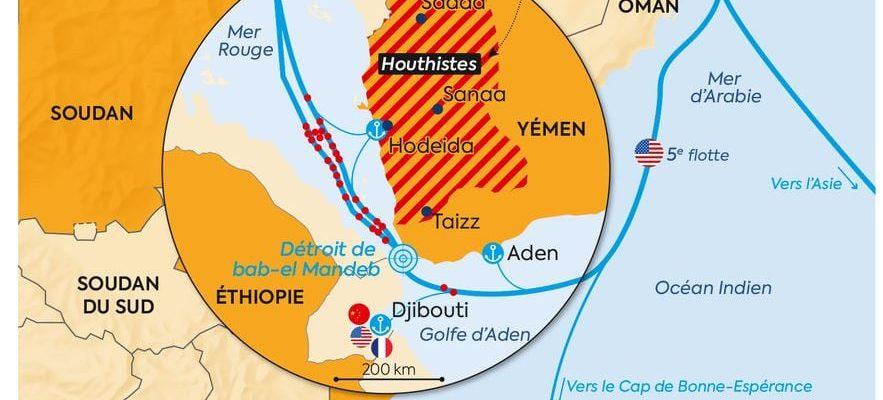

Since mid-October, Yemen’s Houthi rebels have been disrupting navigation in the Red Sea, in the Bab-El-Mandeb Strait, a strategic location through which 40% of container traffic and 12% of global commercial traffic transit. In the name of defending Palestinians in the conflict between Israel and Hamas, this group fires drones and missiles at commercial ships, as well as military vessels that provide maritime security in the area. Since mid-December, the United States has set up a coalition responsible for securing the area. To decipher the consequences of this crisis, L’Express interviewed David Rigoulet-Roze, associate researcher at the Institute of International and Strategic Relations (Iris), editor-in-chief of the journal Strategic directions (L’Harmattan) and co-director of the work The Red Sea: desires and rivalries over a strategic space (L’Harmattan, 2023).

L’Express: After repelling attacks in the Red Sea thanks to its fleet, the United States, at the head of the anti-Houthi coalition, decided since January 11 to directly strike the group in Yemen. Within days, the American and British armed forces bombed around ten military sites of the Houthi rebels located in Yemen. Why did you take this step?

David Rigoulet-Roze: The strikes were more or less expected, but until now there had been a sort of prudential logic on the part of the Americans, in order to avoid a direct confrontation, for two reasons: first, in relation to the problematic in international law, to the extent that it is appropriate to have legal coverage for operations of this type; then, in relation to the risk of escalation and potential spiraling. They considered that it had become necessary to restore a certain deterrence. They estimated that the red line had been crossed on January 9 with the launch of a wave of 21 shots (18 drones and 3 missiles, including anti-ship missiles) targeting not only commercial ships but also military buildings. present to protect maritime traffic, a fortiori since the establishment of the international naval coalition of around ten countries established on December 18 by the United States. In addition, a UN Security Council resolution, Resolution 2722, passed on January 10 and ordering the Houthis to cease their destabilizing actions on freedom of navigation and the security of the region, now provided legal cover. Furthermore, the Houthis do not embody Yemen’s governmental legality [NDLR : ils contrôlent depuis 2014 le nord-ouest du pays, dont la capitale, Sanaa, et le port de Hodeïda].

The Red Sea was not a focus before the Houthi attacks began. Had we forgotten how dangerous this terrain was?

Indeed, there has recently been a form of historical “forgetting” of the Red Sea, in favor of the Strait of Hormuz, rightly so in relation to the strategic issues of the Gulf. But we forgot that there was another strait which was also very important, namely the Bab-El-Mandeb, “the gate of lamentations”, which is aptly named in view of what is happening today. Destabilization, in a multiscalar logic, first weighs regionally with significant local impacts, notably for Egypt’s financial revenues conferred by the taxes induced thanks to the Suez Canal (just behind tourist revenues), but, beyond that, potentially on the global economy.

Africa, Red Sea

© / Legends Cartography

Despite the American response, the Houthis do not seem to weaken in their determination, and are even becoming emboldened: on January 14, a cruise missile targeted an American destroyer, theUSS Laboonoperating in the southern Red Sea.

The Houthis can increase their strikes. This is also what was announced by the leader of the Houthis, Abdel Malek al-Houthi, who spoke of “even more important operations”. The increase in Houthi fire leads to insecurity which means that there is a diversion of maritime flows by large shipowners via the Cape of Good Hope, which extends transport time by around ten days and doubles almost its cost, with significant expectations for the global economy in terms of a potential rise in inflation and a lengthening of logistics flow chains, already perceptible in certain automobile manufacturers’ factories, such as Tesla in Germany. Europe is in a very fragile situation in terms of energy independence in particular. We have already seen this with the war in Ukraine. But this could become even more complicated if the situation deteriorates in the Red Sea, through which some 5% of the world’s crude oil, 8% of liquefied gas and 10% of petroleum products transit.

China is very impacted by this crisis due to its goods passing through the area to reach Europe, but it has remained very cautious in its position.

China is very worried by evoking its “concern” and calling on all parties “to exercise restraint”, according to the established expression, even if it does not want to acknowledge it publicly. In fact, even though it is one of the first powers concerned by the security of maritime flows linking Asia to Europe via the Red Sea, it did not see fit to join the naval coalition established in mid-December by the Americans, because it does not want to give the impression of aligning itself with what could appear to be a defense of Western interests and because it intends to spare Iran, with which it maintains relations close relationships.

These latest developments raise fears of an escalation; are we facing a regionalization of the conflict in Gaza?

In the case of the Red Sea, there is both a regionalization and an internationalization of the conflict. A regionalization, because there is an explicit connection with the war in Gaza which is waged by the Houthis, who, by being part of the axis of “moukawama” (the “resistance to Israel”), bringing together the “proxies” Iranians in the region, intend to demonstrate their solidarity with the Palestinian cause in general, and Hamas in particular. Including by hijacking ships, which is nothing less than a form of piracy, as in the case of Galaxy Leader, hijacked on November 19 with its 25 crew to the port of Hodeida. If we were in the presence of a classic State and not a “failed State” like Yemen, this could constitute a casus belli. This is also what makes it possible to graduate the response to avoid going to extremes. But there is also a de facto internationalization due to the mentioned impact on the world economy of this regional conflict configuration, which is not always the case.

The Houthi rebels in Yemen are therefore part of the “axis of resistance” led by Tehran against Israel and the United States. Can the Iranians go further in their support for the Houthis, in particular by launching maritime attacks?

The Iranians do not have a navy capable of directly confronting the US Navy in the Red Sea, but they have the capacity to cause nuisance and disrupt maritime flows and, therefore, indirectly, to have an impact on the Mondial economy. We are in a hybrid war logic. They had a spy ship in the Red Sea, the Saviz, which had been permanently damaged in April 2021 by an unclaimed operation. THE Behshad took over in August 2021, which likely transfers useful intelligence to the Houthis for the identification of ships transiting the Red Sea. This is what the Americans point out when they declare on December 22 that “Iranian support for the Houthis is solid and translates into deliveries of sophisticated military equipment, transmission of intelligence, financial aid and training, [même] if Tehran delegates operational decisions to the Houthis”. The whole difficulty for regular forces lies in managing the hybrid nature of the conflict at work, because there is a risk of escalation, even though we are in a logic of avoiding a direct confrontation. This is the strength of the weak and the weakness of the strong of the actors of hybrid war. But, in the meantime, the capacity to cause harm is proven. Tehran is on the line of peak, which consists of not exceeding red lines in order to avoid uncontrolled skidding and an uncontrollable spiral. This is not yet the case for the moment. But there is a cumulative multiplication of elements which favor this logic of escalation, even if it is not officially desired by any of the actors present.

.