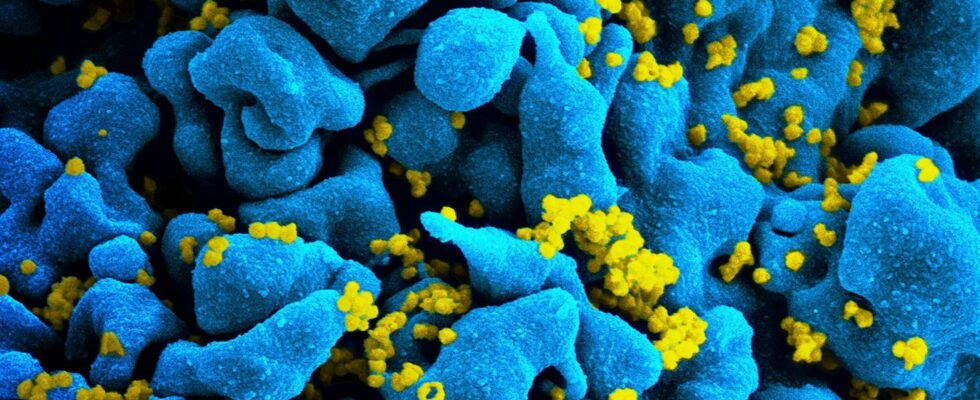

New medical feat. A German man in his sixties has reportedly been cured of HIV, the virus that causes AIDS. Tested HIV-positive in 2009, he stopped taking his antiretrovirals in September 2018, and has not suffered a single relapse since. “The more time that passes without needing HIV therapy, the more confident we are in a complete eradication of HIV,” explained Christian Gaebler, an HIV specialist at the Charité hospital in Berlin, where the patient was treated.

This patient, who wishes to remain anonymous, would thus become the seventh person in the world to have been cured of HIV to date. A feat made possible by a method as astonishing as it is promising, discovered in the 1990s: the mutation of the CCR5 proteins on the third chromosome makes it possible to eradicate the virus from the human body. And for good reason, when the CCR5 proteins malfunction due to this mutation, the HIV strains are unable to attach to CCR5 receptors, and cannot penetrate the individual’s organic system.

CCR5 protein, key to this cure

Thus, like five of the six other people cured of HIV, the German patient received stem cell transplants. But the case of this seventh patient now in remission would have allowed a breakthrough: while until now, research focused on donors with two copies of the defective CCR5 gene, it would seem that a single copy of the gene could be sufficient. In any case, this is what the results of the transplant of the sixty-year-old would have allowed to be demonstrated.

Because his donor had only one copy of the CCR5 gene, meaning his immune cells probably had only half the “normal” amount of the protein. “So the study suggests that we can expand the donor pool for these types of cases,” Dr. Sharon Lewin, director of the Peter Doherty Institute for Infection and Immunity in Melbourne, Australia, said at a news conference last week.

A technique reserved for a small number of patients

However, “we now need to understand how this new immune system was able to graft itself onto the patient and how his body was able to eliminate all the HIV reservoirs over time,” said Dr. Gaebler, who expressed surprise at the positive result. The patient’s initial immune system could have played an important role.

This is why researchers remain cautious and prefer to temper the enthusiasm of the general public. Firstly, the mutation of the CCR5 protein on the third chromosome remains very rare: less than 1% of the world’s population carries it, and its location is concentrated in northern European countries. Secondly, this transplantation can only take place on HIV-positive patients with cancer.

Finally, since the German patient himself only has one copy of the gene, like his donor, these two genetic factors combined may have increased his chances of recovery. “The donor’s innate immune system may have played an important role here,” confirms Christian Gaebler. One thing is certain: this method of transplantation is not likely to be used on a large scale any time soon.