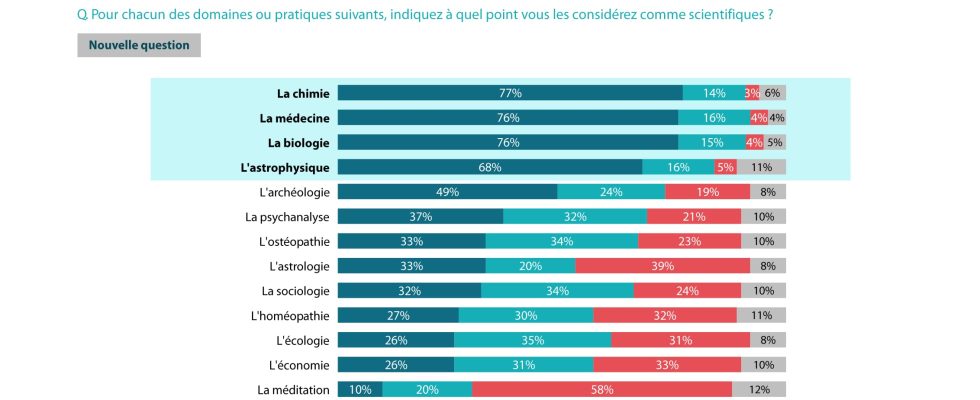

The latest OpinionWay survey for Universcience on critical thinking reveals the confusion that reigns in the minds of many French people about what science is. Over there formulation of one of his questions (“For each of the following fields or practices, indicate to what extent you consider them scientific”, with several propositions such as: chemistry, medicine, psychoanalysis or astrology), this survey supports the idea that we can divide the fields of knowledge into two categories: sciences and the rest. And it induces confusion between sciences – which seek to understand – and practices – which seek to act. Providing no definition or criteria for what science is, it leaves everyone to interpret this word in their own way and according to their own understanding.

These confused notions are quite revealing of what the French school system transmits, namely a categorization between disciplines which are sciences and others which are not. Categorization sometimes refined by a distinction between so-called “hard or exact” sciences and so-called “soft or human” sciences.

I myself have long been subject to this confusion. When I left the Ecole Polytechnique, despite five years of study in mathematics and physics, although they were considered the pinnacle of French scientific education, I still did not know what science was! I only realized it the following year, when I started research in a psychology laboratory. Paradoxically, it was by immersing myself in a discipline usually considered non-scientific that I finally understood what science was. How is it possible ?

Science is not a discipline, but an approach

This is because science is not the prerogative of one or more disciplines. Science is a process, a method for asking questions about the world and obtaining reliable answers. This approach consists of, firstly, formulating hypotheses (for example: overexposure to screens increases the risk of autism). Second, to derive testable predictions from these hypotheses (for example: if this hypothesis is correct, in a cohort representative of the population, children most exposed to screens will also have a greater prevalence of autism than those less exposed) . Third, to carry out observations or experiments allowing these hypotheses to be tested: measuring exposure to screens, diagnosing autism within the cohort and doing statistics to test the link between the two.

Throughout, it is important to keep in mind alternative hypotheses that might predict the same observations. For example, the fact that autistic children are more attracted to screens than othersin a way to look for situations where hypotheses make different predictionsand thus collect data allowing them to be decided between them.

Finally, fourthly, depending on the results observed, we are led to accept, reject or revise the initial hypotheses and then build new hypotheses, predictions and observations. Through this iterative process, our hypotheses make ever better predictions, become ever better supported, and ultimately constitute reliable scientific models and theories.

This approach is the very heart of science, and it can be applied to all aspects of the world about which we ask questions: the functioning of the Universe, the Earth, living beings, but also the human being and human societies. All disciplines that study the real world using this approach can claim to be a science. The distinction between hard and soft sciences is unjustified from this point of view. Moreover, no science can claim to be “exact”, each of which can only provide necessarily imperfect models of reality. Only mathematics can be considered exact, but this is because they are purely intellectual constructions which do not relate to reality. We can therefore consider that they do not constitute a science, even if they are used by all sciences.

Parasite discourses around “science”

What can distinguish disciplines from each other and lead one to think that some are more scientific than others is the fact of being more or less parasitized by discourses relating to their subject, but not relating to the scientific approach. . No discipline escapes it – let’s remember the physical “theories” of the Bogdanoff brothers, but some are more vulnerable to it than others. We can concede that within the human and social sciences, we frequently hear speeches which state their hypotheses as established truths, with little concern for putting them to the test of the facts.

This is what distinguishes psychoanalysis from scientific psychology, and certain currents of sociology or educational sciences from each other. But these are not intrinsic flaws in these disciplines: they are rather intellectual traditions running through each discipline and consisting of considering that speculative discourse can be sufficient to understand certain objects such as humans and society. These traditions are reinforced by the fact that these subjects fuel social debates in the media and elsewhere, where the scientific approach is a secondary concern.

As for practices such as medicine, psychotherapy or teaching, they do not aim to explain but to act. They are not sciences, but they still need sciences: on the one hand, to base their actions on a correct understanding of what they aim to modify and the means to achieve it; on the other hand, to rigorously evaluate whether the proposed practices really have the hoped-for effects. This is how medicine uses scientific knowledge to imagine treatments, and uses the experimental method to sort between those who treat: certain medications, certain physiotherapy or even psychotherapy practices; and those who do not treat: other medications, or even homeopathy, osteopathy, and other psychotherapies, such as psychoanalytic treatment.

To overcome these vain debates and surveys such as: “Is this discipline a science?”, we can only hope that the school system finally manages to transmit to each student, not only basic knowledge about the world from different sciences, but more fundamentally the very meaning of the scientific approach and the main methods it uses.

Franck Ramus is a researcher at the CNRS and the Ecole Normale Supérieure (Paris)