Lula da Silva had announced it the day after his election, on October 30, 2022: “Brazil is back!” On the international scene, the diplomatic offensive of the Brazilian president, who sees himself as the champion of the “Global South” [NDLR : terme désignant les puissances dites émergentes] is not, however, conclusive.

Unconvincing in his attempts to mediate between kyiv and Moscow, because he was criticized for his pro-Russian positions, Lula had, at the beginning of the year, caused an outcry by comparing the Israeli operation in Gaza to the Holocaust. The man who defines himself as the leader of the South American left has strangely shown little emotion about the tragedy playing out on his borders. Thirty demonstrators killed, 2,000 citizens imprisoned, including dozens of minors, the repression that has descended on Venezuela after the fraudulent re-election of President Nicolas Maduro on July 28, has only provoked weak condemnations from the Brazilian leader. “Maduro’s behavior leaves something to be desired,” he declared. And what about the flight to Spain of Edmundo Gonzalez Urrutia, the opposition candidate, after the arrest warrant issued against him in early September? “Very worrying,” his diplomatic advisor Celso Amorim simply reacted.

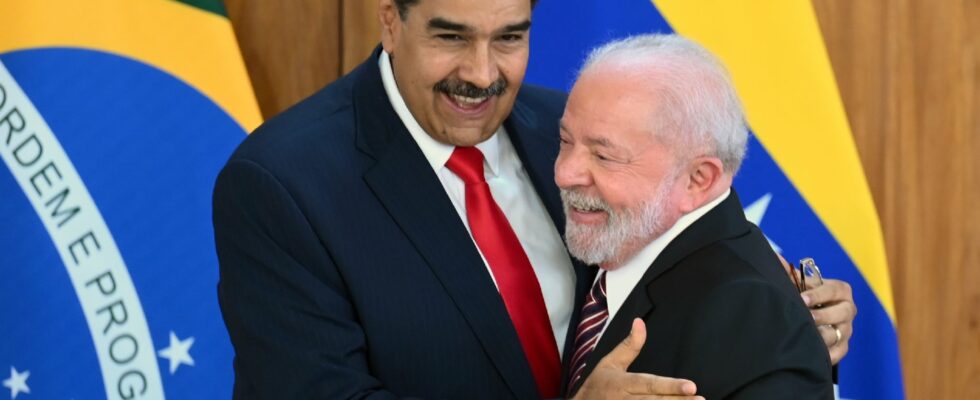

In Brasilia, the observation is bitter: Lula da Silva seems to have no hold on the strongman of Caracas. “I spoke personally to Maduro before the election,” confided the Brazilian head of state. “I told him that it would be precisely the transparency of the electoral process and the legitimacy of the result that would allow us to fight for the lifting of Western economic sanctions against Venezuela.” Failed. For Lula, who had bet on ideological convergence with Hugo Chavez’s successor and political heir, the failure is obvious – and all the more damaging since the Venezuelan crisis represents a major diplomatic test for him.

Lula’s Ambiguity

The Brazilian leader still wants to believe in it: Maduro, whose current term does not end until January, “still has four months ahead of him,” he recalls. Europe and the United States have indeed relied on Lula to find a negotiated outcome. But Latin America has changed a lot since the first presidency of the leader of the Brazilian left, twenty years ago. “Lula remains an important voice on the continent, but reaching regional consensus is now more difficult,” observes Denilde Holzhacker, professor of international relations at ESPM University in Sao Paulo. However, the Venezuelan question calls into question Brazilian leadership in the region. “Several countries, led by Argentina, have shifted to the right and criticize Lula’s ambiguity towards Maduro,” she continues. “Even the Latin left is divided!” Like the President of Chile Gabriel Boric, who embodies a new left-wing leadership and has condemned electoral fraud. Which Lula, himself, is reluctant to do.

Forced to restrain himself because of his ideological proximity – but also because he does not despair of attempting mediation – Lula has not recognized Maduro’s “victory”, while dismissing the two adversaries back to back. “Without proof, I will not recognize the victory of either one,” he says… without believing it himself. The electoral reports have still not been made public by the National Electoral Council. As for the ballots counting the candidates’ scores by polling station, they “would no longer prove anything,” he is said to have said privately. More than a month after the election, the regime would have had plenty of time to falsify them.

“Logically, Brazil should change its tune and align itself with the Venezuelan opposition,” notes Denilde Holzhacker. With all the risks that this entails with regard to Brazilian public opinion. How can we disavow a Maduro who still has support on the left in Brazil? How can we accredit accusations of electoral fraud without fueling the conspiracy theories of the far right? Lula has not forgotten that in 2022 his predecessor Jair Bolsonaro accused him of having “stolen” his victory. “Brazil has put itself in a hopeless situation,” laments Hussein Kalout, a researcher at Harvard University and former diplomatic advisor to the Brazilian presidency. “We should have been much firmer with Maduro, and this for a long time, because violations of the electoral process are not new.”

Let us judge for ourselves. In January 2024, the Venezuelan leader of the United Platform of the Opposition, Maria Corina Machado, the regime’s bête noire, was prevented by the courts from contesting the election. Then it was the turn of her replacement, Corina Yoris. In the agreement he had signed with his opposition on October 17, 2023, Maduro had nevertheless committed to holding free elections, in exchange for an easing of American economic sanctions. Still believing in their special relationship, Lula had guaranteed his word. And had received her in Brasilia on May 29, 2023, putting an end to the travel ban that Bolsonaro had imposed on him. “Until the end, Lula wanted to believe that Maduro could win without fraud,” points out Hussein Kalout. “His strategists underestimated the organizational capacity of the Venezuelan opposition and the extent of popular discontent. Everything happened as if Lula’s Brazil was accommodating a Maduro who was certainly authoritarian, but a geopolitical ally within the Global South,” the hobbyhorse of Lula’s diplomacy.

Lula has little leverage over Maduro

Cornered, the Brazilian president cannot even push for the organization of a new election – a fixed idea for him. First, because Nicolas Maduro does not want one – and neither does his opposition. Second, because Russia and China – two major competitors of Brazil in Venezuela – have already recognized his victory. Moscow supplies its weapons to Caracas, while Beijing buys its oil, subject to American sanctions. Compared to it, Brazil is no match. Putting Maduro under pressure would probably have only one effect: consummate Maduro’s break with Lula… who cannot afford it. “Economically, Brazil depends more on Venezuela, which supplies electricity to the Brazilian state of Roraima, than the opposite,” specifies Hussein Kalout. The only lever at Lula’s disposal is that “Maduro needs the recognition of Brazil, the largest democracy in Latin America,” continues the researcher.

Is this enough? Not sure, especially since the hardening of the regime makes it more difficult to get out of the crisis. Clearly, the “bossa nova diplomacy”, as Brazilian foreign policy is nicknamed, continues to hit a series of false notes.

.