Hervé Sanson is a specialist in Maghreb literature. It recounts the conditions of emergence of French-speaking Algerian literature in the 1950s as the country plunged into a brutal war of liberation. Clearing their way between militancy and aesthetic imperative, the first generation of Algerian novelists and poets founded a modern and inventive literature in its form and close in its themes to the miseries and aspirations of their people. Maintenance.

RFI: Algerian literature is one of the most dynamic literatures in the French-speaking world. When do the first great Algerian novels date?

Herve Sanson: At the very beginning of the 1950s, before the outbreak of All Saints’ Day on November 1, 1954, there were already the first great texts of French-speaking Algerian literature which appeared and which dealt with the iniquitous system of colonization, which denounced the injustices caused to this colonial system and the growing awareness among Algerians of the feeling of injustice and therefore of the need to remedy it. And so, this growing national feeling is a prelude, indeed, to later, the various novels which will deal directly with the war of liberation.

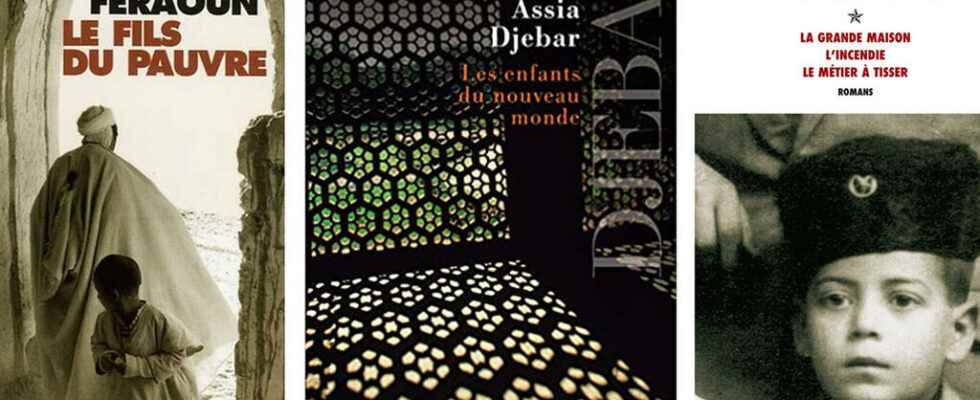

I think of Mohammed Dib with The big house and his “Algeria” trilogy. The Big House appeared in 1952, the fire in 1954, which indeed are a denunciation of the colonial system and all its injustices and of segregation, a form of segregation and in any case the inequalities which reigned between the two communities which then lived in Algeria. And these novels are in fact a prelude to more “committed” novels in quotation marks which will deal with the next stage, namely the war of national liberation.

For example Nedjma, eponymous novel from the pen of a young unknown named Kateb Yacine

The publication of Nedjma is a fundamental date in 1956. Nedjmawhich does not deal, it must be recalled directly, with the war of national liberation since it is the subject of Nedjma, these are the demonstrations of May 8, 1945 and the repression that followed. A certain number of historians today make the Algerian war begin in some way on May 8, 1945, since May 8, 45 represents for the Algerians a founding moment of national awareness and the fact that it did not there is nothing more to expect from the colonial system. Nedjma, that is the theme. Obviously then with this fascinating character, Nedjma, who both like a magnet fascinates, captivates the male protagonists – the four cousins who are the main heroes of this novel – and at the same time who is in a form of escape that we never manages to reach, and which flees perpetually. This character has fascinated generations of Algerian and non-Algerian readers, and this partly explains this magnetism, I would like to say, of this novel which really marked French-speaking Algerian literature.

We must also mention Assia Djebar, one of the few women at the time to take up the pen. She published in 1957, at the age of eighteen, her first novel The Naïve Larks which earned her the comparison to Françoise Sagan. These young authors demonstrate an astonishing great literary maturity. Their novels are not vulgar pamphlets. What are its main characteristics?

Obviously, what marks these different authors is effectively what I would call a strong poeticity. A work on the language, on the rhythm, on the sentence. It should be remembered that Kateb, like Dib too, first presented themselves as poets. Dib said it all the way. While we first know him as a novelist: I’m basically a poet » and Kateb Yacine was also a poet and therefore this poeticity of the language is one of the major criteria of this literature and then also the fact, I believe that the reader perceives it…

Aragon said it when he prefaced Dib’s first collection of poems, guardian shadowshe writes : ” This man writes in my language, it’s strange, I understand all the words and at the same time, it’s not French from France. I sense a strangeness in what is written. I smell a foreign accent. » And indeed, under the French of writing, short in hollow, – I want to say, – either the Arabic mother tongue or the Kabyle mother tongue. And I believe that indeed this strangeness of accent is also one of the essential parameters of this French-speaking literature.

You will agree, this Algerian Francophonie is not self-evident. Isn’t it paradoxical to want to fight colonialism in the colonist’s language?

The paradox, in fact, is only apparent. Why write in the language of the colonizer to effectively denounce the colonial system. Many reasons. First, it should be remembered that these authors were educated in French. They went to French school and in the end, if they hadn’t written in French, they wouldn’t have written. Many of this generation have said it: the language they mastered the most was French. So the question doesn’t even arise when we tirelessly ask those writers who end up getting a little bored: ” But why do you write in French ? » « I can only write in French and I remind you that there was a phenomenon called the occupation, the French colonization of Algeria for 132 years. This explains why I write in French. But apart from that, Kateb Yacine’s formula has been cited a lot, perhaps too much, but a powerful formula. ” French is our spoils of war “. Indeed, the Algerians lived, suffered French colonization for 132 years and at the time of independence, this culture for at least a large part of them they had ingested it. They had assimilated it and in the name of what should they have gotten rid of it, sacrificed it because they were gaining independence? This French language and culture were also an access to modernity, a language of great culture and all the same an access to modernity which the Algerians would have been wrong to deprive themselves of. In any case, that’s how a large number of Algerian writers have felt things and authors like Mouloud Mammeri or Dib have never had a problem, a dilemma to write in French.

If only three novels on the Algerian war were to be selected, what will be your selection, Hervé Sanson?

I obviously quote Mohammed Dib, once again, who is the first with An African Summer in 1959, while the war was not over, to directly evoke this fight for independence. I am obviously thinking, I quoted him, of Mouloud Mammeri with Opium and the Stick (1965). We are in this complexity, precisely of the engagement of the fight for independence. But I still want to add a third author because you still have to quote an author, and not stay in an exclusively male circle. I want to quote Assia Djebar with The Unburied Womanwhich is much more recent, dating from 2002, in which she returns to the role of mujahideenof these fighters of the war of liberation who were relegated after 1962 to the private, domestic sphere and who were somehow dispossessed of their participation in this history.

Hervé Sanson is a doctor of letters, associate researcher at ITEM (CNRS), specialist in French-speaking literature from the Maghreb. To read, his recent article on the subject mentioned in this interview: “A dynamic game with loss (Bleu blanc vert by Maïssa Bey and Écorces by Hajar Bali)”, in Mémoires en jeu, special issue 15-16, winter 2021 -2022, led by Catherine Brun, Sébastien Ledoux and Philippe Mesnard, p. 147-151.