Selecting securities, buying them, strengthening your position, collecting capital gains or losses: the life of a stock market investor is punctuated by decisions… not always rational. Many biases – cognitive, emotional and social – pollute one’s choices. “Everyone is concerned, it’s human,” warns Maxime Viémont, specialist in behavioral finance at Portzamparc.

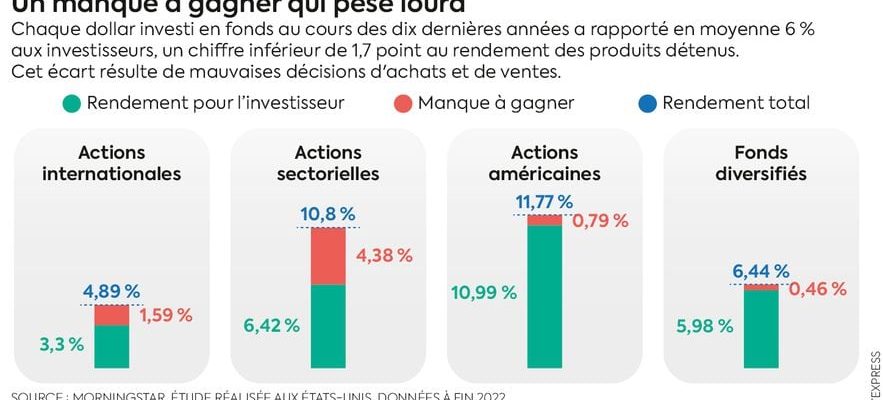

However, the mechanisms are not the same from one individual to another. “Everyone reacts differently depending on their culture, their religion, their gender, but also their past experience,” relates Edouard Camblain, co-founder of the French Institute of Behavioral Finance and Economics. However, these biases have an impact on investment performance. “Academic research has shown that they cause a shortfall of 3.5% per year. When you accumulate this over twenty years, it is considerable,” underlines Maxime Viémont.

Behavioral finance lists more than 200 biases, but some are more significant than others, like the representativeness bias, which leads to extrapolating past trends and thinking that a rising market will continue to rise. In the same vein, confirmation bias hinders the proper processing of information. “It’s the tendency to look for elements that go in our direction or to interpret favorably the information that comes to us,” explains Mickaël Mangot, economist and specialist in behavioral finance.

© / The Express

Don’t neglect biases linked to self-perception, such as overconfidence, which leads you to believe that you know better than others, without anything justifying it. “It encourages you to rotate your portfolio excessively, without diversifying it sufficiently, but it is one of the rare biases which can also have positive consequences, points out Mickaël Mangot. Indeed, it allows you to overcome deeply rooted psychological reluctance and to take certain risks on the stock market, which pays off in the long term.”

Beware of anchoring bias

Conversely, the perception of capital losses is often a source of bad decisions. Loss aversion – which consists of suffering more from losses than taking pleasure in gains – encourages people to stay on secure assets. The status quo bias, to keep investments that have cost in analysis time or money. “On the stock market, shareholders hold their losing positions much longer than their winning positions,” underlines Mickaël Mangot. Not to mention the anchoring bias, which leads to referring to irrelevant values. “This is a frequent phenomenon in personal finances, notes Edouard Camblain. I bought a security worth 20 euros and I recorded an unrealized loss of 10 euros but I am not selling it because I want to see my 20 again. euros, which act as an anchor.” Finally, distrust in the selection of securities: investors favor values that they know well or for which they have a particular affection, to the detriment of good management and diversification rules.

Becoming aware of these phenomena is a first step, but unfortunately it is not sufficient. The important thing is to then adopt a long-term objective. “By setting a course, we are less focused on day-to-day performance, which leads to making mistakes,” indicates Edouard Camblain. At Portzamparc, advisors seek to eliminate their clients’ anchoring biases by removing, in particular, price objectives. In the portfolio statements, the purchase value has also been removed. “We have removed this reference to the past because it should not interfere in decision-making,” explains Maxime Viémont. “The choice to sell must be made solely by referring to the fundamentals of the company and its prospects.” A more radical solution is to limit its interference with the market. “The combination of a planned investment and a very diversified index fund is a much simpler path to wealth than self-control,” laughs Mickaël Mangot.

.