Two days in the life of Algeria. This November 1, 2024, the army parades through the streets of Algiers for the 70th anniversary of the war of independence against France. Abdelmadjid Tebboune, the President of the Republic, and Saïd Chengriha, the army chief of staff, are traveling up National Road No. 11 perched side by side in the back of an armored vehicle. To the sound of trumpets and timpani, they each take turns giving the military salute to the crowd. Alter ego as if in perfect harmony. On December 29, 2024, the head of state delivers his traditional annual speech on the state of the Algerian nation before Parliament. Public television cameras focus on the army boss, dressed in civilian clothes for the occasion, sitting opposite the president. Choreography suggesting that after the people’s elected representative, the general is the most important man in the regime. Or the real holder of power.

All the diplomacies of the world are today seeking to understand who, President Tebboune, 79 years old, or General Chengriha, also 79 years old, really governs in Algeria. And surprise, the assessment differs greatly from one expert to another. “That’s the million dollar question!” smiles Riccardo Fabiani, director of the North Africa program at International Crisis Group. By interviewing four former French ambassadors in Algiers, L’Express gathered so many different interpretations on this question. “Those who say they understand everything about the Algerian regime are lying. The Algerians are North Koreans who speak French, the regime is very opaque,” points out a former ambassador. A “black box”, of which it is “very complicated to understand the core of the reactor”, says Hamid Arab, publishing director of the journal The Morning of Algeriaestablished in France. At the Quai d’Orsay, there is talk of a “conclave of cardinals”. No one would hold most of the power, the bits of power would be distributed between the components of what a current French minister privately describes as a “junta”. The only certainty, repeated by everyone: everything happens elsewhere than in government.

On July 3, 2020, Saïd Chengriha assumed the position of chief of staff of the army which he had occupied for six months on an interim basis, after the brutal death of the very powerful Ahmed Gaïd Salah, his predecessor for fifteen years. But he does not become Deputy Minister of Defense, as “AGS” was. Experts see this as a sign that the army is returning to the barracks, far from civilian power, especially since the discreet “Tcheng”, as he is nicknamed in the army, claims neither charisma nor political role. Trained at Saint-Cyr, a pillar of anti-Islamist repression during the 1990s, the general patiently climbed the military ranks, only becoming noticed through certain violently anti-Moroccan outbursts.

Tebboune, the link

Ideal configuration also for Tebboune, elected with the cumbersome sponsorship of Gaïd Salah, and now free to make his mark. Alas, the president’s reign turns into co-management with the army. In Tebboune the speeches, in Chengriha the hand on the “deep state”. The two new masters of Algeria agree to remove the heaviest symbols of the Bouteflika-Gaïd Salah years. One of them, General Wassini Bouazza, arrived from the DGSI, Algerian internal intelligence. He will be sentenced to sixteen years in prison for illicit enrichment. General Nabil Benazouz, head of the Central Directorate of Army Security, also went from the height of his power to detention in a few months. Even in innocuous outings, to cut the ribbon at an inauguration or launch work on a hospital, Abdelmadjid Tebboune appears flanked by “Tcheng”, a duo of septuagenarians ruling with an iron fist over a country where two-thirds of the population is under 30 years old.

An alliance does not prevent warnings. In September 2024, President Tebboune was triumphantly re-elected with officially 94.65% of the votes, a score corrected to 84.3% a week later. A twisted move by the army, diplomats from the Quai d’Orsay assess, the officers having wanted to show, by a double caricatured maneuver, that they retain control of the ballot boxes and would be able to discredit the head of state as they wish. A sham message already suggested on May 8, 2024, when Abdelmadjid Tebboune went to the Ministry of Defense. In Algeria, the President of the Republic combines his functions with those of Minister of Defense, the trip should not be an event. General Chengriha organizes a welcome with fanfare, with a red carpet, “as if to show the head of state that he is playing outside”, interprets an Algerian entrepreneur who has long been in court in Algiers.

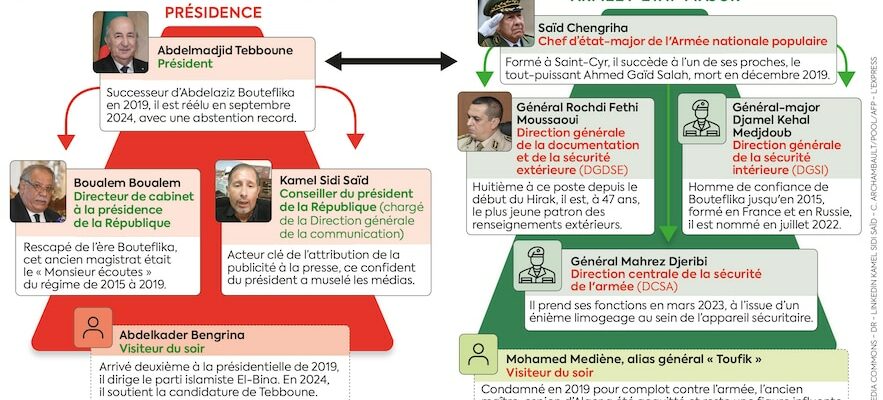

The key men of a two-headed regime.

© / The Express

On several occasions, President Tebboune has shown that he is more than just a frontman. His political rise, from his years as wali, including prefect, after the Algerian ENA, during the dark decade of the 1990s, to his first experiences as minister, bears the mark of skill. Spotted by both the army and the Bouteflika clan, he was bombarded as Prime Minister in May 2017. His anti-corruption speeches then led to a lightning disgrace, less than three months later. Officially, the former senior civil servant was dismissed because of his personal ambitions… and for having gone to France to meet Edouard Philippe, without the approval of his superiors. Hirak, this Algerian pro-democracy movement which emerged in February 2019, puts this Francophile scholar, “better knowledgeable of French politics than the diplomats of the Quai d’Orsay”, into the game, says a former ambassador. When “AGS” forced Abdelaziz Bouteflika to resign on April 2, 2019, Tebboune appeared as the link between the Algeria of the 2000s and that of Hirak.

“Justice by telephone”

At the El Mouradia palace, “Uncle Tebboune”, as some of the youth nicknamed him, pushed his margins of maneuver. He who entertains with his vacation spots – one year, he stayed a few days in Moldova – calls one of his old friends, the magistrate Boualem Boualem, to his side, first as justice advisor, then as cabinet director. In a country where political disgraces often lead to the resurgence of a “case”, then an indictment, his past as boss of telephone tapping, from 2015 to 2019, commands respect. The influence attributed to him reveals some of the failings of the regime. Even certain figures at the Quai d’Orsay imagine him to have information on General Chengriha. Within French diplomacy, he is also said to be involved in what experts call “justice by telephone”, that is to say the submission of magistrates to the ukazes of political power. It is still claimed that he is the real mastermind of the presidential palace, enough to explain the recent obsession against France, Boualem Boualem being presented as “violently anti-French” by a ministerial advisor of the Bayrou government.

“Secular Muslim” and lover of good wines, according to a former ambassador, Tebboune is also deepening the dialogue with the essential Islamist lobby. The Islamo-populist Abdelkader Bengrina, second in the 2019 presidential election, has become a frequent evening visitor to El Mouradia, his El-Bina party has participated in the government since 2021. Cultural and educational policies are inspired by his designs. Rochdi Fethi Moussaoui, the new director of the DGSE, foreign intelligence, is also one of his trusted men: before being assigned to Paris, he was stationed in Berlin in 2020, where he supervised the hospitalization of the head of the State, affected by Covid, for two months.

But the Algerian intelligence services no longer have the authority of the Bouteflika years, when they formed the third major center of power. All-powerful in Saïd Bouteflika’s entourage, the oligarchs also now walk in the shadows. In July 2024, Tebboune signed a decree allowing active officers to lead state companies and administrations. A colonel now heads the mobile telephone operator, Mobilis. “This is a completely unprecedented fact. The army has certainly always exercised tutelary power over the political life of the country, but it reigned without governing. Today, it also wants to administer,” notes academic Ali Bensaad, refugee In France.

“The real decision-makers…”

However, Saïd Chengriha still seems to be consumed by internal struggles. Around sixty generals are now imprisoned; among them, many followers of Ahmed Gaïd Salah. “You don’t know the real decision-makers, neither do I,” a former Prime Minister even told us a few months ago. Among these hidden networks, that, it seems, of Colonel Chafik Mesbah, former intelligence executive, once security and “reserved affairs” advisor to President Tebboune. Several French diplomats have also noticed the sudden return to favor of those close to General Toufik, emblematic boss of all the secret services between 1990 and 2015. Aged 85, Toufik continues to receive evenings in his Algiers residence; General Chengriha himself would seek to accommodate his benevolence.

In addition to Western Sahara, the refusal of the Brics to accept their candidacy in 2023 constituted a serious diplomatic snub for this aging regime, leading to a stormy meeting in El Mouradia during which Tebboune threatened Chengriha to leave. In this decaying atmosphere, the repression of opponents is a rare subject of agreement. Faced with the deaf discontent of a part of the population, a final enemy acts as a glue between the ruling clans: France. In May 2023, a few weeks before the disavowal of Brics, Tebboune had a verse of the Algerian national anthem reinstated, to general satisfaction. In particular, we sing: “O France! The day has come when you must be held accountable.” This is what the Hirak activists demanded from the Algerian elites.

.