Germany and the United Kingdom have just given us the example of two diametrically opposed policies regarding the regulation of drug use. The first has just legalized the consumption of cannabis, while the second, after having banned nitrous oxide (laughing gas), plans to ban tobacco to all people born from 2009. And you, on which side do you lean?

What these two countries and all others lack is a rational approach to drug regulation. We all know that they can cause damage, both to the health of their users and, through the impact they have on their behavior (drunk driving, violence), to the rest of society. . But we all also know that not all substances have the same level of danger, and that it would undoubtedly be illusory, even excessively restrictive and perhaps even counterproductive, to ban them all.

“Magic mushrooms”, less dangerous than alcohol

A rational policy would therefore imply first of all rigorously evaluating the damage caused by different drugs and thus classifying them on a scale from the most to the least harmful, then adjusting the regulation of substances according to their position on the this scale. Depending on whether we give more priority to public health or individual freedom, depending on whether we lean more towards paternalism or liberalism, everyone will have their own opinion on the measures to associate with each level of dangerousness, and this would be an opportunity for an interesting democratic debate. But everyone should be able to agree that good policy should be consistent with each drug’s position on the dangerousness scale.

It turns out that rigorous assessments of drug harm already exist. They were carried out by panels of experts from all disciplines and medical specialties UK in 2010, at the European level in 2015, in Australia in 2019 and in New Zealand in 2023. Taking into account all the physical, psychological and social damage caused by drugs to both users and other people, they gave very consistent results in broad terms.

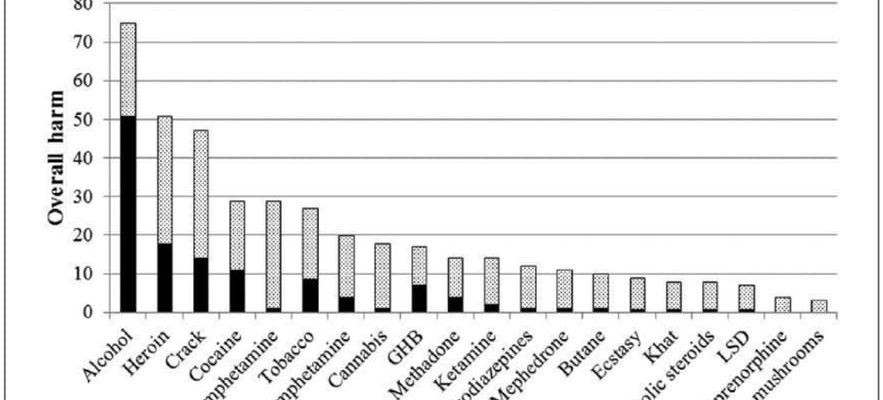

In particular, they agree on the following points: the product that causes the most harm in all categories is alcohol. Tobacco also causes significant damage, more significant than cannabis for example. And many substances currently illegal in most countries, including cannabis, LSD, and ecstasy, cause much less harm than legal products such as alcohol and tobacco.

Results of the European study assessing the damage caused by drugs to users and society. In black: damage to others (violence, accident). In gray: damage to users. Drugs, from left to right: alcohol, heroin, crack, cocaine, methamphetamine, tobacco, amphetamine, cannabis, GHB, methadone, ketamine, benzodiazepines, mepherone, butane, ecstasy, khat, anabolic steroids, LSD, buprenorphine and “magic mushrooms “.

© / Van Amsterdam et al. (2015)/J. of Psychopharmacology

Note that such a classification does not dictate a single policy. For example, it does not fully anticipate what would happen if drug regulations changed. Indeed, while the assessment of the damage caused to users is assessed at the individual level, the assessment of the damage caused to others depends on the prevalence of use of each substance, and would therefore be likely to be revised upwards or downwards in the event of a change in prevalence. Furthermore, the specific characteristics of each product (for example intravenous injections) may suggest measures (such as the distribution of single-use syringes to limit the transmission of infections) which cannot be deduced from the position in the ranking alone.

More generally, regulatory policies are likely to vary both the use and the dangerousness of each product, and therefore the assessment of damages should strive to be dynamic and anticipate the effects of the policies envisaged. However, these evaluations clearly show the extent to which our policies are inconsistent, in the sense that the regulations in place are not at all proportionate to the dangerousness of the substances.

Alcohol, a cultural exception? “A chauvinistic point of view”

The acceptance of alcohol and tobacco and the prohibition of other substances in our society are obviously a historical heritage: the first two have been used in Europe for a very long time, while the other products appeared more recently. At the individual level, the reasoning we hold about drugs is mainly aimed at justifying our own behavior: we tend to consider as acceptable – or even as not being drugs – those which are familiar to us and which we consume, even if we know the associated risks, because we know them and we appreciate the benefits. We are quicker to condemn products that we do not consume, since we see the harm without reaping the benefits.

Some will defend an exception concerning alcohol by praising the contribution of wine to French culture and gastronomy. But it cannot be denied that this is a chauvinistic point of view. Everyone sees culture at their doorstep. Others have the right to be more sensitive to the cultural heritage of tobacco, cannabis or coca. We can also consider that the pleasure that a drug provides can be appreciated for what it is, without looking for a cultural alibi. Who am I to impose on others to only be entitled to substances that I find good according to my subjective criteria? If we claim to be cultural, then let’s not impose our cultural preferences on others. If we claim public health, then let’s be consistent with the scale of the damage.

If, like the UK Government, you are in favor of banning tobacco, then to be more consistent than this Government, you should also be in favor of banning alcohol. If on the other hand you are against the banning of alcohol, then to be consistent you should also be against the banning of drugs less dangerous than alcohol.

On the other hand, legalizing drugs should not lead to the renunciation of other means of reducing their consumption as much as possible, and in a manner proportionate to the damage they inflict. From this point of view, rather than prejudging that the consumption and dangerousness of drugs decrease the more the repression is severe, a coherent policy must also take into account the results of research rigorously evaluating the effects of different policies at the both on the use of drugs and on their dangerousness.