In Kherson, the inhabitants, enthusiastic and relieved, welcomed the Ukrainian army in the same way as they had received the Russian army: with blue and yellow flags on their backs. Leaning against the western bank of the Dnieper, this southern Ukrainian city of 270,000 inhabitants had been the only regional center conquered by the Russians, from March 1st. His release on November 11, after the announcement of the withdrawal of troops by the Russian general staff, constitutes a huge defeat for Vladimir Putin and the epilogue of eight months of occupation. Through the stories of several residents, interviewed by L’Express, months of terror are emerging, but also a number of acts of resistance and solidarity.

Awakened by the explosions on February 24, the journalist Konstantin Ryzhenko – specializing in investigations exposing local corruption – rushes to the town hall of Kherson and finds the haggard mayor there, and civil servants about to leave. Later in the afternoon, the police and the army are nowhere to be found. “I was reading reports that Kherson was falling unresisted, so I got in my car and drove around town with the national anthem on full blast,” the 28-year-old said. hood on the head. “I was very afraid that the Ukrainian army would not come to free us, thinking that we wanted to live with the Russians.”

At the end of the city, the battle for the Antonivka bridge, which spans the Dnieper, is raging. For the columns of Russian equipment rolling in from the Crimea, this is the only way to reach the city. On February 28, the Russian army crossed it and began to square Kherson. “We didn’t even have time to understand what was going on as the city was occupied,” recalls Semen Khramtsov, an employee of the Kherson Museum of Modern Art, who joined the first demonstration on March 5 against the ‘occupation. In Freedom Square, thousands of residents wearing the colors of Ukraine defy the tanks and shout at the Russian soldiers to go home.

When resistance was organized

“The Russians did not anticipate that there would be such protests,” Konstantin said. From mid-March, the National Guard and the Russian riot police violently repressed increasingly small demonstrations (the last ones took place at the beginning of May) and multiplied the arrests. At the same time, the Russians are going door to door to flush out veterans of the Donbass war and the organizers of the demonstrations. “They were putting up posters for May 9 [NDLR : le jour de la commémoration de la fin de la Seconde Guerre mondiale]deployed Russian flags…: the atmosphere was heavy, especially since we had just learned of the Boutcha massacres…”, says Semen, lumberjack beard and tattoos all over his body, who fled to western Ukraine in June.

For his part, Konstantin Ryzhenko, forced to hide to escape the Russian secret services, organizes the resistance. His Telegram channel being a mine of information, the journalist was very quickly contacted by Ukrainian military intelligence. To make sure of their identity, he asks to speak to Vitaliy Kim, the head of the regional military administration of Mykolaiv, or to Oleksandr Sienkiewicz, the mayor of Mykolaiv. Two days later, the latter recruits him by video link. Konstantin sets up a network of informants, trains them in webinars on Zoom. The goal ? “Transmit all the information about the Russians: where they are, where their equipment is, where they sleep, where they eat, how they move, then draw up maps with the movements of the troops, the locations of the weapons.” Thanks to his computer skills, communications are secure. Some members of his network are also responsible for monitoring Ukrainian officials who collaborate with the Russians, others carry out sabotage operations. Konstantin will say no more, but several attacks and attempted assassinations of “collaborators” have taken place in Kherson. Pro-Ukrainian graffiti cover the walls.

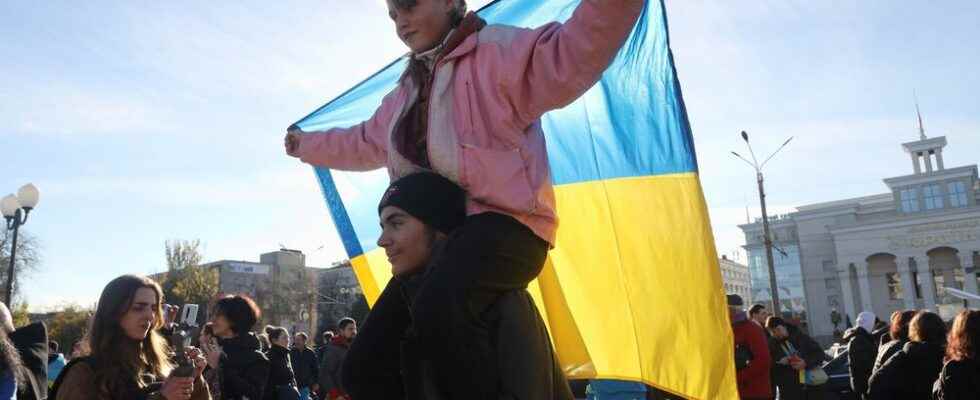

Residents of Kherson, southern Ukraine, celebrate their liberation from Russian occupation on November 14, 2022.

afp.com/Oleksandr GIMANOV

Under the occupation, most of daily life is reduced to the search for food. The Russians have opened their own shops where the products imported from Crimea are very expensive. Medicines, in particular to treat chronic diseases and cancers, are also sorely lacking, and some are taking a lot of risks to bring them into Kherson.

Fortunately, volunteers provide food aid to the most vulnerable. Since August, Daniil Tcherkasskiy, a Ukrainian living in the United States and founder of the organization Ukraine TrustChain, sends between 1,500 and 2,000 dollars a week to four humanitarian groups operating in Kherson, which helps meet the needs of dozens of families. But the activity is complicated by the multiplication of controls. One of the volunteers even disappears for two weeks before being released. “They kidnapped her while she was doing purely humanitarian work, Daniil is indignant.

Occupation Hell

Deprived of everything and terrified, many inhabitants manage to leave the city. In August, only 100,000 people still lived in the city, according to the town hall. Slava Mashnizkiy refused to leave and abandon the Museum of Modern Art that he ran, even when the fighting was close, to monitor and defend it. “We deleted the online museum site so as not to attract attention, confides his friend and colleague Semen. We were lucky: the Russians took all the statues in the city, robbed all the museums except the our.” The museum is still there, but unfortunately not its director. On October 20, Slava’s wife reported him missing. At the beginning of the occupation, the Russians had come to offer him to direct the cultural affairs of the region, but he had refused.

In September, faced with the Ukrainian counter-offensive, the Kremlin tried to further strengthen its hold on Kherson by annexing the region in a sham referendum, under threat of arms. On October 13, Russia orders an evacuation of the civilian population on the other bank of the Dnieper. In their retirement, the Russians took everything, testify the inhabitants: furniture, household appliances, works of art… and even raccoons and llamas from the zoo. They have now settled on the other side of the Dnieper and are digging trenches from which they could easily shell the city. A scenario that worries the authorities as well as the inhabitants. Semen prefers to wait a little longer before “coming home”. But the liberation constitutes an immense relief for the inhabitants, hostages under their own roofs. “My parents called me, it’s the first time they’ve gone out for a walk without being afraid,” he says.

With the liberation of the city, the testimonies of torture, kidnappings or imprisonment multiplied. Researchers at Yale University have already counted some 226 cases of arbitrary detentions or disappearances in the Kherson region between March and October. In at least a quarter of the cases, people were tortured, sometimes electrocuted or beaten with metal pipes. Nearly 400 war crimes have so far been identified by Ukrainian investigators in Kherson and other villages liberated in November, according to President Volodymyr Zelensky. For his part, Dmytro Loubynets, in charge of human rights in Parliament, declared that he had never before seen torture “on such a scale”. With the release, Semen hopes to track down his missing friend.