On July 1, 1766, in Abbeville, in the Somme, François Lefebvre, knight of La Barre, was beheaded at the age of 20, after being condemned on appeal by the Parliament of Paris. He is accused of having desecrated two crucifixes and of drawing attention to himself by browsing the small Portable philosophical dictionary of Voltaire blacklisted by those in power. Under Louis XV, we did not joke with the notions of blasphemy and sacrilege. Voltaire, who became Lefebvre’s posthumous defender, died before seeing the first removed from the list of crimes in the Penal Code of 1791. The Chevalier de La Barre was the last to be put to death by royal justice for this double charge. ‘charge.

At the National Archives in Paris, the judgment of his conviction is among the hundred unpublished works and documents brought together under the title Sacrilege! which question, until July 1, the links woven over the centuries between the State, religions and the sacred. “A way of giving sacrilege – here, in its generic form – its political dimension,” underlines Jacques de Saint Victor, co-curator of the exhibition and author of Blasphemy. Brief story of an “imaginary crime” (Gallimard).

From heresy (opinion considered erroneous and obstinacy in defending it) to sacrilege (attack on buildings and objects of worship), including lèse-majesté (hurting divine or royal grandeur) and blasphemy (words or acts offensive to God ), the border is sometimes thin. From the trial of Socrates, in 399 BC, for “corruption of youth”, to the “Casse-toi, pov’ idiot!” affair, in 2008, of Nicolas Sarkozy, regimes have changed, laws have in turn been promulgated and repealed; the way in which the State dealt with religious power has evolved.

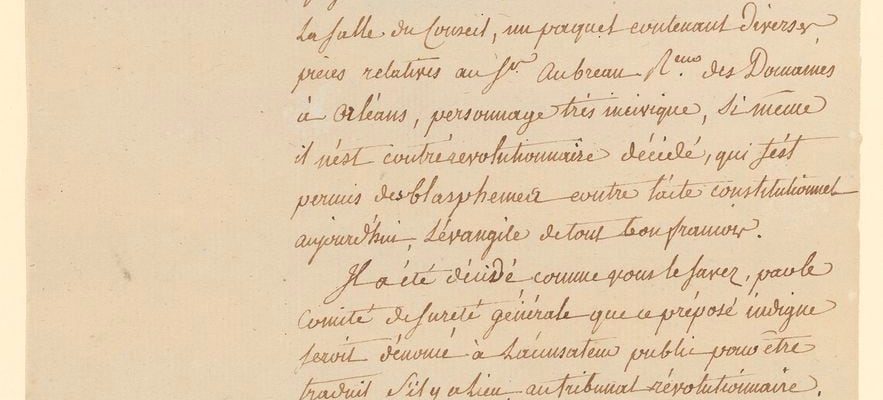

Copy of a letter from the Minister of Public Contributions to the Minister of Justice, July 17, 1793.

/ © National Archives of France

From the 12th century, there was the rise in power then the decline of a “royal religion” shaken by the Protestant Reformation and the related wars. Before the Revolution, sanctifying the State at the same time, eradicated religion and the Republic maintained an ambiguous link with the latter, searching for a substitute for it for a long time, until it came back in force in our contemporary society with the caricatures of Mohammed published in 2005, the Islamist attacks of the 2010s and the assassination of Samuel Paty in October 2020.

Can the State, even secular, do without any form of sacredness, while our recent leaders, from a “normal” Hollande to the Jupiterian Macron, follow one another and are not alike? An edifying illustration of an archaism which persisted in France until… 2013, the offense of insulting the President of the Republic, established in 1881, was contested even before its adoption, leaving, through its vague name, the door open to disproportionate use. However, it was little used, with no head of state using it from 1895 to 1940.

After the repressive parenthesis of the Vichy regime, prosecutions under this charge remained extremely rare, except under de Gaulle, in the context of the OAS attacks. The last took place in 2008 against a Left Party activist who transformed President Sarkozy’s unfortunate response to a man who had refused to shake his hand at the Agricultural Show into a political slogan. This case, which caused a lot of ink to be spilled, led straight to the abolition of the offense five years later, following a ruling by the European Court of Human Rights.

.