Imagine a field of solar panels, installed on the edge of a forest. A powerhouse of thousands of cells with inclination and exposure adjusted to the millimeter. Over the years, well before the end of their life cycle (around 30 years), several panels malfunction, immediately replaced by others. But the reserve stock is disappearing quickly, too quickly, and it is impossible to renew it since the manufacturer – very often Chinese – has gone out of business. Welcome to the real world of European solar energy producers.

Technology is evolving so much that the models chosen ten years ago, with a precise size, power and connectivity for a power plant, are no longer mass-produced. They would have to be produced to measure. Unthinkable given the cost. “It would be like doing haute couture in a standardized world,” image William Arkwright, managing director of Engie Green, which operates 250 solar power plants in France. Result: a few locations remain empty, so many holes in the constellation of photovoltaic panels. Could the faulty elements not have been immediately sent to the recycling box, but could they have been repaired? This is the improbable blind spot that Solreed wishes to fill.

The start-up wants to “become the first European player to extend the life of solar modules”, says Luc Federzoni, one of the two co-founders. Of course, repairs already exist for individuals, with companies offering to repair roof panels. But this solution does not exist on an industrial scale. Incomprehensible and embarrassing for a sector at the heart of the energy transition. “Sustainability will become a major issue,” confirms François Legalland, director of CEA-Liten, the research institute which hosts Solreed on its campus in Bourget-du-Lac (Savoie).

France could accumulate between 1.5 and 1.8 million tonnes of photovoltaic panel waste by 2050, according to the International Renewable Energy Agency (Irena). A part could be avoided or postponed in time thanks to a real repair strategy. “A small rate of failures in a huge market, that counts,” points out Luc Federzoni. “The breakdowns led to a shortfall of 6 gigawatts in Europe last year, or the production of one and a half nuclear power plants.” Far from being negligible.

The French start-up Solreed offers solar panel repair solutions.

© / BL / L’Express

99% success

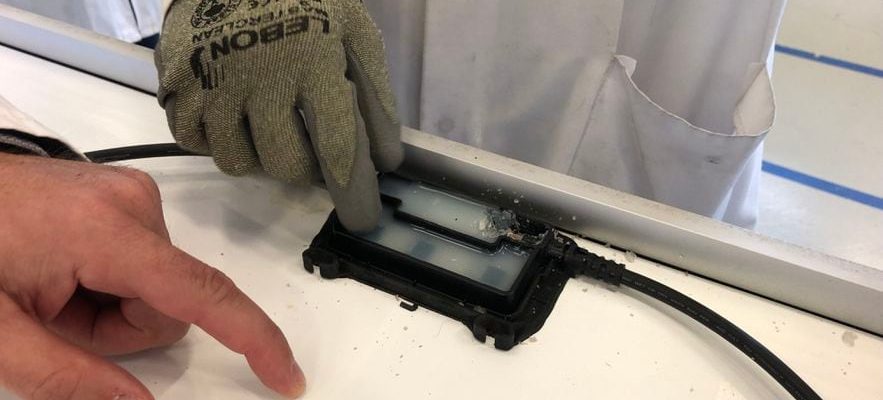

The energy company Engie, which supports the start-up, has done its accounts. Of the 6 million solar panels it has across the country, between 2,000 and 3,000 are replaced each year. In a growing sector exposed to extreme weather events, there is a good chance that this number will increase. This is why the company donated around a hundred faulty cells to Solreed last summer. History of testing the viability of the project. In ten days, it repaired… 99%. “All have regained their initial performance”, while a solar panel loses 0.4% of its efficiency per year, specifies Matthieu Verdon, the other co-founder. Sometimes it only takes a little to bring them back up to standard: change the connectors, retype the rear layer or replace a diode.

In the rectangular laboratory at Bourget-du-Lac, a CEA employee is testing different manipulations – on behalf of Solreed – on a ten-year-old panel producing 260 watts upon purchase. After repair, the machine displays an output of… 262 watts. Like new. “And to think that it was going to the landfill,” says Christophe Thomas, in charge of the Prospecting and development teams at Engie Green. According to estimates by the start-up’s bosses, repairing a solar panel would save 30% compared to purchasing a new one. And, at the same time, acquire valuable knowledge on the different models and their vulnerabilities.

Because precisely locating faults is sometimes difficult. Several options exist. A visual inspection can identify an apparent defect, for example after strong winds or hail. It is also possible to observe, via monitoring stations, a lower efficiency in a sector and to trace it back to the row of solar panels concerned. But the matter becomes difficult to precisely distinguish the defective cell(s), especially in power plants spread over tens of hectares. They can be identified by drones equipped with thermal cameras, except that this type of aerial outing is only carried out once or twice a year. “But by intervening early, we increase the number of repairable panels,” insists Matthieu Verdon. Hence the objective, for Solreed, of developing new continuous monitoring and diagnostic systems to detect signs of weakness. “We could then go and repair as close as possible, on the site, perhaps even without disconnecting the panel in question,” anticipates the co-founder. This type of option is obviously of interest to Engie, but also to other players who are making inquiries. For Solreed, the future looks bright.

.