Fatalism, a characteristic of our country: one in three French people considers the country’s decline to be irreversible, according to French Fractures Study of the Jean-Jaurès Foundation published in October 2023. What is surprising in a society where the President of the Republic himself, at the time François Mitterrand, claimed in July 1993 that “in the fight against unemployment, we have tried everything”? The idea that politics cannot influence reality has continued to spread, like a venom paralyzing public action. And yet, a few kilometers from home, peoples of die-hard reformers are still resisting impotence.

The effort first requires a clear, long-term diagnosis: in Italy, Sweden or Canada, it is on the brink of the abyss that governments have developed major reforms, called upon to transform their country from sick to model. Above all, it requires unwavering political will, beyond bureaucracy, lobbies and those who think that any change in practices is impossible. At a time when the new government led by Michel Barnier is highlighting, even in the titles of its ministers, “simplification”, “partnership with the territories”, “food sovereignty” or “academic success”, as so many promises, we can only advise them to take a look at what works elsewhere.

The figure is striking. The French consume 12 times more hypnotics and sedatives than their German neighbors, and 15 times more anxiolytics. Are they 15 times more depressed? Let’s say instead that prescribing practices differ greatly on each side of the Rhine, as does the way in which outpatient care, or “city medicine,” is managed. This is a source of inspiration for France, which is faced with many challenges in maintaining a quality health system without increasing national spending.

Let’s start with a common point between the two countries. Health expenditure is financed by health insurance funds that cover the entire population, without leaving out certain disadvantaged groups, as is the case in the United States. The fact that health insurance funds are much more numerous in Germany, and some are private, has no overall impact on the expenditure of insured persons: the remaining out-of-pocket costs for households remain relatively low (12% on average, compared to 8.9% in France).

It is in the practices of community medicine that the differences accumulate. German doctors employ more healthcare professionals (nurses, health assistants) capable of performing certain medical procedures, in addition to administrative tasks. This reduces the length of appointments in Germany by half (eight minutes) and ultimately allows more patients to be treated. The profession of medical assistant has existed in France since 2019, but few doctors use them. Their training would benefit from being broadened, so that they can, for example, apply dressings, like their German counterparts.

As shown a recent report of the Institute for Research and Documentation in Health Economics (IRDES), French doctors, compared to their German counterparts, are more liberal when it comes to prescribing certain medications. They are not closely monitored, while in Germany, prescriptions are subject to strict control – which encourages them to prescribe generic drugs more often and avoid abuse. And for good reason: German general practitioners and specialists must report to the regional association of doctors to which they belong. They must justify all additional expenses compared to a target budget for their practice, under penalty of sanctions.

…and better paid

© / The Express

In Germany, a “less efficient” hospital system

“The strong point of German community medicine is the involvement of doctors’ associations, which participate in defining budgets, with health insurance funds,” emphasizes Zeynep Or, research director at Irdes. “In France, private doctors do not feel responsible for the health system,” continues the researcher. A decentralization of management, as in Germany, with their involvement in decisions, would be a good thing.” It would make it possible to better define the fair cost of different medical procedures – the last global update dates from 2005 in France – but also to regulate the opening hours of surgeries, to avoid overcrowding emergency services. “But there is still a strong attachment among some French private doctors to having the minimum of constraints,” emphasizes Patrick Hassenteufel, professor at the University of Paris-Saclay, specialist in health policies in Europe.

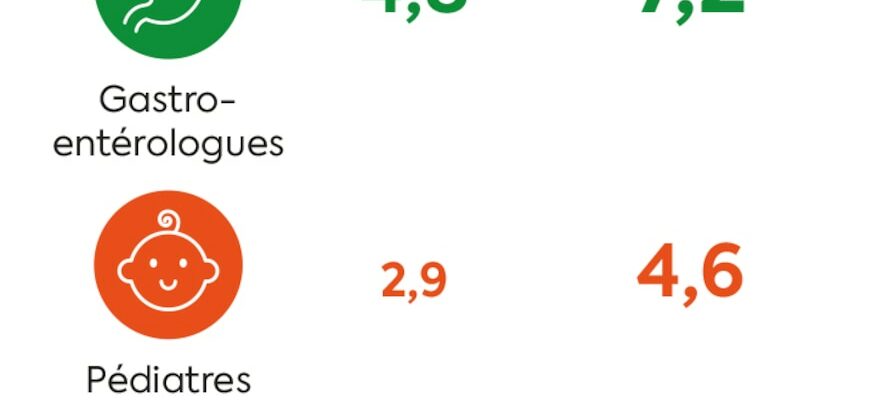

However, not everything is rosy in Germany. Irdes notes that its hospital system is “less efficient” than that of its French neighbor. It still has 4.9 beds per 1,000 inhabitants compared to 2.9 in France. The Minister of Health, Karl Lauterbach, has been carrying out a vast reform to rationalize hospital care for several months. This social democrat wants to develop outpatient surgery (without overnight hospitalization) and reduce the number of operations deemed unnecessary. His goal: fewer beds, in more specialized and therefore higher quality establishments. He also wants to remove hospitals from systematic fee-for-service pricing, which has already been done for care provided by nurses and has allowed their staff to be protected from budgetary constraints. A reform that French hospital workers are looking at with envy.

.