You will also be interested

[EN VIDÉO] 3D brain produced using 3D MRI Using the new IRMa 3D software, a 3D animation can be created from an MRI image. The vivid detail of these animated amplified movements can help identify abnormalities, such as those caused by blockages of spinal fluids, including blood and cerebrospinal fluid in the brain.

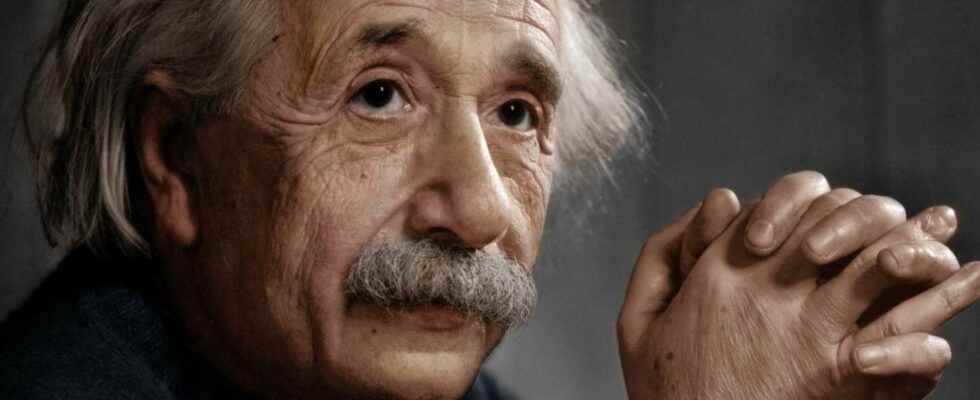

On March 14, 1874, Ulm, Germany, was the birthplace of one of history’s most famous scientists, so much so that his name has become a common word to describe someone gifted: Albert Einstein. If the importance of his scientific work is known to most people, there is a more confidential anecdote about the genius’ brain. Did you know that the matter grayEinstein was stolen by the one who made his autopsy ?

Einstein died at the age of 76 on April 18, 1855 in Princeton Hospital in his sleep at around 1 a.m. The same day, at 8 a.m., his remains were sent to the morgue for an autopsy. It is Thomas Stoltz Harvey who officiates that morning. The 43-year-old doctor cut his teeth at Yale with Harry Zimmermann, a neuropathologist of Lithuanian origin, a pioneer in the study of diseases of the central nervous system. Methodically, he proceeds to the autopsy of Einstein’s body; he feels his viscera, opens his rib cage where his organs are bathed in blood. Cause of death of the greatest genius of the XXand century: aneurysm rupture of the abdominal aorta. The news obviously makes the rounds of newspapers around the world: “ Einstein is dead », title the Daily Princetonian“ Dr. Einstein, father of the bomb, is dead “, can we read on the front page of The Denver Post.

The Stolen Genie’s Brain

Albert Einstein gave very clear instructions about his end of life, ” I want to be cremated, so no one can idolize my bones “. The bones of genius do not interest Thomas Harvey, but his brain does. Following his father’s last wishes to the letter, Albert Einstein’s eldest son, Hans, opposes any organ removal from the remains after autopsy. A last wish flouted twice: by Einstein’s ophthalmologist who stole his eyes, and by Thomas Harvey. In the silence of the Princeton morgue, the pathologist shaves off Einstein’s shaggy hair and scalps him. He removes the scalp of Einstein to unveil his brain cavityand with a surgical saw, he incises it to finally reach thebrain. He carefully detaches the organ from the rest of the body.

Harvey’s first instinct is to weigh the brain ofEinstein. He weighs 1,230 grams, a value a little below the average which is 1,300 grams for an adult man. Harvey takes several shots of the brain and then decides… to cut it into small pieces! 240 to be exact. With the brain pieces preserved in jars filled with formaldehyde in his trunk, Harvey sets off for Philadelphia. The University of Pennsylvania has a rare instrument at that time, a microtome. Like a delicatessen slicer, the microtome makes it possible to make ultra-thin cuts (of the order of micrometer) of frozen or fixed biological tissue. The brain slices are then kept between two slides and can be observed at microscope. Three months of work are necessary for Harvey to make 12 sets of a hundred cups each. Only a few pieces remain intact. Harvey sends sections to his fellow pathologists. A brain as brilliant as his must present singularities and an interest in science.

Thomas Harvey gets down to the methodical analysis of Einstein’s brain and begins writing a report with his observations. He hopes to make an interesting discovery after a year of work. The press is enthusiastic, the New York Times title on April 20, 1955 ” Key clue sought in Einstein’s brain “. The key clue in question is the location of the headquarters of theintelligence, a neurobiological quest started in 1860 with the analysis of the brain of Carl Frederich Gauss, the famous mathematician. On the occasion of this article, the family of Einstein learns of the theft of the brain of the genius of the family. Harvey manages to convince Hans to leave him the samples for the research to continue, which he reluctantly accepts. But Harvey’s analyzes are disappointing. He is not an expert of this organ and the knowledge about the brain of the time do not make it possible to differentiate Einstein’s brain from that of ordinary mortals. It is terribly ordinary. Harvey does not deliver the report to the Einstein Medical Center Philadelphia who had requested it. The results of his peers are also slow to arrive.

The brain found

For more than 20 years, Einstein’s despoiled brain fell into oblivion. No scientific publication about it appears and the disappearance of the organ does not seem to alert anyone. Harvey loses his job at Princeton and takes his notebooks, personal effects and glass jars in his suitcases. He leaves the state and disappears from radar. And then, in 1978, a young 27-year-old journalist, Steven Levy, who cut his teeth at New Jersey Monthly, receives a request strange from its editor: finding Einstein’s brain!

After a long investigation, he finds Harvey in Wichita, Kansas. The last pieces of Einstein’s brain had been there all along, still in their glass jars, tucked away in a box in his office. Levy says, in his article published in August 1978that Harvey showed him the pieces he kept ” the cerebellum of Einstein, a piece of his cerebral cortex and aortic vessels “.

Levy’s article revives research on Einstein’s brain. It is then said that Einstein’s brain has more than neurons than the others, that it presents a particular configuration at the level of the fissure of Sylvius which increases the size of its parietal lobes. Unfortunately, all of these observations are unconvincing and the headquarters of theintelligence remains an abstract concept. The only work that stands out is that of Marian Diamond, a neuroanatomist at the University of California at Berkley. She calculates that Einstein’s brain has a higher ratio of glial cells to neurons than that of the 11 control brains – which we imagine to be less brilliant than that of the physicist. This work was published in 1985 in the journal Neurology. Marian Diamond is at the heart of the latest episode of our podcast Science Hunters ! It is already available to listen to here and on all your favorite listening platforms.

In 1998, Thomas Harvey finally returned the last fragments of Einstein’s brain that he possessed to Eliott Krauss, his successor as pathologist at Princeton. In 2005, for the hundred years of Einstein’s death, the pathologist agrees to return to this incredible story during a series of interviews recorded from his home in New Jersey. He died on April 5, 2007 at the age of 94. Since then, research on intelligence has continued, but without Einstein’s brain, which rests in peace in the Mutter Museum from Philadelphia where the public can observe the microtome cuts made by Thomas Harvey.

In addition to the workshops offered throughout France by the Society of Neurosciences, at the origin of Brain Week, Futura highlights the latest scientific advances concerning our ciboulot. Cognition, psychology or even unusual and extraordinary stories, a collection ofitemsof questions answers and of podcast to be found all this week under the tag ” brain week » and on our social networks!

Interested in what you just read?