Around ten men in sandals, dressed in traditional Yemeni loincloths, rifles on their shoulders, joyfully begin a war dance on the deck of a large cargo ship. Teenagers with growing beards take selfies in front of an azure sea. Children have fun trampling on Israeli and American flags, in front of tags like “long live the Al-Qassam brigades” – the armed branch of Palestinian Hamas. These scenes take place on the Galaxy Leader, a boat boarded on the Red Sea on November 19 by Yemen’s Houthis, and transformed into a tourist attraction for the local population, off the port of Hodeida. It constitutes the most important war capture since, in mid-October, these rebel fighters targeted commercial ships in the Bab-el-Mandeb Strait, to show their support for the Palestinians in Gaza, in the name of the “axis of resistance” led by Tehran. More than thirty attacks, according to the American army, via drones and missiles.

These repeated offensives have suddenly brought to the forefront a conflict that has lasted for more than a decade: several thousand fighters, the Houthis, supporters of the Al-Houthi clan, today led by Abdel Malek al-Houthi, have been in control since 2014. a significant part of Yemen, the northwest (including the capital Sanaa and the port of Hodeida), where approximately two-thirds of the population live. The civil war left several hundred thousand dead, leading to economic collapse and famine. Facing the Houthis, supported by Tehran, are the loyalist forces of elected President Hadi, supported by Riyadh and brought to power after the Yemeni revolution of 2011.

As proven by the instrumentalization of Galaxy Leader, the support shown in Gaza is also a question of internal politics for the rebels. “They need to strengthen their national legitimacy,” explains Bernard Haykel, researcher at Princeton University and specialist in the Middle East. “The movement, made up of Zaydi Muslims, a branch of Shiism, in a predominantly Sunni country, is a very small minority – 5 to 10% of the population. The only way to gain popularity is to wage war against America, Israel and to defend anti-imperialism.”

The United States drawn into war

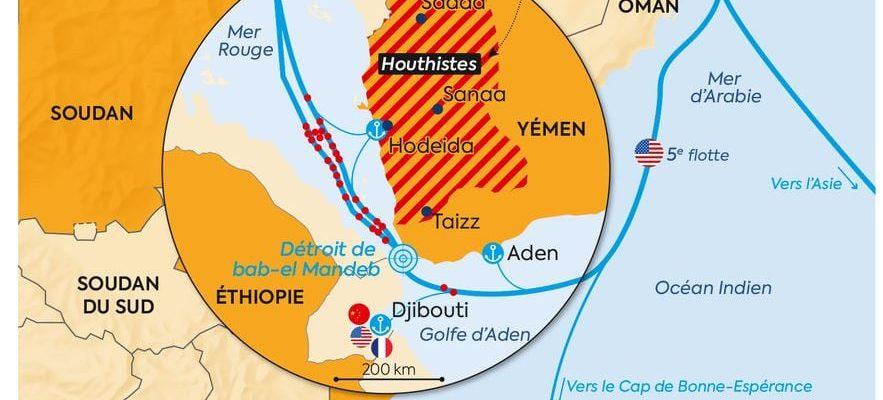

The Red Sea has thus become an additional but powerful war zone in the conflict between Israel and Hamas. With major economic impacts for the entire planet, because the passage, which leads to the Suez Canal, sees 40% of container traffic and 12% of global traffic. The attacks forced shipowners to reroute ships towards the Cape of Good Hope, extending transport time by around ten days and almost doubling its cost. These troubles also increase the price of insurance policies and are likely to disrupt commercial traffic in many ports.

The Red Sea, a new battlefield.

© / Legends Cartography

After maritime responses from the international naval coalition formed by the West in mid-December, the Americans and the British finally decided on January 11 to directly bomb the Houthi positions on site in Yemen. “The strikes were more or less expected, but until now there had been a logic of caution on the part of the Americans in order to avoid direct confrontation,” explains David Rigoulet-Roze, associate researcher at the Institute of Relations. international and strategic (Iris). “The Americans considered that the red line had been crossed on January 9 with the launch of a wave of 21 shots (18 drones and 3 missiles) targeting not only commercial ships but also military buildings present to protect maritime traffic “, specifies the co-director of the work The Red Sea: desires and rivalries over a strategic space (L’Harmattan, 2022).

In fact, the Houthi question is beginning to drag the United States into the war in the Middle East. According to Bernard Haykel, a specialist in the region, the Saudis are staying away for fear of reprisals, while pushing for large-scale American involvement. Riyadh has been negotiating a permanent ceasefire with the rebels since the summer – after its rapprochement with Tehran last March. Which could give the West negotiating leverage: the promise of a permanent ceasefire – and a generous financial settlement – could weigh in the balance. For the moment, despite the American-British strikes, the supporters of Abdel Malek al-Houthi do not seem to want to back down and are on the contrary becoming emboldened: on January 14, a cruise missile targeted an American destroyer, theUSS Laboonoperating in the southern Red Sea.

“The novelty of the current crisis is these non-state actors who possess state means – missiles, drones – and the capacity to strike the sea from land,” observes Maxence Brischoux, author of Geopolitics of the seas (PUF, 2023). “After the American intervention, the shipowners will be the justices of the peace: it is up to them to assess whether the passage seems sufficiently secure. At first glance, not yet,” adds the researcher associated with the Thucydides Center. Of all the contested maritime spaces, the Red Sea has a more mythical dimension, through its link to the Suez Canal.

“A place where anything can happen”

The writer Patrice Franceschi, at the origin of the reissue of Secrets of the Red Sea (Adventure Points, 2023) by the famous adventurer Henry de Monfreid, knows the Bab El-Mandeb Strait well, on which he sailed: “When we pass through it, especially when we arrive via the Gulf of Oman, we have the feeling that we enter a place where anything can happen, for good or bad. For ten years and the start of tensions in Yemen, with the involvement of the Iranians, the Saudis, etc., the Red Sea has found itself at the heart of the globalized war that is currently taking place.” The navigator highlights the difficulty of ensuring security there. “We would need boats on all sides. It is too big to do it with the sole support of new technologies, drones and satellites. To secure the sea, we must strike on land.”

The Americans and the British understood this well. Will this be enough? Because behind the Houthis looms the shadow of the Islamic Republic of Iran. “This sequence is part of the strategy of the “proxies” – Hamas, Hezbollah, militias in Syria and Iraq – launched to put pressure on the United States, Saudi Arabia, the West, Israel…”, recalls Bernard Haykel. “The Iranians do not have a navy capable of directly confronting the US Navy but they have the capacity to cause nuisance and disrupt maritime flows. We are in a hybrid war logic,” explains David Rigoulet-Roze. The Iranians have a spy ship on site, the Behshad, which probably transfers information useful for the identification of ships, says the researcher. “The rebels are at the head of an extensive and extraordinary arsenal given their power, which is also made available free of charge by the Iranians,” adds Fabian Hinz, researcher at the International Institute for Strategic Studies (IISS) and specialist in armament. The vast majority of the missile systems they possess today, both anti-ship and surface-to-surface, are of Iranian origin.”

While Hezbollah and Iran have been relatively measured since October 7, for fear of Israeli or American reprisals, the Houthis can more easily assume the role of disruptive agents. Even if they are masters of their operational decisions, they do not act alone. The solution to the Red Sea crisis therefore lies – at least partially – in Tehran. “So far, the Iranians have shown themselves to be rational, and they seemed to do everything to avoid a direct confrontation with the United States,” underlines Bernard Haykel, but “they want to show that in addition to the Strait of Hormuz, At the entrance to the Persian Gulf, they can block Bab-El-Mandeb and Suez: the three strategic choke points in the Middle East are therefore effectively under Iranian control. In the current crisis, the Iranians aim to secure their regime while gaining popularity by attacking Israel and America. The Houthis’ fight is far from only concerning Palestine.

.