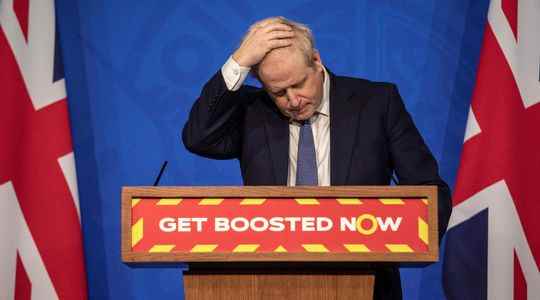

“He will not resign because this man is shameless.” Facing Boris Johnson in the House of Commons on January 31, Labor leader Keir Starmer does not even mention the British Prime Minister’s name. His words echo in an unusual silence. He continues: “The Conservatives are going to have to ask themselves a question: are they ready to risk their reputation and that of the country on the stake of his vanities or are they going to spare us this Prime Minister unworthy of the responsibilities conferred on him? it is their duty. They are indeed the only ones who can stop this farce which has gone on for too long. They will be judged by this decision.”

Case of conscience

What are the Conservatives going to do? “That’s the only question worth asking,” said political scientist Nick Cohen, who “not all Tories are sociopaths and sycophants. Some of them have strong moral principles.” And to add: “All power corrupts, but Johnson’s power corrupts all who defend it.”

A huge case of conscience seems to have gripped the 359 Conservative MPs. In a country where there is no separation between church and state, where Elizabeth II is also head of the Anglican Church and where public schools impose prayer on pupils, morality in politics often arises in the public arena. It is even commented on and argued daily by religious leaders of various persuasions in Thought of the day, chronicle of Today program, the BBC’s flagship morning show between 6 a.m. and 9 a.m. Anglican priests Giles Fraser, Richard Coles and Kate Bottley, to name a few, are stars of radio and television, columnists in the national press and as caustic as they are witty swordsmen on Twitter, where they have a following of almost a million followers.

The “good guy” theory

The Conservatives’ case of conscience actually reveals the end of a system that relied on righteousness and integrity at the top of the state. Because in the absence of a Constitution and written rules, characteristics of the British parliamentary monarchy, political life was based on a moral contract based on what is called across the Channel the “Good Chap Theory of Government”, in other words ” good guy theory”, in short, uprightness and probity as principles of government.

Until recently, the British could indeed count on their elected officials to withdraw from public life in the event of conflicts of interest, sexual or financial scandals, non-compliance with the rules, and of course lying in Parliament, considered a real crime against the parliamentary code of honor. The whole of British public life was thus based on respect for these invisible lines and safeguards. Brexit and Boris Johnson, however, have shaken up the situation and traditions. “There is nothing in Boris Johnson’s public and professional life to suggest that he will ever feel the weight of his conscience,” a recent editorial in The Economist. In other words, what to do when “the guy” who governs does not want to play the game and prefers cynicism to integrity? For many British observers, the PartyGate scandal demonstrates that “the mold is broken” and that the British democratic system is in danger.

In other countries, large-scale demonstrations or a constitutional mechanism would defeat the political fate of a prime minister under criminal investigation. In Britain, only righteousness can lead Boris Johnson to resign and if he refuses to decide for himself, it is up to his party to decide his fate.

An “acid that corrodes the party”

This mechanism is in the process of being put in place. According to the statutes of the Tory party, at least 15% of Conservative MPs (54 today) must send a so-called letter of no confidence to trigger a motion of no confidence in Parliament. These letters have been arriving in dribs and drabs for several weeks, but they are coming. Some MPs announced it in public, sometimes on their Twitter account, such as former defense minister Tobias Ellwood, whose name is circulating as a possible successor to Johnson. Others prefer to remain discreet. The path of defiance was paved by a few party heavyweights who withdrew their support from the Prime Minister and called on him to resign. Like Andrew Mitchell, David Cameron’s former Minister for International Development, Conservative MP since 1987, for whom “the erosion of public trust in our party and our Prime Minister constitutes a national crisis. Nothing like this would have happened under Margaret Thatcher or under Theresa May. These scandals are acid that corrodes the party.”

For Nick Cohen, Boris Johnson is no longer really the subject: “There is nothing more to know or say about such an egomaniac who will not change.” Much more than Boris Johnson, it is in fact the first political party in the country, in power for twelve years, which is currently playing its image and its political survival. “Are the Tories going to fight or let their leader take them down?”