On February 23, 1942, in Petrópolis, Brazil, two days after sending his publishers the manuscript of the Chess playerStefan Zweig poisons himself with a barbiturate near Lotte, his second wife. On July 2, 1961, early in the morning, in his chalet in Idaho, Ernest Hemingway shoots himself in the head with his double-barreled hunting rifle. Between these two tragedies, on August 27, 1950, in a hotel in Turin, Cesare Pavese kills himself by swallowing a lethal dose of sleeping pills. He leaves a note saying: “I forgive everyone and I ask forgiveness from everyone. Are you okay? No more chatter.”

A few decades after these brief farewells, three French writers take it upon themselves to tell the story of the end of these legends of 20th century literature. Writing is not a party. Driven by “the need to go and wake up old fossils”, Pierre Adrian made himself known with The Pasolini Trailwhere he followed in the footsteps of the master thinker of his twenties. Now in his thirties, he is investigating Pavese. Hotel Roma is a never hagiographic eulogy to the “dark, hard, laconic, sententious Piedmontese”, in whom he found a “lucid companion”. “The love of women will have been Pavese’s great tragedy”, notes Adrian, who sees in it one of the keys to his darkness. He was said to be impotent, but in any case he never managed to build a peaceful relationship with anyone. His notebooks, his diary and his collections served to mop up the melancholy of this great silent man who wrote as if to console himself: “I fulfilled my public role – I did what I could. I worked, I gave poetry to men, I shared the sorrows of many.”

In the same way that Adrian crisscrosses Turin in Hotel Romastaging himself working on his book, Sébastien Lapaque explores Brazil in Checkmate in Paradise. A historical fact bothers him: what could Georges Bernanos and Stefan Zweig have told each other when the former received the latter in January 1942 at his farm in Croix-des-Ames, in Barbacena? We only know that their conversation took place in French – everything else had to be invented. Between the different acts of this imaginary dialogue that resembles a play, Lapaque digresses (with astonishing erudition) on the political situation in Brazil in the 1940s as well as on the life and work of his two duelists. If Lapaque appreciates alcohol (as evidenced by his recent We will have drunk everything), it is above all the wine of the mass which flows in his veins: his books are always irrigated by a mystical dimension. Checkmate in Paradise is a kind of sermon on Corcovado, where Father Sebastian would make himself the mouthpiece of Christ the Redeemer by opposing the “humanist, skeptical Jew” weighed down by despair and the “wandering Catholic” champion of hope (this “despair overcome”). On page 123, the author leaves us with this sentence to meditate on: “In writing this book, I understood that suicide was an intimate defeat from which external causes should not be excluded: public failure, betrayal, distance from one’s homeland, social emptiness.”

A taste for colossi with feet of clay

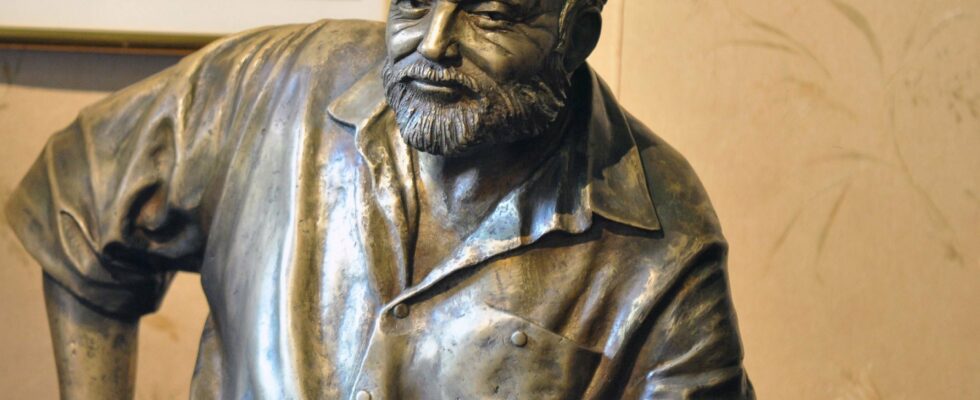

How can we explain that the robust Hemingway also ended his life? This is the subject ofHe only dreamed of landscapes and lions by the sea.where Gérard de Cortanze reconstructs month by month the last year of the author of For Whom the Bell Tolls. In the summer of 1960, the (not so) old man is bitter. A priori, this ogre who drank more than Lapaque had nothing to do with a Kafkaesque ghost like Pavese. Now he too is undermined by impotence. He has trouble writing and goes around in circles in Cuba, watched by the FBI. He goes to get some fresh air in Spain, but must immediately return to the United States for treatment, more precisely at the Mayo Clinic in Minnesota, where he is subjected to electroshocks that aggravate his acute paranoia.

The year 1961 was a descent into hell for him, until his fatal act, which placed him in a dire legacy (his father had already committed suicide, with a revolver). Three years later The King Who Wanted to See the Seahis beautiful book on Louis XVI, Cortanze confirms his taste for colossi with feet of clay. The Hemingway he describes is fragile and human. As with Lapaque with Zweig and Bernanos, we sense a long companionship between Cortanze and Hemingway. At a time when personal development is a hit in bookstores, it is better to turn to these tormented souls to try to understand something about the delicate business of living.

Hotel Romaby Pierre Adrian. Gallimard, 192 p., €19.50.

Checkmate in Paradiseby Sébastien Lapaque. Actes Sud, 336 p., €22.50.

He only dreamed of landscapes and lions by the sea.by Gérard de Cortanze. Albin Michel, 320 p., €22.90.

.