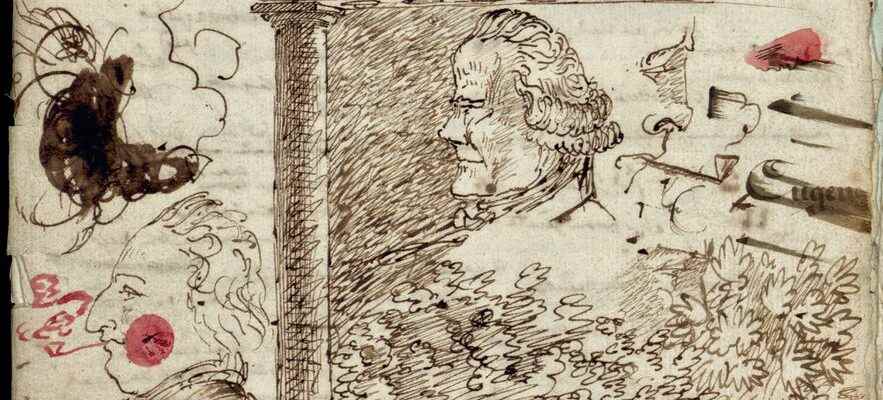

Who has never, on the sidelines of their school notebooks, scribbled during endless hours of class? Not the pupil Delacroix Eugène, in any case. At the Lycée imperial, in the years 1811-1815, the future painter sprinkled his Latin versions or his Italian compositions with caricatural profiles, figures of soldiers, men with pipes whose smoke dissipated in calligraphic lines, which he sign Il signor della croce, il buon ragazzo (mister of the cross, the good boy). Two centuries earlier, the future Louis XIII, aged 3 to 8, also gave pencils to fortune sheets, preciously preserved by the court doctor Jean Héroard, which were among the rare children’s drawings of time have come down to us.

These early productions are exhibited today, alongside 150 works, at the Beaux-Arts in Paris, which, in partnership with the Villa Medici in Rome and with the support of the Center Pompidou, highlights one of the most repressed and least controlled among artists: scribbling (scarabocchio in OV). All have devoted themselves to it, surreptitiously or in broad daylight, from the repetitive “grotesque” heads that dot the margins of Leonardo da Vinci’s scientific manuscripts, to the North African Sketchbooks by Cy Twombly and the urban paintings rich in graphic signs by Jean-Michel Basquiat. The curators of this fascinating and scholarly exhibition, Francesca Alberti, director of the art history department at the Villa Medici, and Diane Bodart, professor of the same discipline at Columbia University, have evacuated any chronology in favor of surprising placed in perspective.

Eugène Delacroix, “Class notebook”, 1815.

/ © INHA

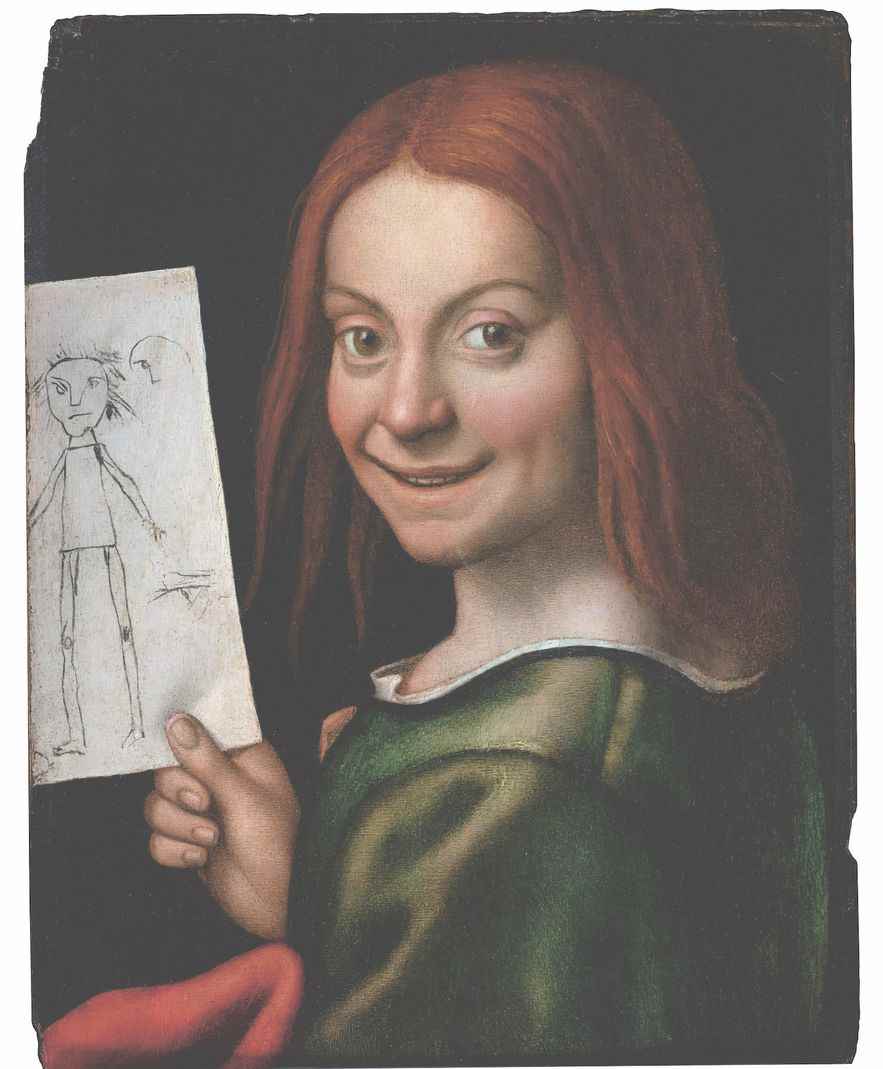

Presented exclusively, a painting by Veronese Giovanni Francesco Caroto (1480-1555), who owes his surname to his carrot hair, catches the eye. This Child showing a drawing double trouble. What is behind the sarcastic kid (the artist himself?) and the drawing, with timeless rough lines, which could be from the hand of any toddler of our contemporary era. At the end of the 16th century, the Carracci, led by Hannibal, popularized “the importance of graphic entertainment” in their workshop. Parts of the body are sketched there quickly, in a context of amusement and without hierarchy, until giving birth to the caricature resulting from the grotesques of Leonardo. Later, in a sketch attached to the Madonna with canopy, Raphael, star of the Italian High Renaissance, compulsively duplicates the figure of the baby Jesus deployed in a rainbow in ever more attenuated lines. The painter infinitely renews the embrace between the Virgin and the child, “one of the archetypal figures of his creative imagination” that we find in his Complete work published this fall 2023 by Taschen editions (see box below).

Giovanni Francesco Caroto, “Portrait of a child showing a drawing”, 1515-1520.

/ © Archivio Fotografico dei Musei Civici, Verona (Gardaphoto, Salò)

A century later, Gian Lorenzo Bernini, known as Bernin, played the precursors of caricature with his ritratti caricati (charged portraits) which ridicule those portrayed, but also the sketch itself by reducing it to the simplest line. “The existence of several versions of the same drawing shows the rapid success met by these new entertainments. But it is also the expression of a reverse virtuosism of the artist capable of repeating again and again the spontaneity of his gesture. biting”, underline the commissioners. Water has since flowed under the bridges, but the gesture has endured. At Brassaï, for example. In the 1930s, the photographer blackened his graffiti notebooks, where he scrutinizes the capital of working-class neighborhoods that he places in resonance with the prehistoric designs of ancient Egyptian and Mesopotamian civilizations. He called it “the bastard art of the disreputable streets”.

Scribble/Scarabocchio at the Beaux-Arts, Paris VIe, until April 30.

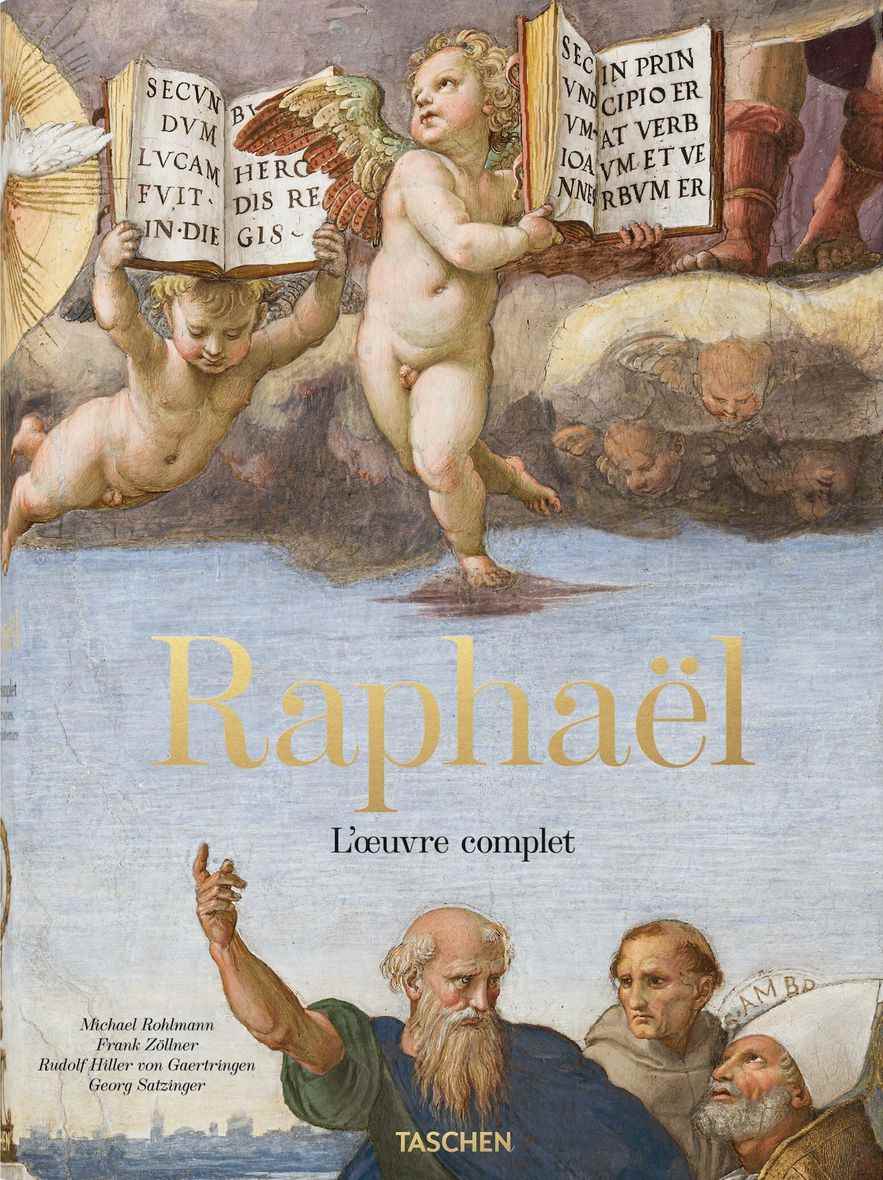

The back-to-school 2023 art book: Raphael, The Complete Work

XXL Edition, €150.

/ © Taschen

It’s an XXL book as Taschen has the secret. His challenge, brilliantly met: bring together all of Raphaël’s works, from his paintings to his architectural creations, including his cycles of frescoes and his tapestries. The work, which weighs its weight (nearly 6 kilos!) and has 720 pages, is the most substantial ever published on the leading artist of the Italian High Renaissance for which he formed, with Leonardo da Vinci and Michelangelo, the dominant pictorial trio of the period. Like Leonardo, his eldest, Raffaello Sanzio (1483-1520), known as Raphael in our latitudes, is inhabited by an incessant quest to learn and renew himself, hailed during his lifetime for his modernity whose audacity finds its apotheosis in the decoration. His mature works, produced in Rome, including the sublime frescoes of the Vatican, establish his posterity.

From feminine sensuality to ancient myths, from portraits to history paintings and biblical scenes, the artist expressed himself in all mediums, showing an unlimited imagination and interacting with the spheres of power of the time, such as analyzes the work. Today, he remains the one who “transformed his favorite theme, the visionary experience of divine grace, into a visible pictorial reality”. L.Da