Last spring, the CEO of an American conglomerate of digital platforms asked Sundar Pichai, the boss of Google, if he was able to reconstruct the functioning of generative AI. No, he replied in substance, we don’t know how to do it, we can’t yet trace the source of a series of texts or photographs that made it possible to generate ex nihilo a press article, or an image. It was less than six months ago. In other words, an eternity in the infernal rhythm of artificial intelligence. Today, operators are engaged in a race to try to dismantle, as much as possible, the internal mechanics of the major language models, LLMs. They are spurred on by the prospect of countless trials as much as by the desire of American and European regulators to put an end to the systematic pillaging of works.

The complexity of LLMs is expressed in two dimensions: the volume of data ingested to “understand” the world, and the number of parameters, which are the meshes of the sieve allowing models to interpret this data to develop new creations, a unpublished text or a synthetic image. Count several billion for the first and around a billion for the second. Penetrating these patterns is generally considered an impossible task. Find hundreds of photographs from all origins used to create a synthetic image in a database of 6 or 10 billion works accumulated by companies like MidJourney, SLABOr Stable Diffusion is deemed technically out of reach; even more to reconstruct the percentage of each original image used in the artificial creation.

Find the images that inspired the AI

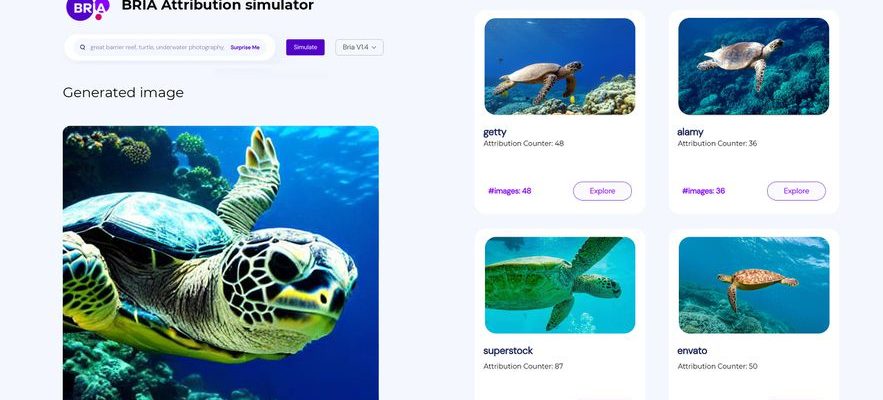

An Israeli company appears to have been the first to solve this problem: Bria AI, has developed an attribution model making it possible to trace the multiple sources of a computer-generated image and identify the hundreds of original works from which it was inspired. When, from Tel Aviv, Yair Adato, CEO and co-founder of the start-up, demonstrates his platform, everything seems simple: he generates an image with a simple “prompt”, or a descriptive sentence, for example: ” close-up of a sea turtle on a coral background. Then, he clicks on “attribution” to launch the machine to trace the process, in this case countless sequences of computer code. The algorithm then reveals (see below) that of the hundreds of images at the origin of the synthesis, 48 came from Getty, 36 from Alamy, 87 from Superstock, etc.

Bria AI’s tool helps identify which photos helped artificial intelligence generate a summary visual.

© / Bria

To explain how Bria AI does this, Yair Adato invokes concepts such as latent mathematical spaces which make it possible to represent certain hidden characteristics in a dataset. “To simplify, the algorithm goes back the mathematical path taken by the proprietary LLM that Bria developed to create images,” summarizes Paul Melcher, a specialist in digital images based in New York, also a consultant to Bria AI. The technology makes it possible to precisely find the origin of an image used in a composite creation. It therefore opens the way to the remuneration of rights holders, at least for the most important contributors.

As with all technological developments, it now remains to generalize the system. Because currently, the image attribution process is limited to the private perimeter of Bria AI. Unlike operators like MidJourney or DALL-E who have indiscriminately collected billions of public domain images as well as copyrighted works, Bria has built its visual inventory solely through commercial agreements with well-known providers such as Getty. , Envato, or Alamy. With (still) 700 million images, its stock is nine times smaller than the German public database LAION-5B which is the benchmark in the sector. But it is clean, assures Yair Adato: no risk of violating copyrights by using protected works, this is the guarantee that Bria offers to its clients.

This ethical precaution is also a limitation: today, if we submit an image generated by MidJourney to the Bria attributor, it will only go back to its own suppliers; It is therefore impossible to reconstruct the components of a news image for example – unless major information agencies like Agence France-Presse, Associated Press, or Reuters followed the path opened by Getty (already a partner of AFP ) and made a deal with Bria to entrust her with their millions of photos. In any case, regulators can now rely on the fact that effective allocation technologies do indeed exist. It would therefore be enough for the American and European authorities to impose the use of these devices to put an end to most of the technological opacity invoked by the large generative AI operators.