Nikos Aliagas grew up with the image of Greece at the ruins of Missolonghi. The portfolio of his father Andreas concealed throughout his life a reproduction of the allegorical painting by Delacroix, a sort of sesame for this Greek immigrant, originally from the city besieged by the Turks in 1826, when he arrived in Paris in 1964 without speaking a French word. Fifteen years later, Andreas gives an Instamatic Kodak to his 11-year-old son Nikos, who has never let go of the little black box ever since. Today, at the age of 54, the former Franco-Greek image reporter turned TV star presenter keeps thousands of prints at home and exhibits – more and more in broad daylight over the years – his work. black and white shadow. This summer, he is presenting at the abbey of Jumièges, in the adjacent abbey dwelling, ruins with vertiginous gaps towards the sky, The Spleen of Ulyssesa free exploration of the myth of Homer, and publishes in parallel a book with the eponymous title (La Martinière editions).

“These images are the result of several years of travels and quests, a correspondence book that is both imaginary and real. The traveller’s nostalgia does not capitulate, it suggests a break while fleeing from the pose. The Spleen of Ulysses is a silent song, you don’t need to know the language to understand it”, underlines Nikos Aliagas, whose sixty photographs dialogue here with the medieval pieces of the lapidary collection of the abbey. And that often matches, as for this representation of ‘a pope from Missolonghi carrying a chalice, facing the Enervés de Jumièges, two recumbent stone figures (the sons of Clovis according to legend) whose hamstrings were severed to punish them for having tried to seize the paternal power and who, having entered into religion, were at the origin of the creation of the monastery. The hanging was done with the complicity of Sandra Prédine-Ballerie, director of culture and heritage of Seine-Maritime, of Benjamin Lesobre, responsible for the development of the site.

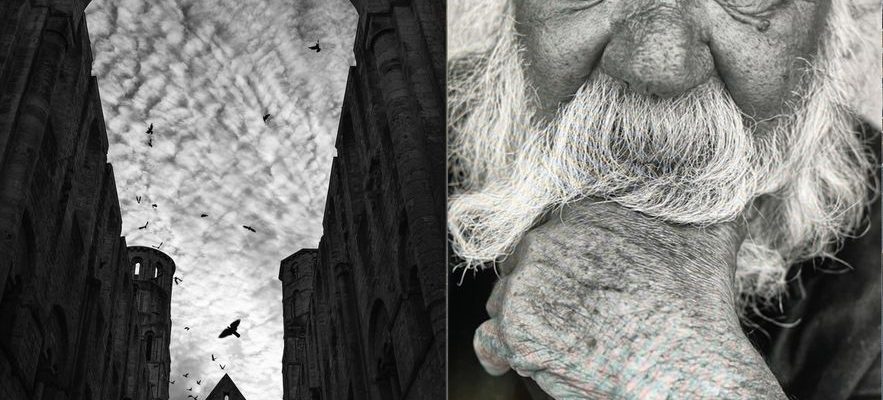

“The nave” (Abbaye, Jumièges), 2022. Right: “In the eyes of Panakias” (Stamna), 2017.

/ © Nikos Aliagas

“I live between two worlds”

The red thread of Nikos Aliagas’ photographic work is nostalgia – nostos in Greek – which constitutes “the vault of the whole Odyssey” in his eyes: “This Homeric term nostos, still used in Greece, expresses a form of return associated with a lack. It touches me, I who inherited my father’s exile and constantly live between two worlds: the West and the East, the visible and the invisible – behind the camera then in front. I find it in people’s eyes, everywhere, in the heart of the Costa Rican jungle, at a fisherman’s house in Greece or Morocco, and even there very close”, he points out, evoking this man perched head in hands on a mooring cock in front of a boat with a predestined name, Odysseuswhom he surprised on the banks of the Seine, at Rouen.

“The impossible return” (Rouen), 2022.

/ © Nikos Aliagas

“These encounters overwhelm me, they give me a feeling of brotherhood.” The photographer (witness more than artist, he says) does not seek the picturesque but the link: “These people, what do they have to say to me? It’s up to me to find a correspondence, a resonance, without sometimes achieve it.” From the first visual shock received in adolescence when discovering Los Olvidados of Buñuel, Nikos Aliagas retains a fascination for the grain of black and white, that of “cinematic photography at the service of a strong dramaturgy”. Later, the empathy of his lens was recognized in the work of contemporary photographers, although older, such as the Greek Vassilis Artikos, the Czech Josef Koudelka and the Franco-Brazilian Sebastiao Salgado, all focused on the human figure, its torments, its unspoken. The corpus of Aliagas brought together in Jumièges testifies to this sensitivity as much as to this desire for otherness.