Among insiders, we call him “the American”. Or the “War”. An extremely rare version of the Michelin Guide, which every fan of the red book with stars must own… if they have the means. On June 6, at the Clermont-Ferrand auction house, stronghold of the tire manufacturer, a copy in good used condition will be auctioned on the occasion of the 80th anniversary of the D-Day landings. Estimate: between 5,000 and 7,000 euros. “It’s the holy grail of every enthusiast,” confides Me Bernard Vassy. Since his first sales of Michelin-branded objects, twenty-five years ago, this auctioneer has only sold… seven.

Claude de Bruycker, a luminary in the small club of collectors, owns “a few”. Discreet about the exact number of his treasures, this Belgian based in Ghent is on the other hand inexhaustible about their rarity. “The first Michelin guide, dated 1900, which is also very sought after, was published in 30,000 copies. But the “American” is really not common. In my opinion, it was only made ‘to a few thousand units, the vast majority of which has certainly disappeared. I am proud to have it: in my library, I show it from the front, and not on the edge.’

At the Michelin Adventure, the group’s museum located north of the Auvergne capital, a specimen also sits in a window. Marie-Claire Demain-Frackowiak welcomes us to the reserves. It is here, in a fireproof room where thousands of maps and guides are stored, that the other original in the company’s possession is kept in an archive box. “You can handle it… with care,” says the Michelin historical heritage manager, taking out the relic, wrapped in tissue paper.

A true copy, except the cover

Cabourg, Cabrerets, Cadenet, Cadeuil… Throughout the 1,100 yellowed pages, French towns and villages parade in alphabetical order, with their restaurants and hotels duly commented on, in the flowery style of the time: “Certain favored regions – the Lyonnais for example – are traditionally regions of good food No matter where the motorist stops, he is almost sure to have a good meal. The stars then indicate to him “the best among. the good ones.” Other regions are less well endowed: a meal taken haphazardly risks being mediocre.” A carbon copy of a classic Michelin. With one difference: the sand-colored cover, and not red, which contains the two mentions that give it so much value. For official use only And Reproduced by Military Intelligence Division, War Department, Washington DC A piece of World War II history, between pear and cheese.

The “American” guide entered the legend on the morning of June 6, 1944, when the men of General Bradley, the commander in chief of the 1st US Army, set foot on the Normandy beaches of Omaha Beach and Utah Beach . Before the start of Operation “Overlord”, each American officer was given a facsimile of the last updated version of the Michelin, that of 1939 – its manufacture, boulevard Pereire, in Paris, having ceased in 1940, due to the Occupation.

The objective, as one might imagine, was not gastronomic but… cartographic. Rich in 500 city plans, detailed street by street, and a host of indications on the roads, railways, bridges and other petrol stations in France, this pavement weighing 700 grams and 7 centimeters thick was to allow chefs Ranger battalions and infantry divisions to find their way in unknown territory. An early GPS, simple, precise, with a nomenclature perfectly suited to non-French speakers, and all the more useful since road signs, destroyed or removed by the Germans, were then missing in the country. Eighty years later, this is almost all we know about this unique guide.

A lot of riddles

Did the soldiers use it? The last copy sold at auction in Clermont-Ferrand suggests this: it was dog-eared and distorted in length, a sign that its owner kept it close at hand, in the pocket of his fatigues. In addition, some specimens still in circulation bear the handwritten name of their owners. Who therefore seemed to hold on to it. And otherwise ? Marie-Claire Demain-Frackowiak admits her frustration: “Every time I watch a documentary on the Allied offensive, I scrutinize the slightest image to try to spot one… I have never seen one.” Nothing in the veterans’ stories either. Nor in the history books. “Some time ago I showed the reproduction of this guide to Professor Olivier Wieviorka, the great specialist of the period. He did not know it,” sighs the Michelin expert.

Second enigma: what did the GIs do with it at the end of the war? “Between the water, mud and dust, the paper in the guides was put to the test. In my opinion, many of them got rid of it,” judges Claude de Bruycker. Less categorical, Me Bernard Vassy thinks that “certain officers had to return with it to the United States: it was one of the rare civilian memories of their commitment to freedom.”

The key role of Commander Moutet

Another mystery has until now surrounded “the American”: its genesis. How did the 1939 guide reach military intelligence on the other side of the Atlantic? By clandestine routes from the Auvergne factory? Or by a tourist who came before the war to visit France and who brought it back in his suitcases? No one, not even at Michelin, ever knew anything about it. Author of numerous works on Bibendum derivative products, Pierre-Gabriel Gonzalez was also lost in conjectures for years. Until his phone vibrated… three weeks ago. “A collector sent me a photo of an old English press clipping: it’s an incredible scoop!” enthuses this former journalist from The mountain, became a consultant for the auctions organized in Clermont-Ferrand.

“Gourmet guide that paved the way to victory” (“The gastronomic guide which led to victory”). Over two columns, the article in question recounts in great detail how Commander Gustave Moutet, finding the 1939 Michelin guide much more precise than his state maps- major, relied on him to facilitate, in May 1940, the evacuation of British and Canadian troops surrounded by German panzers during the “Battle of Dunkirk”. former socialist minister Marius Moutet – one of the 80 parliamentarians who refused full powers to Pétain – then took the boat for London on June 17 and joined the Free French Forces. Introduced into the military circles around General de Gaulle, In 1943 he entrusted his red guide to the American command, which then decided to reprint it.

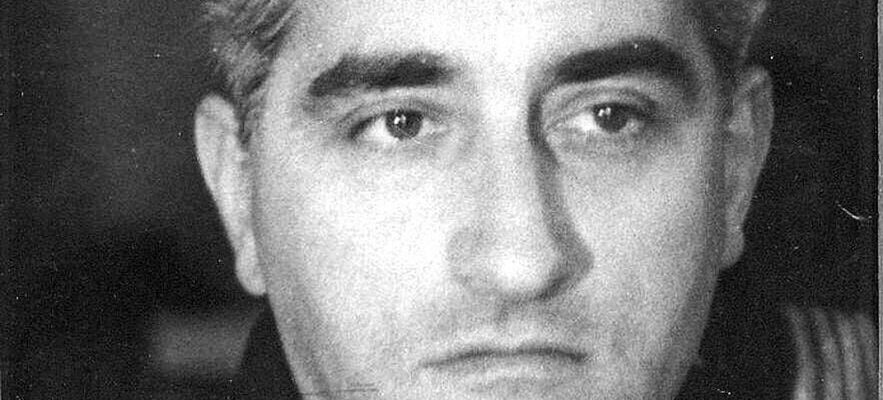

Commander Gustave Moutet.

© / DR/©Anne-Elisabeth Moutet.

Four weeks after D-Day, Gustave Moutet returned to France as liaison officer to General Patton. After the Liberation, he embraced a career as a senior civil servant, in the wake of his father, who once again became Minister of Overseas Affairs. His black and white photo, as well as that of the “American” guide, accompanies the article. “Great roads, good restaurants, for the US troops,” reads the caption. “A story like this cannot be invented”, wants to believe Pierre-Gabriel Gonzalez.

The author of the article, the commander’s own daughter, Anne-Elisabeth Moutet, confirms this to L’Express: “My father had bought the 1939 Michelin guide in anticipation of his vacation in the South of France. He loved driving and walking around a lot When he was mobilized, he went to the front with his copy under his arm. He told me the whole story afterwards. In 1984, I was a correspondent in Paris for the. Sunday Times. I proposed this subject to my bosses, on the occasion of the 40th anniversary of the Landings. I didn’t think he would reappear forty years later! In any case, I still have at home the “American” guide with which my father returned to France.” A family saga which finally reveals the underside of the cards.

.