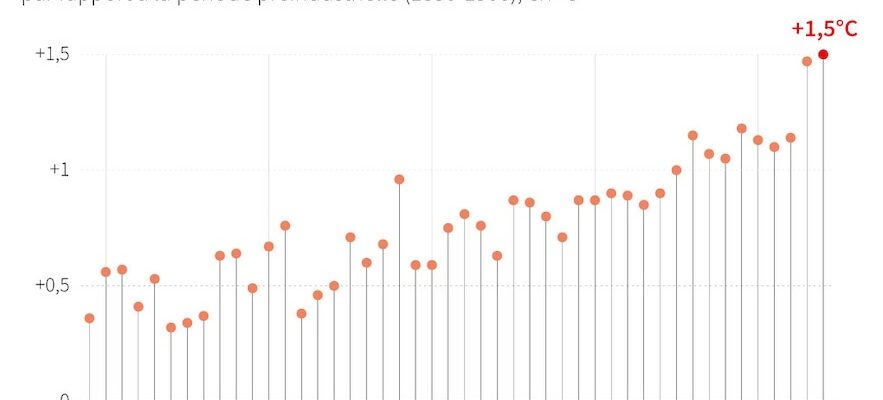

The summer of 2024 was the hottest ever recorded on the planet, where temperature records have been continuing unabated for over a year, with its procession of heatwaves, droughts and deadly floods fueled by relentless global warming.

From June to August, the three months of the northern hemisphere summer saw the highest global average temperature ever measured, already breaking the record set in 2023, the European Copernicus Observatory announced on Friday.

“The last three months have seen the planet’s hottest June and August, its hottest day, and its hottest northern hemisphere summer,” Samantha Burgess, deputy head of Copernicus’ Climate Change Service (C3S), warned in her monthly bulletin. “This string of records increases the likelihood that 2024 will be the hottest year on record,” again ahead of 2023, she added.

China at historic levels

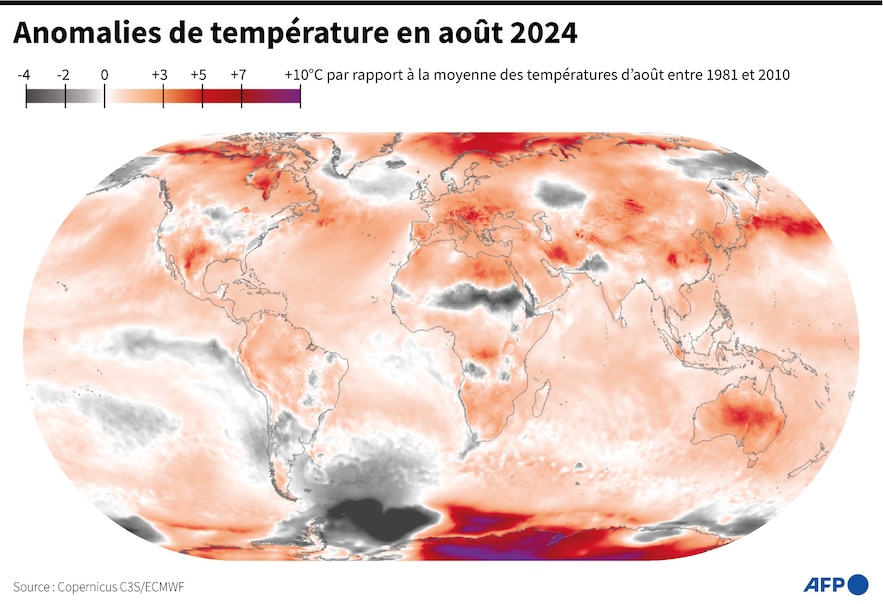

Countries including Spain, Japan, Australia (in winter) and China announced this week that they had measured historic heat levels for the month of August.

“The extreme events seen this summer will only intensify, with devastating consequences for people and the planet, unless we take urgent action to reduce greenhouse gases,” Burgess further warned.

Humanity, which emitted about 57.4 billion tons of CO2 equivalent in 2022 according to the UN, has not yet started to reduce its carbon pollution. But China, the leading polluter ahead of the United States, is approaching its peak emissions, building twice as much capacity in wind and solar as the rest of the world.

Summer 2024 is the hottest on record.

© / AFP

Typhoons, heat waves…

Meanwhile, climate disasters have struck on every continent. At least 1,300 people died in the heatwave during the pilgrimage to Mecca in June. India, regularly experiencing temperatures of over 45°C, tested the limits of its electricity system and saw its economy slow, before an intense monsoon and deadly floods.

In the western United States, fires have raged after several heatwaves that have dried out vegetation since June and caused several deaths. In Nevada, Las Vegas experienced a record high of 48.9°C in July. In Morocco at the end of July, a brutal heatwave caused 21 deaths in 24 hours in the center of the country, which is in the grip of its sixth consecutive year of drought.

Temperature anomalies in August 2024

© / AFP

But full assessments take time: a study published in mid-August revealed an estimate for Europe of 30,000 to 65,000 deaths, mainly among the elderly, due to the heat in 2023.

In Asia, Typhoon Gaemi, which killed dozens of people in July and devastated regions in the Philippines and China, was exacerbated by global warming, a study published in August confirmed. At the same time, Japan was also hit hard by torrential rains from Typhoon Shanshan.

In Niger, a desert Sahelian country made very fragile by climate change, floods in July caused at least 53 deaths and 18,000 homeless people.

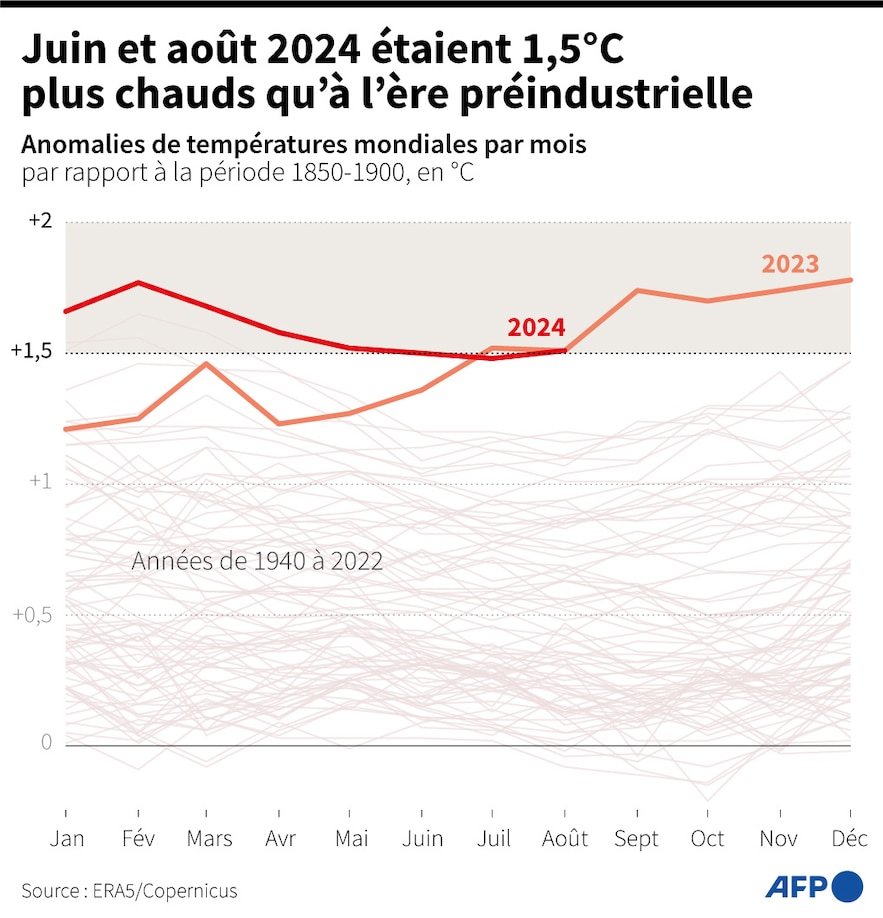

The 1.5°C threshold

August 2024 ended with a global average temperature of 16.82°C according to Copernicus, or 1.51°C warmer than the pre-industrial average climate (1850-1900), in other words above the 1.5°C threshold, the most ambitious objective of the 2015 Paris Agreement.

June and August 2024 were 1.5°C warmer than pre-industrial times

© / AFP

This iconic threshold has already been broken in 13 of the last 14 months, according to Copernicus, for whom the last 12 months have been on average 1.64°C warmer than in the pre-industrial era. After 2023 and its anomaly of 1.48°C according to Copernicus, 2024 therefore has a strong chance of becoming the first calendar year to exceed the fateful threshold.

However, such an anomaly would have to be observed on average over several decades to consider that the climate, currently warmed by around 1.2°C, has stabilised at +1.5°C.

La Niña delayed?

These incessant records are fueled by unprecedented overheating of the oceans (70% of the globe), which have absorbed 90% of the excess heat caused by human activity: the average temperature at the surface of the seas has thus remained at abnormal temperatures since May 2023.

This effect of global warming was accentuated for a year by El Niño and the end of this cyclical phenomenon over the Pacific a few months ago gave hope for a moderation of global temperatures. But in this case, the phenomenon “El Niño was not one of the strongest”, notes Julien Nicolas, a scientist at C3S, for AFP, and La Niña, the reverse cycle synonymous with cooling, is still awaited.

“Some models indicate a continuation of current neutral conditions while others indicate clearly colder than normal temperatures” in the tropical Pacific Ocean, “so it is still difficult to know what the end of the year will bring,” he added.