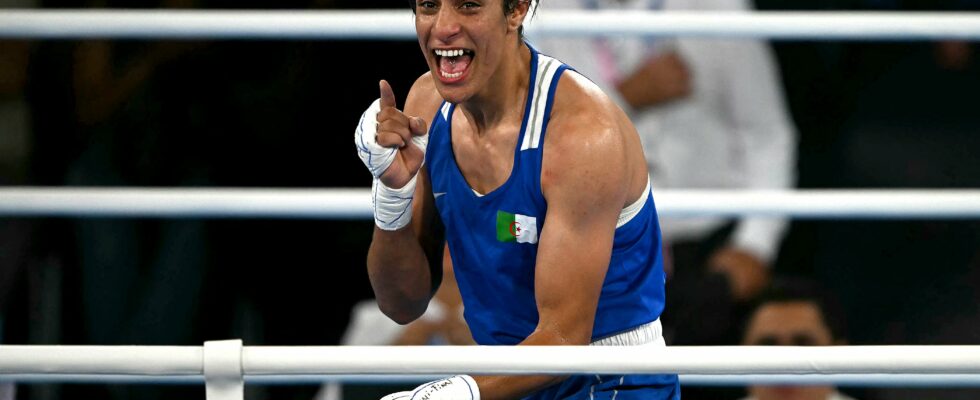

What is a woman? The question seems simple, but the latest controversies surrounding female boxers Imane Khelif (under 66 kilos category) and to a lesser extent Lin Yu-ting (under 57 kilos) have shown that answering it could be very complex. In reality, the definition of the female category has been tearing the world of sport apart since the arrival of female athletes in competitions, a hundred years ago. But the 2024 Olympic Games had everything to make the subject particularly explosive.

This time, it’s not about swimmers or runners, but about boxers: the stakes are therefore not just about fairness between the opponents, but also their safety. This in a context where, in recent years, debates related to sex and gender have become particularly sensitive due to the activism of LGBTQ+ rights activists. Added to this is the war in Ukraine, with Russia certainly delighted that a scandal (stoked by the Russian president of the International Boxing Federation, close to Vladimir Putin) has cast a shadow over the success of the Olympics.

For reasons of fairness related to the different physical abilities of men and women, sports competitions have been organized into two categories since the 1920s and the democratization of women’s sport. “But even today, despite scientific progress, the criteria for establishing who can compete in the women’s category remain variable, relative and subjective with regard to intersex athletes,” notes Julie Mattiussi, lecturer in private law and criminal sciences at the University of Strasbourg, a specialist in personal law, particularly in sport. Surprisingly, these criteria differ according to the disciplines, including at the Olympic Games. They are also at the heart of inextricable debates between doctors, scientists and lawyers, who struggle to agree on a univocal and incontestable framework.

As many definitions as there are federations

First, there is the official sex, the one that is on identity papers. Most often, it is established at birth: a doctor looks at the baby’s physical appearance and indicates its sex on its birth certificate. In France, it is necessarily male or female, and in the very rare cases where it is not possible to determine it, the law gives the medical profession three months to decide – “generally based on the least complicated medical interventions to be implemented later to orient the child’s anatomy towards one of the two sexes”, specifies Julie Mattiussi.

Some international federations do not go further and are content to register athletes in the category, male or female, designated by their civil status. This is the case for basketball, for example. But others have decided to do otherwise, particularly in cases of suspected intersex, by issuing their own rules. Each time a little different, and sometimes even variable over time. World Athletics, the international athletics federation, distinguishes the case of trans and intersex people. Since 2023, the latter must have less than 2.5 nmol of testosterone per liter of blood over twenty-four continuous months. A threshold that was 5 nmol since 2019, and even 10 nmol between 2011 and 2019.

Conversely, World Rugby, the international rugby federation, only asks its athletes not to have suffered the effects of testosterone at puberty in order to be able to register in the women’s category. A scale called “Tanner” establishes the different stages of the body’s transformation during the transition from childhood to adulthood and, after a certain stage, it is no longer possible to be considered a woman. More severe, swimming combines all the rules: not to exceed 2.5 nmol of testosterone per liter of blood permanently, and not to have suffered the effects of testosterone at puberty.

For its part, the International Olympic Committee (IOC) decided… not to decide anything. In 2021, it passed the responsibility for this arbitration back to the federations. A choice indirectly at the origin of the current confusion surrounding Imane Khelif and Lin Yu-ting. Because the boxing federation had made official last year its use of chromosomes to define the women’s category and the exclusion of intersex people carrying male genes (XY), including, in all likelihood, these two boxers. But the IOC, in open conflict with this structure, refused to let it organize the Olympic tournament and took back control. By returning to the passport rule for the definition of the women’s category, reintegrating the two athletes in the process…

Testosterone level, an irrelevant criterion

For Julie Mattiussi, the IOC’s choice should not be seen as a disavowal of the more severe federations. But not as support either. “It can have an influence on the idea of accepting that these women may have biological characteristics that favor them, but no more or less than many men considered exceptional athletes without asking questions about their physical characteristics,” analyzes the lawyer. Because in reality, none of the rules issued to date are really satisfactory in saying who can compete as a woman.

“From a scientific point of view, using testosterone levels to distinguish men from women does not appear to be the most relevant,” says, for example, Claudine Junien, professor emeritus of genetics at the University of Paris Saclay (Versailles Saint-Quentin-en-Yvelines) and author with Nicole Priollaud of It’s your gender that makes the difference. This hormone is certainly known to help produce muscle, speed up recovery or increase motivation, and to be found on average in much higher quantities in males than in females. “But there is no clear cut-off between men and women on this indicator, rather a continuumwith some women whose high testosterone levels are of the same order of magnitude as those of men with the lowest levels,” argues Professor Junien.

Would the use of chromosome analysis be more reliable? For the geneticist, the answer is yes: “From the moment an individual carries the Y chromosome, he or she should not be considered as belonging to the female category, regardless of his or her hormonal status. This chromosome contains about a hundred genes specific to men. Even if their role is not yet fully known, they all contribute to conferring specific characteristics of a male.” But nature loves complications, variations, exceptions.

From science to justice

1% to 2% of births are intersex – that is, hundreds of thousands of individuals each year in the world. And the range of possibilities is immense. Chromosomal variations, with XXY people for example. On the Y chromosome, the “SRY” gene, responsible for the organization of the testicles, can be mutated and prevent the production of testosterone, giving the subject a feminine appearance. Or, other mutations on other genes will give the body resistance to male hormones.

In all these cases, is the presence of a Y chromosome sufficient to give such an advantage that it would justify excluding intersex people from the female category? The scientific data does not, to date, actually allow us to decide. The question, which is highly debated, has therefore been taken to court. The hyperandrogenic South African athlete Caster Semenya, at the heart of the controversy at the World Athletics Championships in Berlin in 2009 after winning the gold medal in the women’s 800 metres and then being banned from competition, has since been fighting to have her rights “recognised”.

The Court of Arbitration for Sport, located in Lausanne, ruled against her, as did the Swiss Federal Court, which serves as the appeals chamber for this instance. But the athlete then appealed to the European Court of Human Rights (ECHR), which declared itself competent: “With four judges against three, the magistrates considered that the discrimination she was the victim of was not sufficiently justified, and more precisely that the review by the Swiss Federal Court had not been sufficiently thorough on this point,” recalls Julie Mattiussi. The story does not end there, because the Swiss government appealed this decision before the Grand Chamber of the ECHR. The hearing took place in May 2024, and the response has not been given to date. Many observers believe that it could declare itself incompetent, to avoid having to rule on this very delicate question.

.