For more than thirty-five years, Djamel Tatah, 63 years old today, has been deploying on the canvas a life-size theater of ghostly silhouettes, devoid of narrative context. Alone, in tandem or duplicated to infinity, his characters exhale an isolation that does not speak its name or its era, but inevitably sends back to the viewer a feeling of incommunicability specific to our contemporary societies.

The childhood of the artist, who was born and raised in the Gier valley (Loire) where his parents had settled in the mid-1950s after leaving their native Kabylie, was rocked by Arab-Andalusian sounds. of the chaâbi his father loved. But it’s the music of Marvin Gaye, and more precisely the album What’s going on released in 1971, discovered as a teenager, which, he says, forged his artistic identity: “He helped me build all the themes that run through my painting: war, injustice, loneliness, the quest of spirituality.”

Djamel Tatah, “Untitled”, 2019 (cuts engraved and painted on varia fireproof canvas).

/ © Frédéric Jaulmes © Adagp, Paris, 2022

The Fabre museum in Montpellier, the city where Djamel Tatah took up residence in 2019, is devoting an important monograph to him until April 16. The artist himself orchestrated the hanging of some forty paintings there, mostly large formats, alongside curators Michel Hilaire and Maud Marron-Wojewodzki. Here, the works explore different periods of his creation from a thematic angle, while in Paris, the Poggi gallery presents in parallel, and until February 24, a dozen recent works, most of them dated 2022. Thought by the painter in the continuity of the Montpellier exhibition, the Parisian scenography sees placed at the beginning and at the end of the route very colorful paintings and in the center of the white works to “naturally generate a movement in space”.

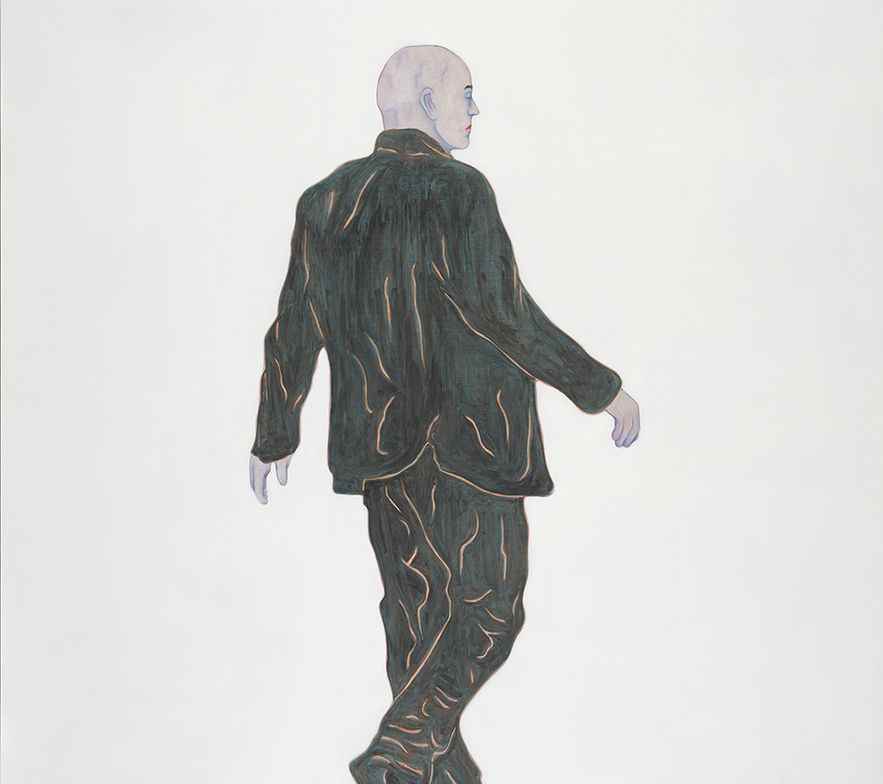

Djamel Tatah, “Untitled”, 2022.

/ © Courtesy Poggi Gallery

“Silent Painting”

Montpellier, The Theater of Silence thus announces the color, so to speak, of this “silent painting” which places the human figure at the heart of monochrome flat areas. Ageless bodies, singular postures, which Tatah first collects in a photographic repertoire made up of images taken from his relatives, taken from current events gleaned from the media or drawn from the history of art, before rework them digitally then project them on the canvas to paint them with oil and wax.

“I am looking for the abstract expression of a representation of man, with a desire for stripping”, claims the former student at the Saint-Etienne school of fine arts, who has never stopped nurturing its inspiration in the light of the works of the masters of the past preserved in tirelessly surveyed museums: from Saint Francis of Assisi from Zurbaran to Nave Nave Mahana of Gauguin, mirror paintings by Michelangelo Pistoletto with photographic plates by Eadweard James Muybridge, frescoes by Fra Angelico with Outrenoirs by Soulages, of which the Musée Fabre has the first version dated 1979.

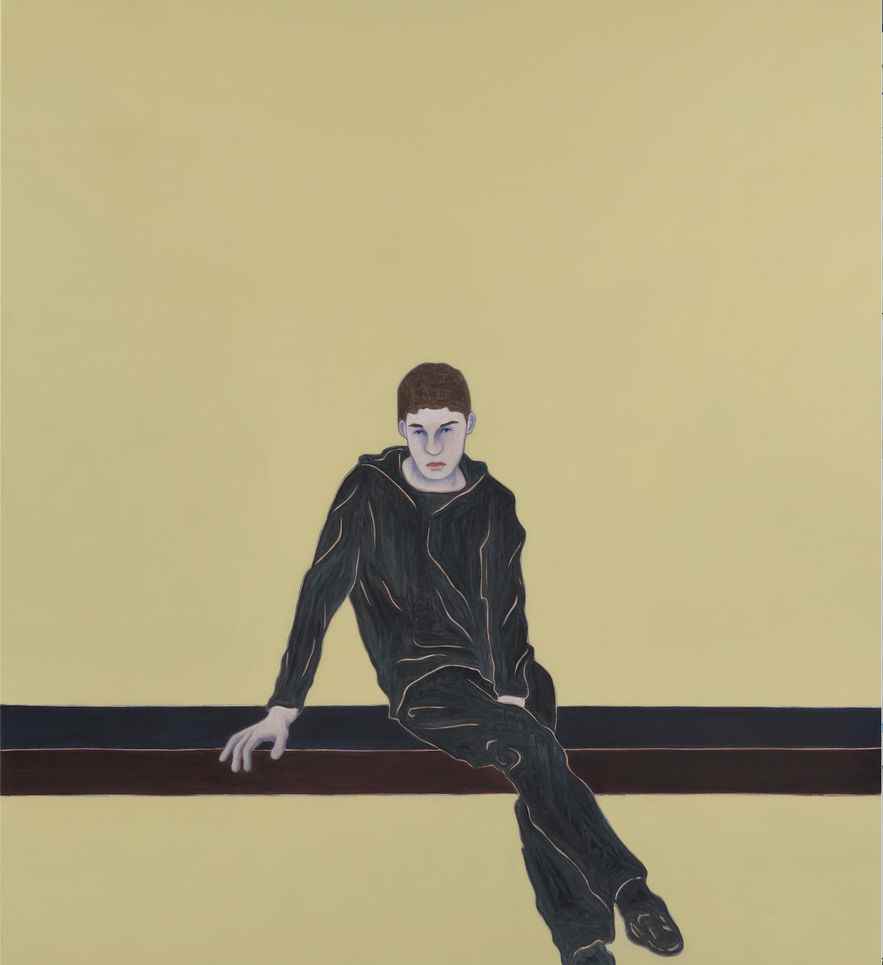

Djamel Tatah, “Untitled”, 2016.

/ © Jean-Louis Losi © Adagp, Paris, 2022

Where do these evanescent figures with tight lips and lowered eyes come from? “The psychological dimension of the portrait does not interest me […] I leave my way of representing the human being open, therefore my figures are anonymous… They can be everyone”, confides Djamel Tatah in an interview with Michel Hilaire. To the art historian Mouna Mekoar, author of the presentation text of the exhibition at the Poggi gallery, he evokes the representation of violence in our world, to which he opposes the questions that haunt his work: “How to speak of mourning? How to talk about the intimate but also collective tragedy? How to move from I to We?

Djamel Tatah, “The Women of Algiers”, 1996.

/ © Jean de Calan © Adagp, Paris, 2022

His Women of Algiers, one of his rare titled paintings, obviously echo Delacroix, even if Djamel Tatah paints them and duplicates them twenty times in homage to women in a second version, from 1996, in resonance with the tragic events in Algeria of the time. A few years later, the advent of the Internet upset the artist’s “graceful and indomitable” pictorial practice: “Questioning the world does not mean describing it literally or showing its horrors without any filter. Painting can transpire otherwise what it represents. What is important is to find a form, a way of talking about these things.”