A year ago, almost a few days ago, Dick Fosbury died, the first athlete to dare to do a back roll jump in an international competition. It was in the fall of 1968, at the Olympic Games in Mexico, that the American crossed the high jump bar while looking at the sky in front of a crowd that was as stunned as it was enthusiastic. On the Franciscaines picture rails, in Deauville, the contact sheets from the time of the photographer Robert Legros, from the newspaper The Team, break down, second by second, the gesture of the person who will thus win the test and become, despite himself, a libertarian symbol across the Atlantic, like the hippie generation. The Fosbury-flop is one of the eight sporting gestures explored by the essayist and writer Thierry Grillet, former director of cultural dissemination at the BnF. “A new philosophy is creeping into jumping. In tune with the times, the athlete shows the way: no longer setting the bar, but setting the stars. Preferring the verticality of the dream to the horizontality of the competition”, he advances.

Here, the curator opens up more funereal perspectives to the gesture by comparing the photos of Legros with the triptych Pursuit by Vladimir Velickovic. In the 1970s, the Serbian artist, based in France, was inspired by the work of the British Eadweard Muybridge who, in the last decades of the 19th century, was, with the Frenchman Etienne-Jules Marey, the pioneer of chronophotography, a technique allowing rapid movements to be observed in humans or animals by dissociating them. The three paintings painted in black and white, pierced with a few scarlet spots, Pursuit show an athlete stalked by rats trying to escape until, defeated, falling into nothingness. “For me, the color black and white, similar to the photos of Muybridge – with the red of violence – means the race, the pursuit, the fall,” explained Velickovic before his death in 2019.

It is still in the invaluable archives of The Team that Thierry Grillet unearthed this photograph of Allen Meany taken in 1920, which shows the perfect execution of a dive during the women’s event at the Antwerp Olympics. At the time, the Scandinavian model, which requires the diver-gymnast, definitely took over the English concept of the diver-swimmer. The “Swedish” jump, better known today as the angel’s jump, becomes the “seraphic gesture” par excellence. But hasn’t it always been? The ancient diver on the funerary fresco discovered in Paestum, Italy, seems to embody him in the final phase of his angel’s leap, as if voluptuously extending his arms to the deceased. Closer to us, it is Yves Klein, who, in his photomontage of Jump into the void from 1960, throws himself, in street clothes and arms crossed, from a pillar towards the asphalt, to reach the depths of color: “To paint space, I must go into this very space. “

David Hockney, “Olympische Spiele München”, 1972.

/ © National Sports Museum

About ten years later, David Hockney traced the contours of his famous diver on a poster intended to promote the Munich Games in 1972. The British artist, then based in California, was already known for celebrating swimming pools, notably eroticizing the swimmer’s gesture, through his series of Splash, where only the final splash remains of the bodies after penetration into the water. A reversal of the codes on this poster which reveals the bust and head of the athlete at the moment when his hands are about to cut through the waves, the reflections of his skin joining the bluish undulations of the surface.

“Sculptural gesture”

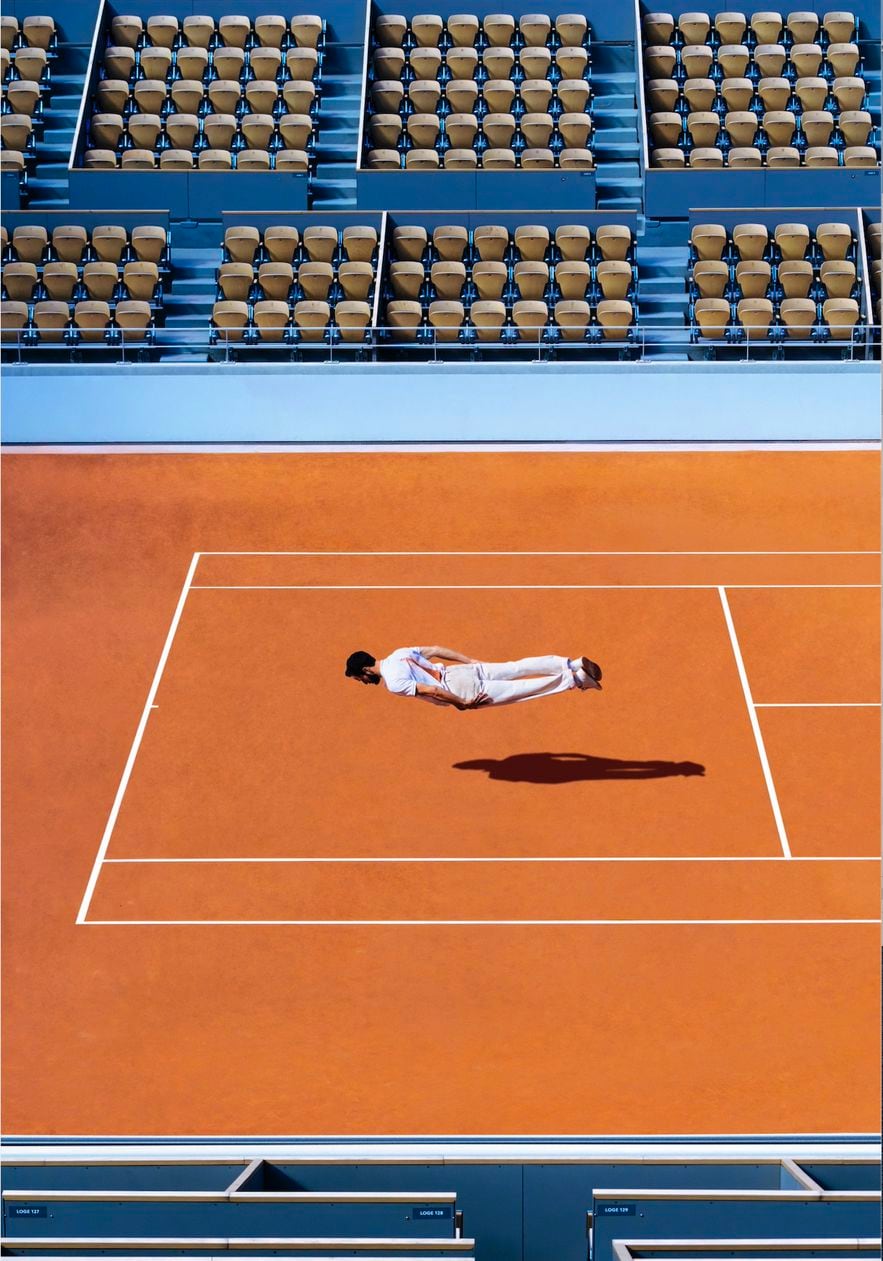

In tennis a different story plays out. That of the “sculptural gesture” symbolized by the “service”, a unique and predictable blow which, depending on its effect, limits the exchange to itself or extends it to infinity. Suzanne Lenglen or Serena Williams on the courts, René Lacoste in his bible published in 1928, Jacques Tati on the screen (Monsieur Hulot’s Holidays), the Nabi Maurice Denis or the precursor of pop art Charles Lapicque on the canvas… Everyone has seized the racket to dissect it or sublimate it. Without forgetting the nice wink of this tennis section with a work by Mathieu Forget, alias Forgetmat. The son of Guy Forget – ace in his time -, who embraced a career as a professional tennis player, before becoming a dancer and photographer, depicts himself levitating on the central Philippe-Chatrier at Rolland-Garros, in a perfect parallelism with the ground, to, he says, make the emblematic stadium “a sort of painted, geometric canvas, a memory of Mondrian, where even the body slips like a line on a red background”.

Forgetmat, “ACE / Roland Garros” (detail), 2022.

/ © Forgetmat

Archery, finally, clearly distinguishes itself from other disciplines by being limited to a single gesture uniting man and tool in a physical and technical fusion, the paradox of which is to be based on immobility. Thierry Grillet describes it as a “philosophical gesture”, because it refers to the Zen wisdom of kyudo, the chivalrous art of archery which takes up the precept of the Stoics: one must aim for virtue as the ideal target (skopos)but the important thing is the goal (telos) – strive to be virtuous. At the beginning of the 20th century, Bourdelle, Rodin’s gifted student, preferred to exalt the power of the archer by drawing inspiration from the twelve labors of Heracles. His athlete, who bends with all his muscles an archer without string or arrow, seems to embody effort and will, the two breasts of sport.

Léo Caillard, “Neon Discobolus”, 2017.

/ © Artist’s collection

These sporting gestures, to which are added here the panenka in football, the touch in rugby, the stride of runners or the “jab” of boxers, are explored both in their documentary part and in their dreamlike dimension, thanks to the works of art which extend the archival documents… At the opening of the exhibition, the Neon Discobolus by Léo Caillard, dated 2017, can summarize them all by offering a timeless vision of what constitutes the essence of sport: tension. The artist, who, since the 2010s, has brought past and present into dialogue in his sculptures, puts a contemporary spin on Discobolus by Myron, a masterpiece of ancient statuary dating back to the 5th century BC. Between reconstituted marble, resin and backlighting technique, its disc thrower embodies this reproduction over the millennia of an eternally repeated gesture.

.