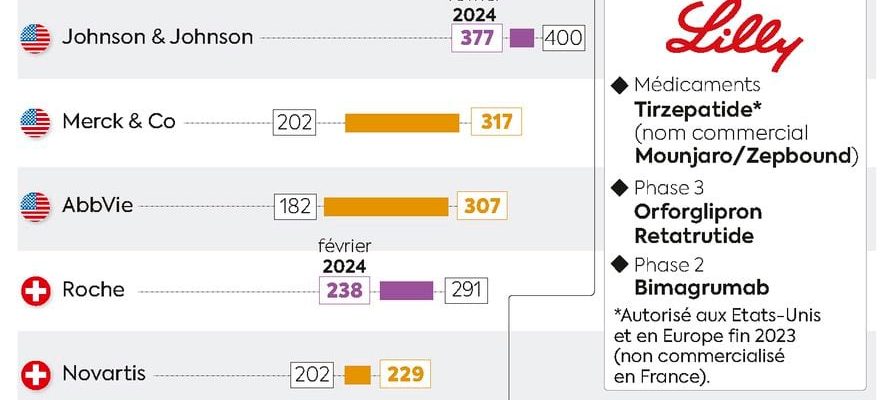

In the left corner of the ring, the American Eli Lilly, 148 years old and a market capitalization that just exceeded 700 billion dollars. In the right corner, the Dane Novo Nordisk, 101 years old and a stock market value that reaches $536 billion – more than the gross domestic product of his own country! Three years ago, these two pharmaceutical laboratories were still lightweights, with their respective 158 and 162 billion. Since then, they have become the undisputed champions of the global pharmaceutical industry. The giants Merck, AbbVie, Roche, AstraZeneca, Novartis and even the former number 1 Johnson & Johnson no longer compete in the same category.

What happened ? The GLP-1 revolution, a hormone that our intestines naturally secrete and which can be imitated by drugs called “GLP-1 agonists”, which activate the receptors for this hormone. The first treatment of its kind, Ozempic, was invented by Novo with the aim of treating type 2 diabetes and was authorized in the United States by the FDA, the drug watchdog, in 2017. But very quickly, the Danish laboratory notices that his diabetic clients lose weight, and not just a little, with limited side effects (nausea, vomiting, even intestinal obstruction). The Graal. Ozempic proves to be an effective appetite suppressant. Or rather “a medicine which causes a feeling of satiety”, since since the scandals of amphetamine and similar medicines like Mediator, the term “appetite suppressant” is equivalent to that of “Voldemort”, the one whose name we do not pronounce. , in Harry Potter.

In red: strong growth in market capitalization from 2020 to 2024 In yellow: moderate progression In purple: regression

© / Art Press

Future best-selling drugs in the world?

The news spread like wildfire, demand exploded, in particular because of its misuse among non-diabetic people who want to lose weight, to the point of causing stock shortages. Little wonder: more than a billion people on Earth are obese, including 650 million adults, 340 million adolescents and 39 million children. France is not spared, with 17% of adults obese, according to an Inserm survey. A “global epidemic”, points the World Health Organization, which reminds us that these figures have tripled since 1975 and are still increasing. By 2035, 25% of the world’s population could be obese.

Analysts at the Swiss bank UBS quickly made the calculations: GLP-1 agonists could become “the best-selling drugs in history”. Their colleagues at JP Morgan confirm : “This booming sector could generate up to 93 billion euros in annual revenue by 2030.” Dizzy. But not as much as the global annual cost of obesity, which could reach nearly 3,700 billion euros in 2035 – the equivalent of a new covid-19 pandemic every year -, according to estimates from the World Obesity Federationwhich takes into account health costs and work time lost due to illness and premature death.

3789-COVER-OBESITY-LAUNCH

© / ART PRESS

To meet this massive demand, Novo then launched Wegovy, which shares the same chemical formula and process as Ozempic – a weekly injection pen – but differs in a higher dosage and an indication aimed solely at obesity. Tests suggest it provides 15% weight loss. The FDA gives its authorization in June 2021, a first since 2014 for an anti-obesity drug. Success is immediate. In its latest activity reportNovo indicates that its sales of Ozempic and Wegovy reached 4.2 and 13 billion euros respectively in 2023.

Eli Lilly, who is seriously behind, loses the first round. But there is no question for this diabetes specialist and historic competitor of Novo Nordisk to let himself be further ahead. Its antidiabetic drug Mounjaro, if not approved by the FDA until 2022, is an improvement over Wegovy. It activates the GLP 1 receptors but also those of the GIP hormone, whose functions are complementary. The American hits the nail on the head: Mounjaro allows for greater weight loss, of around 20%. The laboratory is subsequently developing its own derivative for obesity, Zepbound, which obtains marketing authorization in the United States in November 2023, then in December 2023 for the European market (where it keeps the name Mounjaro) . Success is still there. In 2023, Lilly will sell $5.1 billion worth of Mounjaro and €175 million worth of Zepbound (in just one month!).

The scientific battle: more drugs, more start-ups

Since then, the two champions have gone blow for blow in the scientific ring. It doesn’t matter if neither can satisfy global demand, each wants to get the biggest piece of the pie. Novo Nordisk has launched the development of five new anti-obesity drugs. Among them, Cagrisema, a weekly injection, must compete with Zepbound/Mounjaro by offering greater effectiveness thanks to the combination of GLP-1 agonists and amylin, another hormone secreted by pancreatic cells. The Dane is also working on drugs that are easier to use, such as oral solutions (Oral semaglutide) which could appeal to people with needle phobia, but above all eliminate the tedious processes of producing sterile needles.

Lilly has already launched six treatments, including Orforglipron, its own oral GLP-1 agonist solution, but also Retatrutide, a “triple agonist” injection targeting the GLP-1, GIPR and glucagon receptors, which aims to be even more effective than Cagrisema. If the laboratories do not display full transparency regarding their expenses, this war is probably very costly. According to several studies, the price of research and development of a new drug varies from a few hundred million to 4 billion euros.

And this is probably just the beginning. The two companies are also exploring the possible uses of GLP-1 agonists in other pathologies, each seeking to expand its market. Last summer, Novo published a study indicating that Wegovy reduces the cardiovascular risks of obese people by 20%, which made him earn 50 billion euros of market capitalization in one day. Recent studies suggest that this agonist could also act on neurological diseases. “Lilly and Novo are working on Alzheimer’s, which is hardly surprising since GLP-1 has a neuroprotective effect,” indicates Olivier Soula, director of Adocia, a biotech company specializing in diabetes. “We are exploring this application,” confirms Etienne Tichit, general manager of Novo France. “The Evoke study, which is following 3,700 Alzheimer’s patients, has not yet delivered its results, but we hope for anti-inflammatory activity.” Their Flow study focuses on renal inflammation.

The Danish laboratory is also preparing to spend 1 billion euros to acquire Inversago, at the forefront of a drug blocking the cannabinoid CB1 receptor which plays a role in regulating appetite and could be effective in diabetic kidney disease. Not to be outdone, Lilly has already swallowed up the company Versanis for 1.8 billion euros, which is developing an antibody aimed at reducing fat while strengthening muscle mass. A major issue, GLP-1 agonists being accused of making patients lose too much muscle.

The battle of production: always more, always faster

The match is also industrial. “Whoever is the first to satisfy the largest possible demand will be best placed in the battle,” notes one observer. In February 2024, Novo announced that it wanted to buy Catalent for 15.3 billion euros. This American company has more than fifty pharmaceutical factories around the world, an impressive strike force. “We had already invested 10 billion euros in 2023 in order to develop our production sites, including that in Chartres (which received 2.3 billion)”, adds Etienne Tichit, who foresees a “rise in production in from 2026-2028″.

Lilly, for its part, has spent “more than 10 billion euros” in its factories over the last three years, including 2.3 billion for its Alzey site, in Germany. “And we have injected 160 million euros into our factory in Fegersheim, in Alsace, in order to launch a high-speed production line which will accelerate our manufacturing of injector pens for Mounjaro”, counterattacks Marcel Lechanteur, president and general manager of Lilly in France.

The lobbying battle: 457,000 meals paid to doctors

American media have also reported expenses that laboratories boast less about. According to the specialist site Statnews, Novo thus offered more than 457,000 meals to thousands of doctors in 2023 in order to promote its drugs, in particular Ozempic. Nearly 12,000 prescribers were offered a dozen meals during the year, while around a hundred devoured more than 50. All for 8.3 million euros. “Making doctors eat so that they can prescribe slimming pills is quite a concept… It is unfortunately a very common practice in the pharmaceutical industry,” recalls Etienne Nouguez, sociologist at the CNRS. Common, but exceptional at this level, especially since we must add the 2 million euros of travel offered to doctors to go to London, Paris, Orlando or Hawaii. Even Lilly bought “only” 184,000 meals (3.2 million euros).

The two laboratories are also fighting to come first in the markets of different European countries. In France, for example, everyone hopes to be the first to obtain reimbursement from Health Insurance for their weight-loss injections. And in many other countries, they try as much as possible to convince mutual societies or insurers to reimburse their products.

Pfizer, AstraZeneca, Amgen: competition in ambush

By controlling production sites and gaining a significant time advantage through their research, Novo and Lilly took a comfortable lead. But they will not be able to meet all the demand. The competition is therefore already in ambush. “In pharmacology, we call this a blue ocean: a new space with very little competition where it is possible to navigate without limits,” illustrates Olivier Soula. Dozens of companies have already taken the plunge, including Pfizer and AstraZeneca. 86 other GLP-1 agonist or similar drugs are under development, according to a Statnews analysis. All are banking on greater benefits, less marked side effects (including weight regain after treatment), or less constraint, like Amgen which is developing a monthly GLP-1 injection rather than weekly. Enough to give hope for useful treatments for hundreds of millions of patients.

Enough to hope for future treatments that are even more effective and useful to hundreds of millions, even billions of patients, but also to invite vigilance, as GLP-1 sometimes seems to be sold in all sauces. “It’s not a miracle drug!”, defends Etienne Tichit. This slogan is, according to him, the work of the media. “And faced with the promises of drugs supposed to save the world, we must always exercise extreme caution,” recalls Etienne Nouguez, smiling.

.