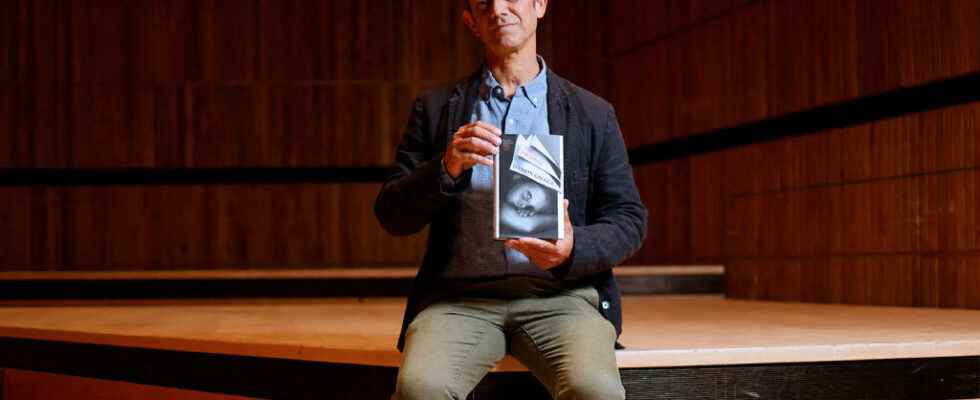

Booker Prize 2021 for his latest novel, South African Damon Galgut delivers with The promise a family saga that deals with the decline of white South Africa.

The latest novel by Damon Galgut, a grand cru, was crowned with the Booker Prize 2021 and translated into French by L’Olivier. This sensitive author with a sharp eye has matured. It is now reminiscent of two of its elders, JM Coetzee and Charles Boschan. From the first, it borrows the meaning of the parable: the whole story of the novel tells another, larger, hollow one. Here it is about the discomfiture of white South Africa, incapable of questioning itself and sick of its own narrow-mindedness. From Bosman (1905-1951), unknown in the French-speaking world for lack of having been translated, but a great figure in South African literature, he inherited an art of critical observation, with a scalpel, from Afrikaner society.

Ironically, he calls the white family in his fiction “Swart” – “Black” in Afrikaans. The latter, based on a farm on the rural outskirts of Pretoria, began a long disintegration in the last hours of apartheid, when the townships were set ablaze and a state of emergency was declared. The mother dies, and the promise she extracted from her husband – to give a shack at the bottom of the garden to their black housekeeper, Salomé, who raised their three children with her – will remain a dead letter for a very long time.

Generational shift

Only problem: this promise is carried like an oath by Amor, the youngest of the family, 13 years old, who witnessed it and does not budge, even if it means looking disturbed. His stubborn fight, emblematic of a generational shift, will become a fundamental fracture line throughout the time covered by the book, from 1986 to 2018. The issue, very simple, is posed in these terms: for or against giving something right for it to be black people?

The dialogues around this question seem straight out of real life:

“- Prevent him from giving a house to the maid, said Désirée, indignant. She will break everything.

– In my opinion, everything is already broken. but this is not the question “.

Unsurprisingly, the relationship of this white family with black South Africa is limited to domination, both before and after the end of apartheid. None of the Swarts have black friends. The driver, Lexington, does not want to get involved when a priest asks him before the end of apartheid his opinion on his bosses:

“- I don’t think anything of them, sir. I do what I have to, I don’t think.

A false statement, Lexington cannot honestly answer. He senses that the Reverend wants something, and giving him what he wants would risk jeopardizing his position. Satisfying two Whites simultaneously is not always possible. »

Impossibility of any relationship

Only the young girl in the house is disturbed by the proximity of Salome’s son, who is her age. She can only see, years later, the impossibility of any relationship with the man who has become an embittered and scarred man, a convict steeped in anger.

As for Anton, the son of the family, an army deserter traumatized by the wanton murder he committed during a raid on a township, he took refuge like so many others in the years 1980, on the beaches of the Transkei Bantustan. He is the only one of his clan to have come out of the Afrikaner bubble to expose himself to the raw violence of his society.

A journey of no return, which makes him a damaged and maladjusted being within his own family, to which he never stops telling his four truths. He is one of the few to take a lucid look at the world around him: ” A new, democratic government in the Union Buildings. […] He wonders if Mandela is there, at this moment, in his office. From prison to throne, I never thought I would see this in my life. Strange that it seems normal so quickly. Whereas before, my God. »

Interior voids

The book closed, what to think? This family chronicle over a period that spans thirty years, the time of a generation, does not give precise keys, but rather food for thought. The author does not analyze the dynamics at work, such as the lamenting posture of many white South Africans, who constantly complain about insecurity, without admitting that it remains rooted in inequalities from which they benefit. still. He also refrains from any “political correctness”. Until the end, his novel keeps blacks, 80% of the population, at a safe distance. They remain complete strangers in the lives of his characters. This contributes to sharing, between the lines, this experience of physical and mental separation that apartheid will have been.

Rather than analyses, the author delivers snapshots. Photographs of his society, which come out of the pages as if taken at random, in lives that are falling apart. At the turn of a sentence, when the story goes through a chance meeting in a bar, we come across a guy who plans to go to Australia because he ” don’t believe in this damn country anymore “.

Above all, Damon Galgut scrutinizes the inner emptiness of his characters: Anton, a failed writer, drowns in alcohol, while his wife drifts into this new religion that yoga has become. The youngest Amor, she isolates herself in Cape Town, at the other end of the country. No redemption here, or so askew, as everything seems to be going in this curious country, ” mix of optimism and unease “. When the time finally comes to keep the “promise”, it is too late. A conclusion that also applies to the “new” South Africa in general.