The image had never been seen since the start of the war. On December 3, Kiev forces released video of a Ukrainian flag flying from the top of a crane on the Russian-occupied east bank of the Dnieper River. “It was hoisted by the fighters of the special unit ‘Carlson’ and will become a bridgehead for the liberation of the left bank of the Kherson region!”, Proud on Telegram the group at the origin of the operation. A few days earlier, the Ukrainian army had already reported skirmishes on the Kinbourne Peninsula, a thin stretch of land in Russian hands at the mouth of the Dnieper.

Since the reconquest of the city of Kherson in mid-November, Ukraine has multiplied the raids on the other side of this river which today acts as a new demarcation line, in the south of the country. What augur a landing, in order to continue the counter-offensive further east? “Crossing this river would clearly not be easy insofar as the Russian army firmly holds the other bank, tempers François Heisbourg, special adviser at the Foundation for Strategic Research. Among all the military operations that the Ukrainians could consider, this would probably be the most difficult.” Moreover, since the destruction of the last bridges which connected the two banks during the Russian withdrawal from Kherson.

high risk maneuver

The geography specific to this river constitutes a first obstacle. A veritable natural barrier, the Dnieper divides Ukraine over more than 1,500 kilometers and can reach, in places, a width of about twenty kilometers. Crossing it on a large scale would represent a much more complex puzzle than the few temporary incursions carried out by boat by commandos.

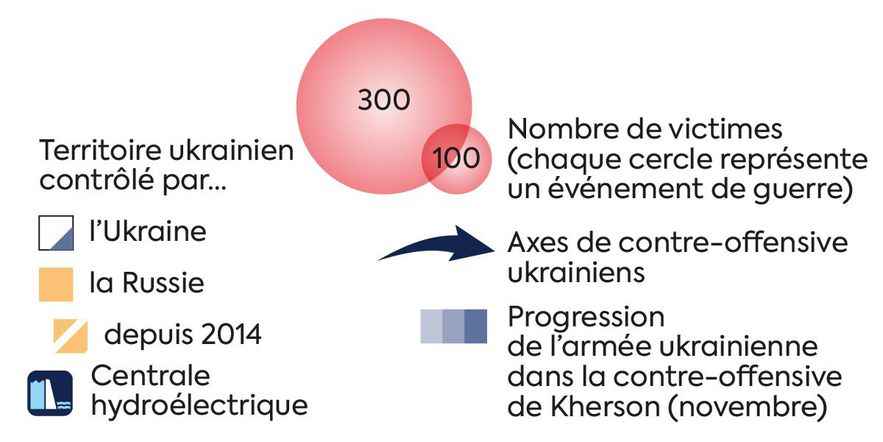

Map

© / Dario Ingiusto / L’Express

Infographics

© / Dario Ingiusto / L’Express

“This very high-intensity operation would require the simultaneous deployment of several pontoon bridges with the aim of transporting as quickly as possible a maximum of infantry and armored vehicles to the other side of the bank, details General (2S) Jérôme Pellistrandi, editor in chief of the National Defense Review. At the same time, the Ukrainian army would have to manage to destroy all the enemy artillery, to prevent its installations from being targeted.

In fact, crossing a river is one of the most delicate military maneuvers, requiring extremely meticulous preparation. Last May, the Russians broke their teeth there during their attempt to cross the Donets River – much narrower than the Dnieper – in the east of the country. Caught under Ukrainian artillery fire, the Russian forces concentrated on the banks of the river had recorded the loss of nearly 80 armored vehicles and 485 men (dead and wounded).

“In this type of operation, we place ourselves in a situation of great vulnerability: the pontoon bridge is by nature immobile and constitutes a prime target, points out former Admiral Pascal Ausseur, now Director General of the Mediterranean Foundation for “strategic studies. When the enemy obtains the GPS coordinates of the bridge, he can destroy it and derail the operation.” To limit the risk of enemy bombardments, the amphibious assault should therefore be accompanied by extensive anti-aircraft and artillery cover.

Terrestrial Alternative

To deter any crossing, the Russian army has taken care in recent weeks to fortify its positions along the entire east bank of the river. Satellite images revealed that it had multiplied the trenches and lines of “dragons’ teeth”, pyramid-shaped concrete blocks supposed to prevent the progress of tanks. “Given the current balance of power, it seems to me that crossing the river would place the Ukrainian forces in a situation of vulnerability too strong to be considered by the Ukrainian general staff”, gauges Admiral Ausseur.

This could, in the eyes of the experts, opt for alternative solutions. One of the most obvious would be to break through the Russian defenses east of the Dnieper, along the front line stretching between the left bank of the river and the Donbass. “In this area, the Ukrainian forces could launch a more classic land offensive, the objective of which would be to descend south to the Sea of Azov, outlines General Pellistrandi. This would have the double advantage of avoiding a landing dangerous and to split in two the Russian forces engaged in the south of the country.”

If successful, the maneuver would also cut the last major rail supply line of the Russian forces present west of this axis. “They would find themselves isolated and with their backs to the river, agrees Admiral Ausseur. Their only logistical line with Russia would be that passing through the Crimean bridge.”