We can’t say that this is really a surprise. As could be expected, the Marseille Court of Appeal canceled on November 19 the internal regulations of the Corsican Assembly which provided for the possibility for elected officials to express themselves either in Corsican or in French. According to the magistrates, this provision would be incompatible with article 2 of the Constitutionwhich states: “The language of the Republic is French”. A stop all the more predictable as the translation into French was not systematically planned.

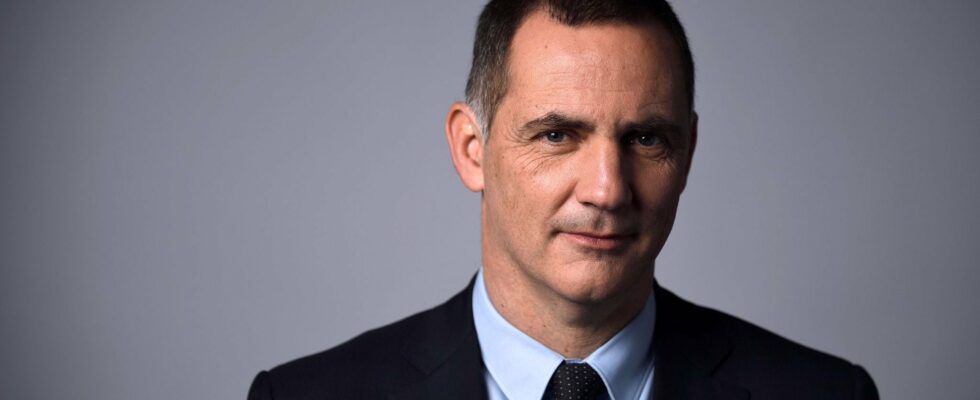

Already on March 9, 2023, the Bastia administrative court made the same decision. Gilles Simeoni, the autonomist president of the island’s executive council, immediately appealed. In the same way, he announced today that he will appeal to the Council of State, and that he also intends to challenge this decision before the European and international courts.

We can criticize many things about this former lawyer who became the political strongman of Corsica, but he knows the law perfectly. He knew very well that his chances of winning before the Marseille Court of Appeal were zero. He is perfectly aware today that he will lose again before the Council of State. If he nevertheless embarks on these procedures, it is because he has another objective in mind, which is this.

For years, Gilles Simeoni has been calling for measures for the Corsican language. For years, the Corsicans have approved this claim by granting it increasingly large majorities. For years, almost nothing has happened. At issue: the interpretation by the Constitutional Council of this famous article 2 of the Constitution. According to this institution, the latter would prohibit any significant measure in favor of so-called regional languages. It is an understatement to say that this version is criticized by many specialists, who point out that it was voted in 1992 with a single aim, to oppose English, with, moreover, the solemn commitment of parliamentarians and the government of the time never to be used against the other languages of France. Orientation that the Constitutional Council has systematically ignored for 32 years. The fact remains: as questionable as they may be, its decisions are binding on everyone, and in particular on the administrative courts and the Courts of Appeal.

From then on, there is only one solution, and Gilles Simeoni knows it perfectly: modify the Constitution. This is why he is leading this legal battle. He intends to demonstrate through the absurd that, in the current state of the law, it is impossible to defend minority languages without changing our fundamental law. An ambitious goal, but not necessarily unrealistic. In 2021, the Molac law – the only one ever passed in favor of regional languages under the Fifth Republic – brought together a large majority of deputies and senators. And a constitutional project for autonomy for Corsica was seriously considered. Hence this formula: “The right to express oneself in the Corsican language within the Corsican Assembly is contrary to the Constitution? Our response: the Constitution must be changed!”

A fight that takes place over the long term

We can approve or not the will of the Corsican nationalist, but not his reasoning because, in this matter, there are only two possible hypotheses. The first? If France, as it asserts, really intends to save its so-called regional languages, the only solution is to grant them co-official status. In short: allow their use – alongside French – in nurseries, public schools, administrations, businesses, public media, political assemblies, etc. Here, this idea is surprising, but it is what is practiced in most Western democracies. In Wales (United Kingdom), the teaching of Welsh is compulsory in almost all schools up to the age of 16. In Alto Adige (Italy), a German-speaking citizen can plead in German. In Quebec (Canada), French is the only official language of business communication. In Helsinki (Finland), the Swedish-speaking minority takes classes in Finnish in the morning, in Swedish in the afternoon. And we could continue by citing Germany, Belgium, Denmark, Spain, Luxembourg, Switzerland and most Western democracies.

Second hypothesis: our country, very late on these issues, continues to refuse to take such measures. And in this case, the rest is known. According to UNESCO, all the languages of France will have disappeared by the end of the century.

It is this alternative that Gilles Simeoni intends to place Emmanuel Macron or, given the current political uncertainty, his successor. It doesn’t matter to him: the fight for minority languages is a long-term one.

.