Fatalism, a characteristic of our country: one in three French people considers the country’s decline to be irreversible, according to French Fractures Study of the Jean-Jaurès Foundation published in October 2023. What is surprising in a society where the President of the Republic himself, at the time François Mitterrand, claimed in July 1993 that “in the fight against unemployment, we have tried everything”? The idea that politics cannot influence reality has continued to spread, like a venom paralyzing public action. And yet, a few kilometers from home, peoples of die-hard reformers are still resisting impotence.

The effort first requires a clear, long-term diagnosis: in Italy, Sweden or Canada, it is on the brink of the abyss that governments have developed major reforms, called upon to transform their country from sick to model. Above all, it requires unwavering political will, beyond bureaucracy, lobbies and those who think that any change in practices is impossible. At a time when the new government led by Michel Barnier highlights, even in the titles of its ministers, “simplification”, “partnership with the territories”, “food sovereignty” or “academic success”, as so many promises, we can only advise them to take a look at what works elsewhere.

By the time of the 1993 federal election, Canadians were concerned about the exploding debt. And rightly so: the country had lost its AAA rating a year earlier, and a third of government revenues went to interest on the debt. “Canadians understood that this situation could not continue and that change was coming,” says Jake Fuss, director of fiscal studies at the liberal think tank Fraser Institute.

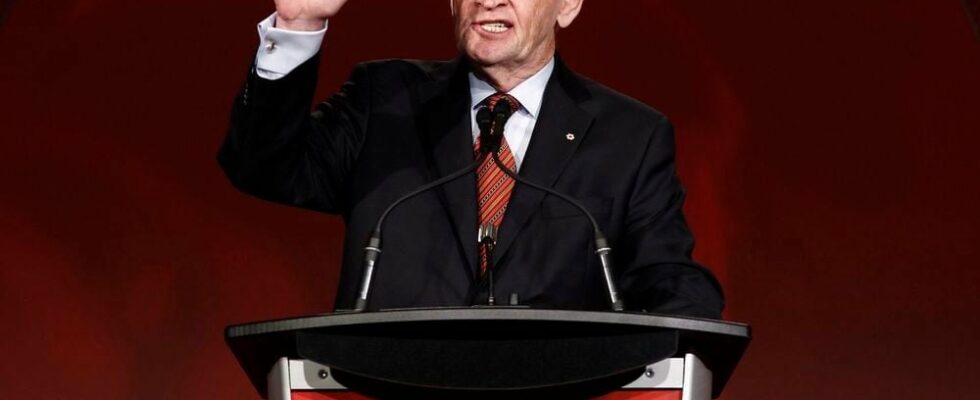

Reducing the deficit, close to 5% of GDP in 1993, is a leitmotif among all political parties. It is finally Jean Chrétien, candidate of the Liberal Party, who convinces the voters with his plan of fiscal discipline, set out in a small red book modestly entitled Creating OpportunityFaced with the threat of a debt crisis, the new Prime Minister knew that he could not be satisfied with cosmetic changes. In 1994, he began a major reform of the civil service called the “Program Review”.

To determine the extent of the budget cuts, his plan calls for six questions to be asked of the various ministries, such as “Does the activity in question continue to serve the public interest?” or “What activities or programs are […] could be transferred […] to the private or voluntary sector?” The answers should make it possible to more precisely target the measures to be put in place. “Instead of saying “find me 5% or 10% savings”, we gave a clear roadmap that made it possible to cut expenses based on precise criteria. That was the key to success,” analyzes Geneviève Tellier, professor of public finance at the University of Ottawa.

In five years, public finances were transformed. The deficit became a distant memory, giving way to a decade of budget surpluses from 1997. “Even after having achieved a surplus, the government remained disciplined on public accounts. This allowed spending to be revived at the end of the 1990s, but in a moderate manner,” explains Jake Fuss. The share of debt in GDP declined each year between 1997 and 2007, thanks to this rationalization effort.

“We are repeating the mistakes of the 1970s”

Of course, these reforms come at a price. Nearly 50,000 jobs in the federal civil service – or 14% of the workforce – disappeared between 1995 and 1999. This drop resulted, in particular, from an incentive for early retirement. But also from the privatization of “Crown companies” – until then controlled by the State – which led to the transfer of civil service positions to the private sector.

The ministries are affected unevenly by the budget cuts. “The Ministry of Industry, for example, saw 30% of its spending cut between 1994 and 1998 with the elimination of many business subsidies, while the Ministry of Transport saw its spending shrink by almost 70%, particularly with the privatization of airports,” explains Geneviève Tellier. The provinces, responsible for health and education services, are also suffering a sharp drop in the transfers they receive from the federal government. Funding for social housing is also decreasing, a choice whose repercussions are still visible today, notes the academic.

This did not prevent Canadians from returning the Liberal Party to power until 2003. Thirty years after the wave of reforms, the “Chrétien consensus” seems to have eroded. The arrival of Justin Trudeau in government in 2015 tipped the country into the opposite direction and spending is on the rise again. “With the 2008 crisis, the population wanted a more active state in the economy. Many Canadians probably don’t remember what was done in the 1990s,” laments Jake Fuss. “We are repeating the mistakes of the 1970s that led to the crisis of the 1990s.” Nothing is ever a given.

.