. How can this be done?

To finance its flagship measures, the New Popular Front is already considering deviating from the famous Maastricht criteria on debt and deficit. This option is also being examined by some economists, with the difference that they are looking beyond an electoral mandate. “The current rules are very restrictive,” acknowledges Jérôme Creel, director of the research department of the French Economic Observatory (OFCE). If a country wants to invest in the ecological transition, it will have to cut even more in other types of spending. This could be health, education, social. I am not sure that this is a good thing, especially in a period when economic activity remains quite weak.” It would therefore be necessary to remove part of the spending from the limits to be respected. “We could say, for example, that we preserve 40% of green spending because it works for the common good. The same goes for spending related to European defense.”

Of course, all this is easier said than done, the expert acknowledges. European countries should agree on the list of strategic investments and convince the most frugal among them to participate in the system. “For the moment this is not an option. We have only just confirmed the current limits – 3% of GDP for the deficit and 60% for the debt. But I am convinced that at some point we will have to reopen these discussions, because everyone will be stuck,” believes Thierry Philipponnat.

“We need safeguards”

Many liberal economists warn of the risks of such a strategy. “We must maintain budgetary constraints,” warns Christian Gollier, Director General of the Toulouse School of Economics. “Before monetary union, a program like that of the New Popular Front would have led to a balance of payments deficit and a devaluation of the currency. Today, this is no longer possible. Within the eurozone, the financial irresponsibility of a State is shared with neighboring countries. We saw this with the Greek debt crisis. All the States bear the economic consequences together. We therefore need safeguards.”

When revising the debt and deficit thresholds, the author of the Climate after the end of the month (PUF, 2019) therefore prefers the idea of an eco-fund carried at the Union level: “It is more transparent than trying to distinguish in the budgets what is green from what is not.” The problem? Here again, it would be necessary to go through a revision of the treaties. Because, in the current situation, Europe cannot show a deficit, and its own resources are limited to 1.4% of GDP. A threshold very insufficient in view of the amounts to be financed for the climate transition.

Europe knows how to mobilize, it has proven it. After the start of the pandemic, it decided on a recovery plan worth an unprecedented 800 billion euros. Why would it not be possible to set up a permanent mechanism to deal with global warming? Once again, the difficulty is political. “This path would require stronger cohesion within the Union. In the United States, the 50 states have long given responsibility for a large part of economic decisions to the federal level. In Europe, we are still very far from this degree of solidarity. Countries have difficulty accepting a right to review their own decisions,” deplores Christian Gollier.

A possible role for central banks

Can the European Central Bank come to the rescue and help finance the transition? This is one of the avenues mentioned in the Finance Watch report. “The monetization of public debt – in other words, the partial or total financing of public deficits by central banks – is prohibited by the Maastricht Treaty. However, it is not a leftist idea. It was implemented massively in the United Kingdom, from the end of the 19th century to the middle of the 20th century, and in the United States from the Greenspan era” (the chairman of the American Federal Reserve from 1987 to 2006), suggests Thierry Philipponnat.

One crucial question remains: is this massive recourse to central banks not likely to create inflation? On this point, opinions differ. “Some tell us that it depends on economic conditions. The lessons of our two thousand years of history seem clear to me, explains Christian Gollier. The surplus of liquidity always ends up pushing up prices, which then seems like a disguised tax for citizens.” Debt specialist and former Treasury official Clara Leonard points out another possibility: “We could imagine advantageous interest rates for banks that refinance themselves at the Central Bank and then invest in green projects.”

The head of the Toulouse School of Economics is arguing more for the development of a “price signal”, embodied by the rise of the carbon market. “Giving a – high – price per tonne of CO2 encourages economic agents to invest in decarbonisation. Which, ultimately, significantly reduces the bill that remains to be paid by States”, specifies Christian Gollier. The revenues from this mechanism can notably finance aid measures for people or sectors suffering from the transition. “Many options are on the table. Our report does not claim to sweep them all away”, acknowledges Thierry Philipponnat. Each of them has its advantages and disadvantages, its supporters and its detractors. Enough to fuel the debate for months, even years. If only the terms are well defined by political leaders.

.