“I was lucky,” she says modestly when asked about her presence wherever politics was established, constructed, accomplished. Michèle Cotta could have said “I worked a lot” but political journalism seems to be such a passion for her that it has never been synonymous with obligation, much less weariness. In the first volume of My Fifth (at Bouquins), a fascinating book, the journalist who studied at L’Express alongside Françoise Giroud and Catherine Nay, recounts her first steps in journalism and the mysteries of power, from the De Gaulle presidency through the election of Pompidou, then that of Giscard until the arrival of Mitterrand at the Elysée in 1981. What character traits seem essential to reach the Elysée? Are we doing politics today like we did yesterday? So many questions that Michèle Cotta was kind enough to answer, with the mischief that characterizes her.

L’EXPRESS: Reading you, we realize that politics is often a matter of minimalism. Events and destinies are sometimes changed with a word. You recount Giscard’s “Yes, but” in 1967…

Michèle Cotta: The “yes, but” addressed by Giscard to General de Gaulle on January 10, 1967 completely corresponded to the character. The legislative campaign was about to begin, Valéry Giscard d’Estaing, deprived of the Ministry of Finance a year earlier, thus indicated to the President of the Republic, with two sharp words, that his support was not unconditional.

I also think of François Mitterrand’s “quiet strength”, imagined by advertising executive Jacques Séguéla. The formula is effective because it immediately softens the image of Mitterrand and reassures public opinion about the man who at that time represents for many the chaos, the end of the Fifth… Another (very small) episode also counts in the destiny of Mitterrand, this time it is not about words but about a very small physical change: he has his incisors filed down and immediately becomes more calming.

And how can we not mention Chirac’s “dry five-year term”, a formula which means nothing except that the president is in favor of the five-year term but without any other institutional change. He does not use it out of conviction, he does not believe that it is a capital modification of the Fifth Republic, but he simply gives in because part of the political world is asking for it and he has not does not want a confrontation with his cohabitation Prime Minister, Lionel Jospin. But it was ultimately a major change in political life.

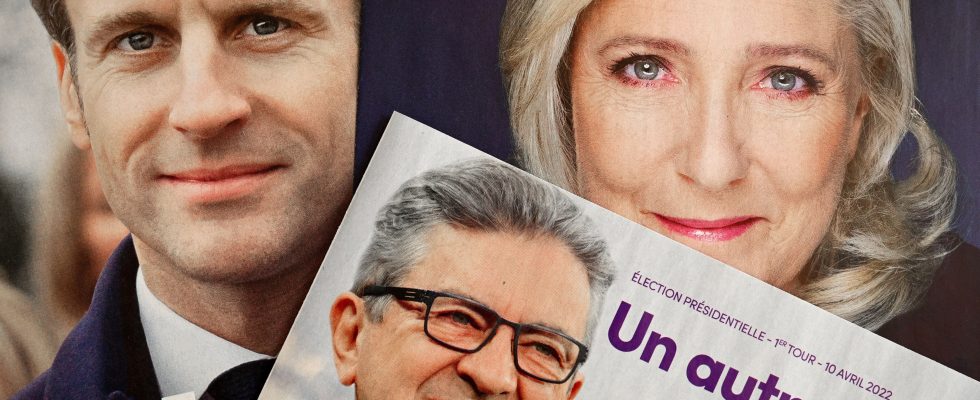

Can the era still be satisfied with this finesse? When we see Mélenchon and his way of doing politics like a bulldozer…

I believe that the times can still allow that. Mélenchon’s great speeches are quite interesting when you read them, they galvanize some and outrage others but they change nothing. It is aimed at a specific population, it does not go beyond it, it speaks to its electorate. There would be a finer way for him to do politics… But clearly, he doesn’t do it. As for the Republicans, they rather choose picrocholine fights…

You describe very well the changes of certain political leaders who, sometimes in a second, transcend themselves and become these candidates that we could not have imagined yesterday.

Considering being elected President of the Republic is not an easy task. It takes, to say the least, immense self-confidence. And a strong shell. When Pompidou makes his first speech to the National Assembly and the opposition vigorously denounces his time with Rothschild, he becomes confused, turns white, almost loses the thread of his speech. But he learns quickly. This will not happen again. From 1965, when General de Gaulle maintained suspense over his candidacy, the barons all gathered around him! They had all been part of the Resistance, they had all accompanied de Gaulle from the start. And yet, in their eyes, the one who had not resisted and had joined the Gaullist adventure much later stood out. Pompidou possessed something quite strong: a real authority, a real charisma. Only illness undoubtedly prevented him from giving his true measure.

François Mitterrand was also driven by incredible self-confidence. As early as 1962, he said to himself that he was going to become President of the Republic sooner or later. What stubbornness…

As for Chirac, I don’t know what he believed in, but he believed that we simply had to be there. He transforms once elected president. It takes on an international dimension that we did not suspect at home. He becomes the one who dares to say no to the Americans when declaring war on Iraq.

François Hollande is the exception. He did not changed. I am convinced that if he had maintained his decision on the loss of nationality for the perpetrators of the attacks, if he had imposed his decision on parliamentarians based on the majority will of the French, he would perhaps have blocked the way to Emmanuel Macron. But he did not dare to face his own majority.

You also describe the incredible role and weight of certain shadow advisors. Could strategists as powerful and secret as Pierre Juillet and Marie-France Garaud still exist today?

After the publication of my book, Edouard Balladur telephoned me to tell me that I had exaggerated the role of Garaud and Juillet. I am not sure. However, I think that such influential advisors can no longer exist today because the memory we have of the two you mention is almost ridiculous, Juillet resigning all the time, Marie-France making dirty tricks…

We will never know if, as Balladur says, Georges Pompidou wanted, at the end of 1973, to keep Marie-France Garaud away. Emmanuel Macron may make his decisions in his office one-on-one with Alexis Kohler, but the latter is an advisor in the spotlight. It was completely abnormal for an advisor like Pierre Juillet to respond to Chirac who thanked him after winning the Paris mayor’s office: “It’s the first time that a horse has thanked its jockey.”

Do you regret the disappearance of the left-right bipolarization?

Yes because things seemed easier: people knew where they lived. Extremists were in the minority, while this “at the same time” spawned radical extremists on both the left and the right.

When Giscard said “We must govern in the center”, he still retained the left and the right. Now, with such a large far right, the central bloc would only make sense if the Republicans joined it. But you have to hear the LRs talking about Edouard Philippe… Even if these are postures, we can clearly see that reconciliation is not for tomorrow.

Our time is asking a lot about “the right distance” between political leaders and journalists. What is your opinion ?

The right distance is the one that allows you to see everyone and balance your sources. I think that deep down it’s a question that I can’t understand… To decipher the political strategies of each side, we have to make them talk. Of course, it’s not a matter of taking what a politician tells you at face value, but if you don’t see him, you don’t know what he thinks.

Have you ever found political matters dry and drying?

Arid certainly not, drying either! I remain convinced that politics dominates everything, decisions are political: economic, societal decisions… Characters pass, and so do generations. The policy remains.

.