A team of researchers from the Faculty of Medicine of Clermont-Ferrand, in conjunction with Inserm, carried out a rather surprising experiment: making guinea pigs listen to music! Indeed, these rodents have an auditory system close to that of humans.

The 90 little animals were treated to an anthology of songs by the singer Adèle, with a sound level of 102 dBA (used to measure environmental noise and the sound pressure level, editor’s note), the limit authorized by law in the theaters.

But for some of them, the music had been changed to drastically reduce the gaps between loud and quiet sounds to just 3 dB.

After four hours of exposure, ENT tests showed that the auditory system had not been damaged, but that the group of guinea pigs exposed to the modified music suffered from extreme auditory fatigue. Understand that their brain was no longer able to effectively trigger muscles in the middle ear to protect against loud sounds, which is called the stapedius reflex.

The experience was mentioned by Professor Paul Avan, director of the Center for Research and Innovation in Human Audiology (CERIAH), as part of the UNESCO sound week. You can follow his speech in the video below.

Tests show that guinea pigs exposed to modified music failed to fully recover after seven days in quiet (their recovery rate is only 70%). This can be a problem if they are exposed to loud sounds again, as the middle ear muscles will not be able to protect them. Admittedly, the study is still in its infancy, but it reveals the problems that this type of sound modification can cause.

In his presentation, Paul Avan talks about music “supercharged” (or supercompressed, if we want to respect the canons of the French language), but the term compression is ambiguous. Indeed, there are two types of compression in today’s digital music: compression by reduction of the dynamic range, in other words the reduction of the difference between the softest sounds and the loudest sounds, and compression by reduction of the dynamic range. the amount of data.

Compression to save space

Digital sound can take up a lot of space, count, for example, 1.4 MB per second for a traditional audio CD. This is why compression intervenes to save space in terms of storage or to allow distribution with an appropriate bit rate. Most of the time, this compression requires deleting data (lossy), as is the case for AAC or MP3 codecs.

In these cases, the compression eliminates frequencies which are not well perceived by the human ear, for example beyond 15 kHz, or frequencies which are masked by other stronger ones in the sound.

This method is applied at the expense of sound quality. The more you compress, the more information you lose and the more the quality degrades compared to the original. It is therefore necessary to carefully choose the compression rate that is applied so that the differences are not too great between the compressed version and the original version of the music.

Compression to increase perceived sound level

Another form of compression first appeared on radio stations and in television commercials. The goal is to generate a louder sound, without increasing the overall volume. For this, a compressor will increase the soft sounds, or even decrease the loud sounds, so that they are at the same level of intensity. When listening, the music will thus seem louder, which will make it more receptive for the listener.

This practice was then applied to CD audio from the 90s. Sound engineers started by increasing the volume to approach the limits of the media as much as possible, then turned to compression to provide “big sound”. to the listener. For example, CDs from (What’s the Story) Morning Glory?, of Oasis, and Californication, Red Hot Chili Peppers suffer from very high dynamic range compression. This practice therefore does not only concern the music that we listen to in the discotheque, such as for example the title Crank It Up, by David Guetta.

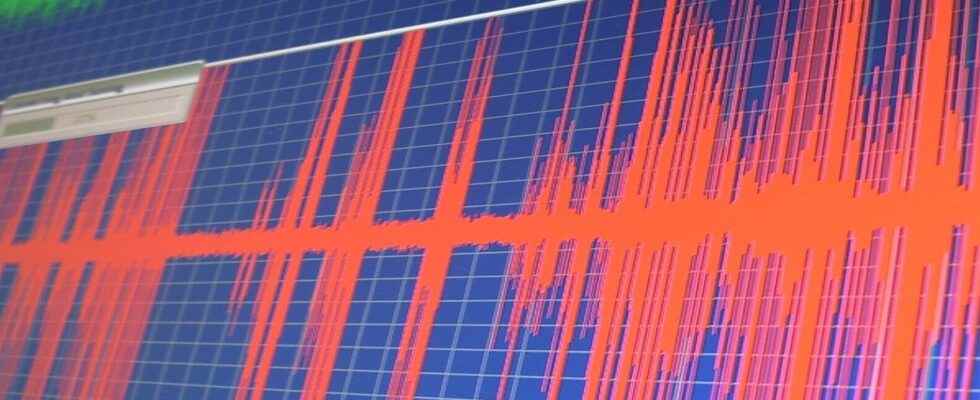

Another representative example is the album Death Magnetic, from Metallica. In the image below, the top two tracks correspond to an extract from the CD version. We can see that during almost the entire song, the level is often at its maximum and the weak sounds are not very present.

On the other hand, the two bottom tracks are much more airy and the level is not pushed to the maximum. This is the same excerpt, but from the video game Guitar Hero III. Admittedly, we’re talking about a metal band here, but that doesn’t prevent us from having nuances in the sound. Conversely, the CD of Random Access Memories, by Daft Punk, uses very little compression, which contributes to its sound quality thanks, among other things, to excellent dynamics.

The volume war hurts the listener

The systematic use of compression has led to a real volume war (Loudness war in English), also called volume race. The video below shows how compression is applied to a Paul McCartney song, and the devastating effects of it.

The only advantage of this type of compression is to be able to hear the music perfectly in noisy places, such as discos or public transport, since weak sounds hardly exist anymore. But the disadvantage is twofold.

First of all, we lose the nuances that contribute to the quality of the music. Fortunately, this process is not used for classical music, because it would amount to no longer making a distinction between the pianissimo and fortissimo passages intended by the composer.

But above all, this method of production leads to brain fatigue that cannot rest during quieter times. During the 2010 edition of Sound Week, Patrick Arthaud, president of the Syndicat des audioprothésistes français, already warned listeners : “We bring in too much information and we drive the auditory system into overdrive. Auditory fatigue is certain. »

Faced with the abuse of compression, audiophiles began to organize and a website lets you know the dynamic range of audio CDs from your favorite artists. Others even attempt to reinvigorate sonically abysmal albums, such as Oasis, as seen in the first two lines in the image below (click to enlarge).

On the streaming services side, an algorithm is applied when listening so that all the songs in a playlist have the same sound level felt by the listener.

For this, they use a normalized index called LUFS (Loudness Units relative to Full Scale) or LKFS. This index takes into account not only signal strength, but also human perception. Each song then undergoes a normalization (increase or reduction in overall volume) during the broadcast, in order to meet the desired LUFS index. This index depends on the streaming service:

- Spotify : -14 dB LUFS (Premium users can opt in the app for -23 dB if they are in a quiet environment or -11 dB for noisy environments)

- AppleMusic : -16dB LUFS

- Amazon Music : -9 to -13 dB LUFS

- Youtube : -14 dB LUFS

- SoundCloud : -8 to -13 dB LUFS

- Tidal : -14 dB or -18 dB (for AirPlay) LUFS

The numbers here are negative because they indicate a reduction from the maximum volume level.

According to the website Wise Audio, Amazon Music does not increase the volume of a song if it is too low. This is also the case for Tidal and YouTube. During normalization, the streaming service ensures that an increase in volume does not exceed the maximum possible level, but does not influence the dynamics. So a heavily compressed song originally won’t be any better.

Also see video:

Christian Hugonnet, founder of the Semaine du son, evokes for his part the launch of a scientific reflection with Ircam and the Hearing Institute, of which Paul Avan is a member.

The acoustics engineer specifies that the record company Universal has expressed its interest in this work. The objective is to create a sound quality label for music albums, guaranteeing reasonable compression. Let’s hope that artists, producers and sound engineers in the future prioritize the quality of sound, rather than its power.