World War II was the greatest war to date. The war began with the German invasion of Poland in September 1939 and ended in 1945.

Tens of millions of people lost their lives in the war, and millions more had to leave their homes.

The Soviet Union was part of the alliance that defeated Nazi Germany in this war and was probably the country most affected by the war. Because most of the war took place in Russia.

In May 1945, Germany conceded defeat in Europe by signing an unconditional surrender in World War II. This document stopped the war on the continent. But in Asia the war with Japan lasted until August of the same year.

The absolute surrender agreement was signed near Berlin on 8 May. The Germans stopped all their operations at 23:01 local time. It was past midnight in Russia.

For this reason, Victory Day is celebrated on May 8 in many European countries and the USA, and on May 9 in Russia, Serbia and Belarus.

Victory Day signified a long and bloody war. Many families in the Soviet Union lost relatives. But Victory Day soon transcended its purpose of commemoration and turned into an ideological tool for the state.

Until nearly 20 years after the end of the war, May 9 was not a national holiday in the Soviet Union and was celebrated only in major cities with fireworks and local events.

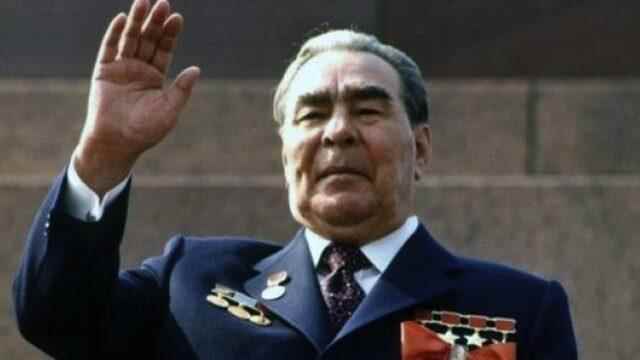

In 1963, then Soviet leader Leonid Brezhnev began to implement a victory cult policy against Nazi Germany. According to some, the purpose of this was to strengthen the country’s weakening ideological foundations and patriotism.

On May 9, celebrations began across the country and military parades began on Red Square. May 9 has been declared a public holiday.

At the beginning of the 21st century, Russian leader Vladimir Putin attached more importance to Victory Day and tried to make it an integral part of Russian identity.

The Victory Day celebrations grew in size, but with each passing year the number of veterans and eyewitnesses still alive and able to attend the celebrations dwindled.

The official discourse on Russia’s key role in defeating Nazism was passed into the constitution as part of a series of amendments in 2020.

With these changes emphasizing conservative values and nationalism, Russian citizens were barred from questioning the historical official discourse on victory.

“The cult of victory was revived in the 2000s with greater fervor than it was during the Soviet era,” says Oleg Budnitski, director of the international center for the history and sociology of World War II at the Moscow Higher School of Economics. That’s why the mood of victory continues to dominate both the media and mass consciousness.

Referring to the ceremonial slogan “We can do it again” in the last 10 years, implying that Russia can take half of Europe, just like in 1945, Budnitski says:

“The cult of victory in Russia was revived in the 2000s with greater enthusiasm than in the Soviet era. This had positive results: the focus was on studies of the history of the war, for example. Millions of documents were made public and digitized. But on the other hand, we began to see an increase in the militarization of the masses.”

Greater truths were ignored in patriotic celebrations. Historians point out that in the discourse of the Second World War or the Great Patriotic War as it is widely used in Russia, the Russians put such basic elements as the huge human casualties in order to stop the German invasion into the background.

The vast majority of respondents said they knew little about where and how their relatives went through the war, according to a 2020 government poll.

According to the survey, only less than a third of 18-24 year olds know when the Great Patriotic War began. (When Nazi Germany attacked the Soviet Union in June 1941)

With tensions in eastern Ukraine after 2014, state media began to put more emphasis on the war with the Nazis.

Russian officials said that the far right came to power in Ukraine during the occupation of Ukraine and drew attention to the historical role of the Russians in defeating Fascism.

The state embraced the commemoration initiatives made by civil organizations for those who lost their lives in the war.

For example, in Tomsk, Siberia, a group of independent journalists launched an initiative called “Immortal Regiment” for those who lost their lives in the war.

This initiative was based on the idea that the public would march on Victory Day with photographs of those who died in the war. This venture quickly turned into a national phenomenon.

In 2015, a state structure with the same name was created. The original founders of the movement were excluded.

The “Immortal Regiment” turned into a government initiative. It has become an event in which public servants, students, and the state media are sometimes compulsorily attended. In this way, the Russian authorities were giving the message that the right thing to do was to hold the celebrations under the supervision of the state.

In 2020, celebrations of the 75th anniversary of the victory in WWII were shifted from May to the end of June due to the Covid-19 pandemic. A magnificent ceremony was held.

More than 20 thousand soldiers, hundreds of aircraft and armored vehicles took part in the parade. The Russian army made a show of power with the modern weapons in its inventory.

And Russia put these weapons into use in Ukraine less than two years later. Russia’s aim, Putin said, was to “demilitarize” and “de-Nazis” Ukraine.

Rapid results could not be achieved in the occupation, such as the capture of Kiev and the overthrow of the Ukrainian Government. But Russian commanders are thought to have pushed for the anniversary of Victory Day, May 9th. If significant successes can be achieved by this date, Moscow will have a chance to rediscover the Victory Day celebrations for propaganda.