“I was born on the beach, as all the Sète people say”, claimed Valentine Schlegel, who, throughout her life, remained attached to her native port, this end of the Mediterranean, where, at the end of the 19th century, his grandfather had come from Switzerland to set up as a cabinetmaker and furniture dealer, taken over in 1925 by his son Eugène, the very year of the birth of Valentine, the youngest of his daughters. In Sète, canvases by local painters adorned the windows of Schlegel stores at the time, which regularly earned them praise from the local press, just as the cabinetmaking and tapestry work carried out in the workshop attracted the bourgeois houses of the city.

It is undoubtedly here that the little girl awakened her eye for art, before trying her hand at drawing when, as a teenager and member of a Girl Scout group, she illustrated her sea shanties notebooks in a fervent hymn to the big blue. At the Girl Scouts, the young Valentine finds Agnès Varda, whose family fled Brussels during the Occupation to find refuge on these peaceful shores. The Varda family then lived on a boat moored opposite the Schlegel villa. Between the future sculptor and the filmmaker in the making, a long-term friendship begins, punctuated by numerous shots that the second will take of the first, which remain today precious testimonies of Valentine Schlegel’s artistic career.

Valentine Schlegel, “The three bears” vase, ceramic, 1955.

/ © ADAGP, Paris, 2023 / Cnap Photo Fabrice Lindor

In 1942, Eugène requested the admission of his youngest child to the Montpellier School of Fine Arts, where his eldest Andrée had preceded her. Valentine was 17 when she joined the prestigious establishment. She will stay there for three years, and will be noticed there for “certain gifts” and “solid qualities of work”. Even if she is one of the students whose systematic absences during ceramic history are reported. Spicy detail when you know that it is in this discipline that she will soon shine. Very quickly, she moved to Paris, in the studio, rue Vavin, of her fellow student from Montpellier Frédérique Bourguet, with whom she modeled the earth, drawing inspiration from Mediterranean antiquity.

While the revival of the ceramic arts takes place, under the impetus in particular of Picasso, who is interested in the practice, Valentine Schlegel is not long in favoring coil modeling, shaping biomorphic pieces and reinventing with these organic forms, as if emerging directly from the earth, the aesthetics of the vase, without sacrificing its usual function. “The most beautiful pots were painted on the paintings, by Braque for example, with a new freedom, to have a life of its own, a pot must also be a sculpture”, she said.

The young ceramist deepens this work alongside Andrée, married to Jean Vilar who has just created, with the help of the emblematic couple of art dealers Zervos, the Festival d’Avignon, an adventure in which Valentine takes part every summer, alternately taking on the roles of props designer, decorator, costume designer or stage manager. This is the beginning of a prolific career, which will find its apogee shortly after in ceramics and then sculpture, as the Fabre museum in Montpellier traces it to us in the salons of the Hôtel de Cabrières-Sabatier d’Espeyran. Orchestrated by Michel Hilaire, the institution’s director, with the scientific collaboration of the curator Florence Hudowicz, the exhibition presents a selection of remarkable objects, ceramics and models, as well as photographs taken by Agnès Varda then, later, by Suzanne Fournier, the artist’s other sister. “We want to testify to the diversity of the production of Valentine Schlegel, ceramist then sculptor, who combined her talents and her taste for freedom for the benefit of a true art of living, but also to evoke her poetic relationship on a daily basis”, underline the commissioners.

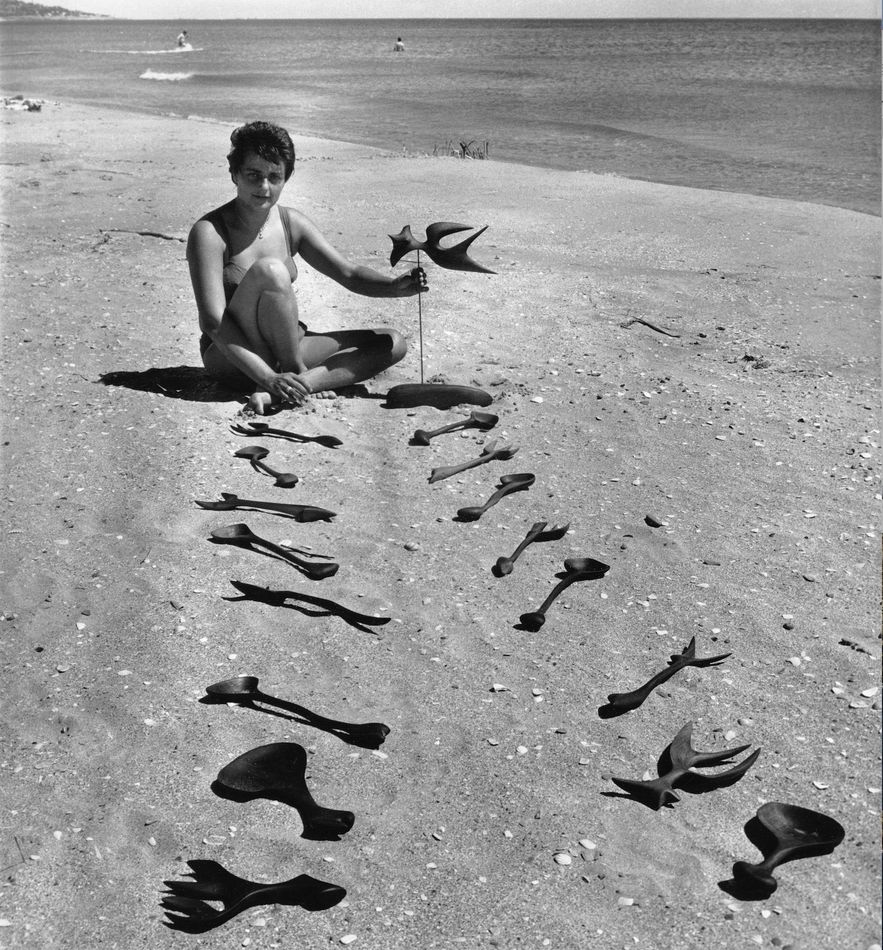

Valentine Schlegel on the beach. Metal sculpture and its wooden cutlery. Sète, photograph by Agnès Varda, 1958.

/ © Estate of Agnès Varda – Agnès Varda Fund deposited at the Institute for Photography Courtesy Galerie Nathalie Obadia © ADAGP, Paris, 2023

Behind the scenes of the main courtyard of the Popes’ Palace, Valentine meets Michel Bouquet, Sylvia Montfort or Catherine Sellers, but also Jeanne Moreau, who is starting out, and Gérard Philipe, already crowned with success. It was the latter who commissioned one of his first large white staff fireplaces that would sign his fame. These “living sculptures” with clean lines and immaculate whiteness, which she made from the end of the 1950s, invaded the domestic space, changing, according to her imagination, into shelves, consoles or benches. His creative process associates the human with the beautiful and the utilitarian: first soaking up the spirit of the habitat and that of the sponsors, before making a first clay model on a scale of 1/10 , then to shape a second one, more solid, out of plaster. Most often in a team, until – a rare thing – co-signing his works, from 1975, with Frédéric Sichel-Dulong, his main assistant and former student in the “modeling workshop for under 15s” that Valentine Schlegel founded at the Museum of Decorative Arts in Paris in 1958 and which she animated for almost thirty years.

Plaster fireplace models, 1/10th scale.

/ © LD

In this work, often collective, Valentine Schlegel never loses sight of the art of everyday living: “My sculptures seek utilitarian needs. Here, like magnets, attracted by their rightful place, they suspected the necessities for to intervene.” For the woman who describes herself as an “artist-craftswoman”, the art of living and art in general cannot be dissociated. “She never wanted to choose between popular arts and fine arts, not conceiving the beautiful without the useful and vice versa”, point out the curators. It’s because on each piece the shadow of the free woman hovers, both solitary and surrounded, who didn’t care to “do work”. After rue Vavin, she invested the studio of Agnès Varda, rue Daguerre, before settling in a house-workshop at 25, rue Bezout, in the 14th arrondissement, which she shared openly, from 1975, with Yvonne Brunhammer, Curator of Decorative Arts. That year, Yvonne wrote the catalog for her companion’s first monographic exhibition at the Galerie la Demeure. They will cohabit rue Bezout until their disappearance, three months apart, in 2021.

In the meantime, the house of Dior put the chimneys of Valentine Schlegel in the spotlight in its 2014 parade, and, more recently, the visual artist Hélène Bertin, originally from Cucuron, in the Luberon, took them as a subject of plastic research. The artist-craftswoman from Sète seemed, for her part, to have, modestly, programmed her posterity: “I will not always be there, but visitors will spend a moment like one goes to dip their feet in the water or read against a tree. My sculptures will be there to welcome them.”