“A lot of people think we’re done with the pandemic stories. But we risk having many more. I know that by saying that, I pass for the bird of bad omen!” Hervé Fleury, virologist and professor emeritus at the CNRS and the University of Bordeaux, is not one to spare his words. For him, the observation is clear: the loss of ground of the Covid-19 pandemic in no way presages the end of the danger posed by viruses. According to him, humanity would even have a great chance of being confronted with it again in the years to come. “There are many factors: there are changes in ecosystems, deforestation, the increase in the number of human beings, the displacement of populations… The plane, too, which is a very important mode of viral transmission”, lists the searcher.

But among this non-exhaustive list, one element is missing: global warming caused by human activity. Several recent studies point in this direction. And one of them, published in August 2022 in the reference journal Nature demonstrates that more than half of human infectious diseases have been aggravated by climatic hazards linked to greenhouse gases, whether it is atmospheric warming, drought, heat waves, forest fires, or even extreme precipitation or floods. Since we must not see the glass completely empty, 16% of infectious diseases have also seen their effects reduced due to these same hazards. But the trend is clear: climate change would indeed increase the spread of infectious diseases.

“More than 75% of pathogens that affect humans are of animal origin”

The main cause is to be found in the increased risk of zoonoses, that is to say diseases transmitted to humans through an animal intermediary. “More than 75% of pathogens that affect humans are of animal origin,” recalls Anna-Bella Failloux, researcher at the Institut Pasteur and head of the arboviruses and insect vectors unit. Obviously, how not to think of the Covid: still today, the most probable explanation for the appearance of the SARS-CoV-2 virus remains that of an animal virus – probably coming from a bat – having been transmitted to humans with or without an intermediary animal.

This is where climate change comes in. Indeed, it should greatly increase the risk of these zoonoses, according to a another study published in the journal Nature, conducted by researchers at Georgetown University in the United States. According to them, at least 15,000 new interspecies transmissions should occur by 2070, according to a scenario of a temperature rise limited to two degrees by then, an already optimistic scenario according to the IPCC.

The cause of this vertiginous increase is to be found in the important flows of mammal migrations which should take place in the coming decades. Due to global warming, more than 3,000 species, in search of viable habitat and food, are expected to move and congregate in certain places on the planet. And it is precisely this crossing of species with very different geographical origins, carrying their own pathogens, which would favor this increase in virus transmission between animals.

Most of these viruses pose no danger to humans. But the study is concerned that the proximity of some of these biodiversity hotspots to very densely populated areas could only heighten the risks of zoonotic transmission. “Yes, climate change will increase contact between humans and species that are reservoirs of pathogens, confirms Hervé Fleury. This is where we will have to look for explanations for the next pandemics.”

The tiger mosquito, a growing danger

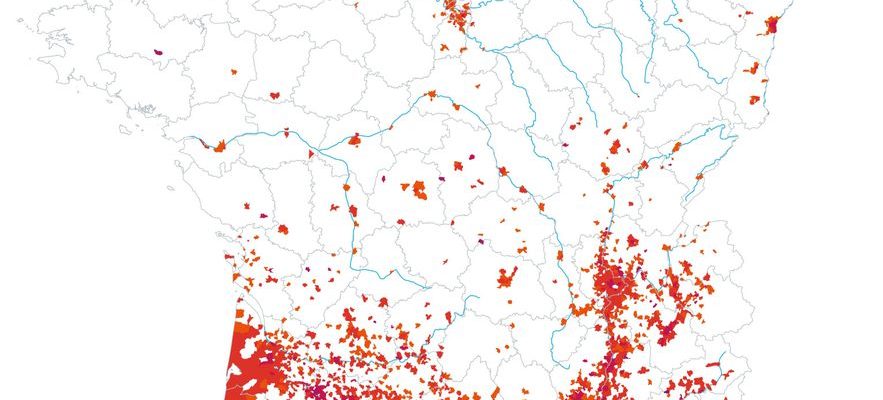

Beyond avian flu carried by migratory birds, another animal is a source of concern for researchers: theaedes albopictus, better known by its more familiar surname, the tiger mosquito. Its progress has been meteoric in mainland France in recent years, so that today it is “one of the ten most invasive species” and “presents one of the greatest risks of viral transmission”, underlines Anna-Bella Failloux. Now present in three quarters of French departments, this tiger mosquito is a vector of particularly dangerous diseases, such as chikungunya, dengue or Zika.

The establishment of the tiger mosquito in metropolitan France

© / afp.com/Valentin RAKOVSKY, Laurence SAUBADU

The appearance in mainland France of this species cannot be attributed to climatic causes, but is mainly linked to maritime and air transport. Nevertheless, its current and future spread bears witness to the impact that a global rise in temperatures in the world can represent. Originally from the tropical climates of Southeast Asia, the tiger mosquito has adapted perfectly to the living conditions of Western Europe.

Moreover, this global temperature increase is even very favorable to the tiger mosquito in many aspects. It allows it to become infectious earlier in its life cycle, and to have a longer period of activity during the year. Finally, the viruses it transmits flourish more above 26°C, a climate that we find longer and longer in the year. A disturbing accumulation.

Large-scale risks

For now, however, the risks of epidemics linked to these emerging infectious diseases remain to be qualified. In 2022, for example, there were 378 cases of dengue in France, including 66 indigenous cases (that is to say via infections by tiger mosquitoes in France, and not abroad). An “exceptional” situation, however, underlines Public Health France, which recalls that the number of indigenous cases in 2022 alone is higher than the period from 2010 to 2021.

But in some parts of the world, some particularly dangerous diseases are already experiencing a very worrying spread. The Global Fund to Fight AIDS, Tuberculosis and Malaria wanted to “sound the alarm” last April on the spread of malaria in Pakistan and Malawi. In question, particularly violent natural disasters that affected these two countries in 2022 – floods in Pakistan, cyclone in Malawi – which caused the stagnation of large quantities of water. An environment suitable for the reproduction of mosquitoes carrying malaria, which has caused an upsurge in the disease, with nearly 1.6 million cases in 2022 in Pakistan alone according to the WHO. “What we have seen is real proof of the consequences of climate change on malaria,” said Peter Sands, President of the Global Fund, last April, adding that “the mechanism by which climate change will ultimately kill people is its impact on infectious diseases.”

“Insufficient understanding of these phenomena”

Because it is ultimately what worries part of the scientific community: the current lack of knowledge on these new emerging diseases and the extent that they could take. “We are obviously going to make progress in the treatment of these new diseases. But we risk experiencing difficult times in the coming decades, because we have an insufficient understanding of these phenomena”, explains Xavier de Lamballerie, virologist at the university. of Aix-Marseille and specialist in emerging diseases.

“Today, I am unable to tell you the exact impact of climate change on these emerging diseases”, recognizes the virologist, also a member of Covars, the new Scientific Council. “If we wonder, for example, about the impact of a one degree rise in temperature on bird migration, we are today unable to make very fine predictions, species by species. In the ten at the next fifteen years, we could have a lot of surprises.” Before concluding, in a weary tone: “We need a lot, a lot more knowledge. And for that, we will have to invest massively in research.” Prevention is better than cure: the adage has perhaps never been better.