Withdrawal of Western forces, strengthening of Moscow’s influence by Wagner forces, and even expansion of the Russo-Ukrainian conflict: the Sahel has been the breeding ground for major geopolitical struggles for several years, which are played out behind the scenes, from the fight against jihadist groups to successive coups d’état. But a newcomer is now preparing to complicate the equation even further. Viktor Orban’s unpredictable Hungary plans to send 200 soldiers to Chad soon, an unprecedented mission for the central European country.

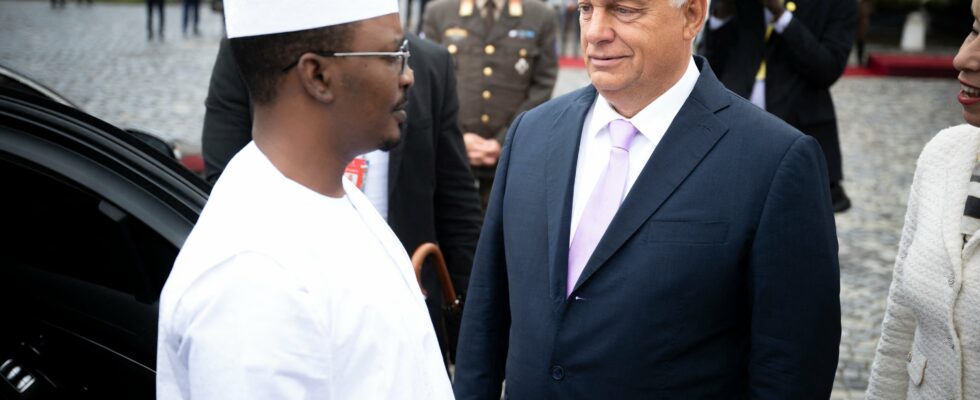

Symbol of this rapprochement, Chadian President Mahamat Idriss Déby Itno arrived this weekend in Budapest and new talks are taking place this Monday with the Hungarian Prime Minister. According to the latter, “Chad is a key country in the fight against immigration” as well as against terrorism and over the past year, Hungary, a member of NATO, has significantly deepened its relations with N’Djamena. It has opened a humanitarian aid center and a diplomatic representation, while signing agreements in agriculture and education. It has also planned to deploy troops to train local forces against jihadists.

“Test mission”

Historically not very present in Africa, the country has developed an all-out diplomacy under the leadership of Viktor Orban, moving closer to Moscow, Beijing and even Central Asia. It has also been eyeing the Sahel for years, where it wants to play “a more active military role” to gain experience, Viktor Marsai, director of the Institute for Migration Research based in Budapest, told AFP.

Since the end of NATO’s mission in Afghanistan in 2021, “the Hungarian army no longer has a theatre of operations where it can sharpen its weapons in a reasonably risky environment,” he says. Hungary initially wanted to join the French-led Takuba task force in Mali, but this grouping of European special forces fizzled out. Its plans in Niger also fell through after a coup in July 2023.

Until the sudden announcement last fall of this mission in Chad, which surprised experts. It will be the first time that she “will have to organize everything alone”, notes Viktor Marsai, evoking a challenge for the country of 9.6 million inhabitants. “It will be a test to see if the Hungarian forces are up to the task”.

Partner of the EU… or of Moscow?

Especially since France plans to drastically reduce its presence in West and Central Africa after bitter disappointments. Chad, a poor and landlocked state of 18 million inhabitants, is the last in the Sahel to host its soldiers, while French forces were driven out by the juntas that came to power in Mali, Burkina Faso and Niger, in particular to the benefit of the new Russian partner. The last American soldiers also left Niamey last August.

In the region, however, several countries are hosting paramilitary forces resulting from the reorganization of the Wagner group. In this troubled geopolitical context, the fear has emerged that Budapest is acting on behalf of Russia, while Viktor Orban met Vladimir Putin again at the beginning of July, provoking the anger of his European partners. And Hungary had to refute “representing the interests of Moscow or any other foreign interest”, through the voice of its special envoy to the Sahel, Laszlo Mathé.

Despite its disagreements with Budapest, the EU “welcomed” its new ambitions, because it is “important that more international partners work with Chad”, a spokesperson for the European Commission in Brussels told AFP.

The opaque role of Viktor Orban’s son

But in Hungary, criticism is flying. First, on the role played by Gaspar Orban, 32, the only son of the Hungarian Prime Minister. After a brief career as a football player in his father’s favorite club, he finally converted to the army. A graduate of the elite British Military Academy Sandhurst in 2021 and promoted to captain in the Hungarian army, in circumstances that have widely questioned in the country, this former missionary in Africa discreetly participated in the negotiations in N’Djamena, according to an investigation by the newspaper The World and the Hungarian investigation site Direkt36published in early 2024.

These secret visits, only spotted by screenshots of videos posted on Facebook and other social networks, fuel suspicions about the real intentions of Viktor Orban and his son in the region.

Faced with accusations of nepotism, the government has for its part highlighted the “expertise and linguistic knowledge” of Orban junior, now officially named “liaison agent to help prepare the mission in Chad”. The effectiveness of such a project is also questionable, with the opposition denouncing a useless “waste of money” and a “dangerous” operation.

Even within the army, some have doubts. In reality, “we don’t know what we’re going to do there,” a retired high-ranking military official told AFP, on condition of anonymity. And then, how will 200 men make a difference in such a vast country, knowing that a third will have to stay at the base camp, he says. Enough to suggest that Viktor Orban’s plan is perhaps not so much to sustainably support Chad as to show the world – and especially its detractors – a posture of international power.